KEY POINTS

Acute pancreatitis is a frequent cause of gastrointestinal-related critical illness.

Most cases are caused by alcohol and gallstones; other etiologies include hypertriglyceridemia, post-ERCP pancreatitis, hypercalcemia, trauma, infections, and medications.

Two of the following three criteria establish the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis: sudden onset of characteristic abdominal pain; serum amylase and/or lipase above three times normal; pancreatic inflammation on imaging studies.

There are two types of acute pancreatitis—interstitial edematous and necrotizing. The former has pancreatic enlargement with diffuse pancreatic and peripancreatic inflammation. The latter has necrosis of pancreatic and/or peripancreatic tissue, in addition to inflammatory changes.

Early crystalloid administration in fluid-responsive patients is important in the management of acute pancreatitis.

Early enteral nutrition has been validated as an important component of the management of acute pancreatitis; avoiding enteral feeding and/or use of parenteral nutrition is not recommended.

There is no role for prophylactic antibiotics in the management of acute pancreatitis; however, broad spectrum antibiotics (eg, carbapenems) are indicated in the presence of documented or suspected pancreatitic infection.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is indicated in patients with acute gallstone pancreatitis with cholangitis and those with pancreatic duct disruption.

Endoscopic debridement is superior to open necrosectomy for the management of mature, walled-off fluid collections.

Acute pancreatitis is currently the most frequent gastrointestinal cause of hospital admissions in the United States with a total of 275,000 admissions in 20091 and approximately $2.2 billion in annual health care costs.2 The overall mortality among patients with acute pancreatitis is around 5%, but patients who develop severe acute pancreatitis have mortality rates as high as 15%3 and even higher when multiorgan failure is present. Appropriate intensive care management of these patients and a multi-disciplinary approach play a very important role in treatment of those patients who develop severe acute pancreatitis. In 2012, a revised version of the original Atlanta classification was published that focused on defining the severity of acute pancreatitis and classification of pancreatic and peripancreatic fluid collections.4

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Acute pancreatitis is believed to be triggered by an increase in the intraductal pressure or direct injury to acinar cells from metabolic or toxic stimuli which leads to breakdown of the junctional barrier between acinar cells and leakage of pancreatic fluid and enzymes into the interstitial space.5 Intrapancreatic activation of proteolytic enzymes leads to autophagy and autodigestion of acinar cells.6 Lysosomal enzymes such as cathepsin B initiate the activation of trypsinogen to trypsin which then leads to activation of more trypsin as well as other pancreatic enzymes including phospholipase, chymotrypsin, and elastase.7 The acinar tissue death leads to an intense systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) caused by the release of activated pancreatic enzymes and mediated by cytokines, immunocytes, and the complement system. Inflammatory cytokines (such as tumor necrosis factor) cause macrophages to migrate into tissues distant from the pancreas, including lungs and kidneys. Immunocytes attracted by cytokines released from macrophages release more cytokines, free radicals, and nitric oxide; the result is tissue destruction, fluid and electrolyte loss, hypotension, renal and pulmonary complications, late septic complications, and, in severe cases, multisystem organ failure (MSOF) and death.

ETIOLOGY

The two most common causes of pancreatitis in the United States are alcohol and gallstone pancreatitis, accounting for approximately 75% to 80% of the cases. Other common etiologies include hypertriglyceridemia, post-ERCP pancreatitis, hypercalcemia, trauma, infections, drug injury, anatomical variants such as pancreas divisum, and idiopathic pancreatitis (Table 108-1). Recently, multiple studies have shown smoking to be an independent risk factor for acute pancreatitis in a dose-dependent manner.8-10

Etiology of Acute Pancreatitis

| Toxic |

|

| Mechanical obstruction/duct damage |

|

| Metabolic |

|

| Immune-related |

|

| Drugs |

|

| Infections |

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

Patients who are critically ill are also at increased risk of developing pancreatitis due to ischemic injury.11 Hypoperfusion can play an important role in the progression of mild acute pancreatitis to severe, necrotizing pancreatitis in those cases where the initial insult was due to the more common etiologies in noncritical care setting.12

DIAGNOSIS AND ASSESSMENT OF SEVERITY

Most patients with acute pancreatitis present with sudden onset, severe, persistent epigastric, or right upper quadrant pain, with or without radiation to the back associated with nausea and vomiting.13,14 Physical examination findings vary according to the severity of the disease and range from mild epigastric tenderness to a diffusely tender abdomen. Presence of ecchymotic discoloration in the periumbilical region (Cullen sign) or along the flanks (Grey Turner sign) suggests retroperitoneal bleed.

Serum amylase and lipase are both elevated early in the course of acute pancreatitis (within 4-12 hours). Amylase has a shorter half-life of 10 hours and returns to normal within 3 to 5 days, while lipase elevations last longer, returning to baseline within 8 to 14 days. Serum lipase is more sensitive and specific than amylase for diagnosis of acute pancreatitis.

The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis requires two of the following three criteria:

Sudden onset of characteristic abdominal pain

Elevation of serum amylase and/or lipase above three times normal

Findings of pancreatic inflammation noted on imaging (CT, MRI, or ultrasound)

Imaging is not required for diagnosis of acute pancreatitis in patients who present with characteristic abdominal pain and elevated serum amylase or lipase.

Since the original Atlanta classification of acute pancreatitis in 1992, multiple predictive models for acute pancreatitis were proposed and there was much confusion regarding the terminology used for local complications and fluid collections from acute pancreatitis. In an attempt to address these issues, a revised Atlanta classification was published in 2012 which offers a detailed classification of acute pancreatitis, its severity and terminology for early and late pancreatic and peripancreatic collections.4

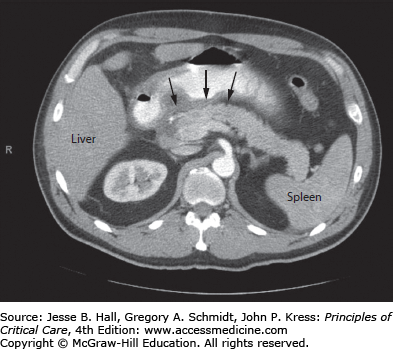

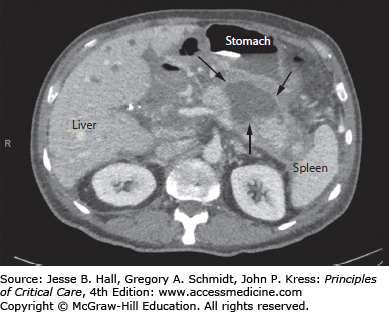

Types of Acute Pancreatitis: The revised Atlanta classification (Table 108-2) divides acute pancreatitis into two types, interstitial edematous pancreatitis (Fig. 108-1) and necrotizing pancreatitis (Fig. 108-2). Patients with interstitial edematous pancreatitis have diffuse inflammation of the pancreatic and peripancreatic tissue with enlargement of the pancreas. Necrotizing pancreatitis is seen in less than 10% of all patients with acute pancreatitis. These patients have necrosis of either pancreatic or peripancreatic tissue or both, in addition to the inflammatory changes. On contrast-enhanced CT scans, interstitial edematous pancreatitis appears as homogenous enhancement, while pancreatic/peripancreatic necrosis is seen as nonenhancing areas. Of note, the necrosis of pancreatic tissue can develop over days after onset of abdominal pain and can be missed on imaging done early during the course of disease.15,16

Revised Atlanta Classification (2012) for Pancreatic and Peripancreatic Fluid Collections

| Definition | Duration | CECT (Contrast-Enhanced CT) Features |

|---|---|---|

| Acute fluid collection (AFC) | <4 weeks |

|

| Acute necrotic collection (ANC) | <4 weeks |

|

| Pseudocyst (PP) | >4 weeks |

|

| Walled-off necrosis (WON) | >4 weeks |

|

The clinical course after an episode of acute pancreatitis is quite variable and it is of utmost importance to detect high-risk patients who will progress to severe, necrotizing pancreatitis in an effort to improve outcomes. Multiple clinical scoring systems have been used to predict the severity of acute pancreatitis. These scoring systems are very important because they can help recognize patients with severe acute pancreatitis who would require aggressive care in the intensive care unit. Ranson criteria have been shown to be moderately accurate in predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis,17-19 but it takes 48 hours after initial hospitalization to be calculated and involves laboratory values that are not routinely checked. As such, it is not frequently used. The Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Examination II (APACHE II) score was initially developed for critically ill patients and is currently the most widely used scoring system for severity of acute pancreatitis. It is as accurate as the Ranson criteria and is faster to calculate.20 Recently, a new scoring method known as bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis (BISAP) was developed in an attempt to recognize early disease severity.21

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree