Acute Neurological Complaints

Ronald I. Jacobson MD

Martin L. Kutscher MD

INTRODUCTION

Paroxysmal events include any sudden, unexpected change in body position or mental state that may be any duration in length. These events typically last seconds or minutes and may be simple or complex, recurrent, and stereotyped. They may stem from a neurological process and represent seizures, a movement disorder, or a normal mannerism or habit. Nonneurological causes may mimic these events as well, such as nonepileptic seizures or a response to pain in an infant. Display 46-1 demonstrates the varied differential diagnoses that must be considered.

DISPLAY 46–1 • Differential Diagnosis of Paroxysmal Events: Epileptic Versus Nonepileptic

Epileptic Events

Typical seizure is easy to differentiate

For atypical types, note pattern and frequency, effect of sleep, mental status change, postictal state, and electroencephalogram

Do not overlook focal seizures, simple partial seizures, myoclonic jolts, tics if single type, and repetitive sleep events

Nonepileptic Paroxysmal Events

Apnea

Benign paroxysmal vertigo

Breath-holding spells: pallid and cyanotic

Cardiac arrhythmias

Cataplexy

Colic (beware infantile spasms)

Daydreaming and microsleep

Episodic dyscontrol (rage)

Gastroesophageal reflux

Hyperexplexia (startle disease—may cause apnea and sudden infant death syndrome)

Hyperventilation syndrome (carpal-pedal spasm)

Hypoglycemia

Jittery or tremulous baby (postanoxia, hypocalcemia, hyponatremia, hypoglycemia)

Migraine

Moro reflex

Narcolepsy

Night terrors and other sleep disorders (exaggerated sleep myoclonus in infants)

Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS)

Paroxysmal choreoathetosis

Nonepileptic seizures (pseudoseizures or psychogenic seizures)

Sandifer’s syndrome (dystonic dyspepsia)

Shuddering attacks or benign shuddering of infancy

Spasmus nutans

Syncope

Tics and Tourette syndrome

Transient ischemic attacks

Seizure Disorders

INTRODUCTION

• Clinical Pearl

A seizure is an involuntary, sudden, and usually temporary alteration in neurological function that is produced from an abnormal electrical discharge from a localized or generalized neuronal source in the central nervous system.

Faced with a paroxysmal neurological event(s), the practitioner must first decide whether the event is a seizure, because this is the most significant clinical problem. Once an event has been determined to be a seizure, it must be further classified as to seizure type or seizure syndrome to determine appropriate work-up, prognosis, and treatment.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CLASSIFICATION

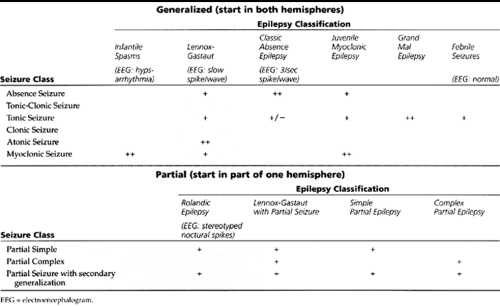

Seizures occur in about 8% of all people over a lifetime; however, the prevalence rate of epilepsy is between 0.5% and 1% of the population. Epilepsy begins before age 20 years in approximately 75% of patients (Holmes, 1987). Two different schemes are used in the classification of epileptiform events: classification by type of seizure and classification by epilepsy syndrome. The term seizure refers to the specific neurological event, such as an absence seizure or a tonic-clonic seizure, while the term epilepsy represents the chronic vulnerability or manifestation of seizure events. The term epilepsy syndrome refers to a full syndrome consisting of the type(s) of seizures seen in that syndrome, electroencephalogram (EEG) findings, typical age of patient, and typical prognosis. For example, absence seizure refers to the specific event of staring for several seconds; whereas absence epilepsy refers to the syndrome of a young, neurologically normal child whose EEG shows 3/second spike-wave discharges and whose seizures eventually remit in 90% of patients. The seizures and their corresponding epilepsy syndromes are divided into two broad categories: generalized and partial. By definition, primary generalized seizures are those that start simultaneously from both hemispheres. Partial seizures start from one location within a hemisphere (localization-related epilepsy). When a seizure focus spreads or generalizes to both hemispheres, the seizure and process is termed secondarily generalized seizures. The epilepsy syndromes are similarly divided into the generalized and partial epilepsies. The classification of seizures and the major childhood epilepsies is summarized in Table 46-1.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAM

• Clinical Pearl

The distinction between generalized and partial seizures is important for several reasons and affects the history, work-up, and treatment of a child with seizures.

During the history, one must determine if the seizure has any features of a focal onset event: Did the seizure start or affect one part of the body more than the others? Was there an aura? The latter question is important because a well-defined aura certainly means that the seizure began focally. The aura of a seizure is actually just its focal onset. During an aura, the rest of the brain is “watching” that part of the brain have its seizure. In contrast, a generalized seizure does not have a well-defined aura. Consciousness requires one working cerebral hemisphere and an intact brainstem. A generalized seizure, however, affects the entire brain at its onset and thus leaves “no one there” to be aware of the spell. Determination of an aura, then, is extremely useful. Remember to ask both the observer and the child about the specific onset of the seizure. Young children may be unable to verbalize an aura and may just demonstrate unusual behavior or run to their parent to get help. Also, the aura or focal onset of a seizure may be so brief that it is not noticed before secondary generalization of the seizure occurs. Thus, a focal seizure does not necessarily have an identifiable aura.

• Clinical Pearl

Because focal seizures are more likely to have underlying focal structural abnormalities, classification of focal versus generalized seizures may affect the child’s evaluation as well. In addition, different anticonvulsants are chosen based on the type of epilepsy classi

Generalized Seizures

Generalized seizures include absence, tonic-clonic, and minor motor seizures.

Absence Seizures

Typical absence seizures can be subtle or distinct, and they always recur during the course of several hours or days. Absence seizures typically begin in young school-aged children.

As with all generalized seizures, there is no aura. They consist of brief (3-30 seconds) staring spells, accompanied by a cessation of activity. Sometimes eye fluttering, mild lip movements, or twitches occur. There is no postictal state after a typical absence seizure.

As with all generalized seizures, there is no aura. They consist of brief (3-30 seconds) staring spells, accompanied by a cessation of activity. Sometimes eye fluttering, mild lip movements, or twitches occur. There is no postictal state after a typical absence seizure.

Tonic-Clonic Seizures

Tonic refers to continuous stiffening of the extremities. Clonic refers to the rhythmic alternating contraction and relaxation of the muscles. A tonic-clonic seizure is one that starts with continuous tonic stiffening and is then followed by a clonic phase of rhythmic jerks. Most tonic-clonic seizures are accompanied by loss of bladder control and are followed by a postictal state characterized by confusion, fatigue, headaches, muscle aches, and no memory of the seizure event. Note that partial seizures may have such rapid secondary generalization that they may be clinically indistinguishable from true primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

Minor Motor Seizures

There are two basic types of minor motor seizures. Myoclonic seizures are brief body jerks, often occurring in irregular flurries. Atonic (akinetic) seizures are drop attacks. They are so brief that consciousness has been regained by the time the child strikes the floor.

Partial Seizures

Partial seizures are classified into three types: simple partial, complex partial, and partial seizures with secondary generalization. Simple and complex partial seizures may be quite subtle with little noticeable change in appearance, or they may be readily apparent to any observer. Do not neglect to take a careful history from teachers, school nurses, and even the young child, who may be able to draw a picture or enact the event.

Simple Partial Seizures

Simple partial seizures begin focally in one hemisphere and do not impair the level of consciousness. They may consist of virtually any task of which the brain is capable, such as jerking of just one extremity or abnormal sensation of one part of the body.

Complex Partial Seizures

Complex partial seizures begin focally in one hemisphere and do impair the level of consciousness. There is usually a well-defined aura followed by confusion, which is accompanied by lip smacking, fumbling, twisting or turning, neck motion, eye deviation, or eyelid fluttering. Unlike absence seizures, these spells tend to last several minutes and are accompanied by an aura and postictal state.

Partial Seizures with Secondary Generalization

Although the secondary generalization may be the most striking feature to the family, it is the partial onset of these seizures that matters most to the clinician. A Jacksonian march is the label given to a seizure that spreads through the cortex of one hemisphere with resultant spread of the clinical seizure. The child may be aware of this focal march along one side of the body, and then lose consciousness as the seizure spreads to the other hemisphere during secondary generalization.

Selected Epilepsy Syndromes

Comprehensive discussion of the specific epilepsy syndromes is beyond the scope of this chapter. Although a few comments will be given here about some prototypical epilepsies, the reader is referred to standard texts such as those by Swaiman and Ashwal, 1999, and Wylie, 1997. Children with these conditions are typically managed by their primary care giver in conjunction with a neurologist with special competency in child neurology.

Benign Rolandic Epilepsy

Benign rolandic epilepsy is the most common type of focal epilepsy in school-aged children. Seizures are often focal, such as just a rhythmic twitch of the mouth. A clue to the diagnosis is their predominance during sleep, especially during the later part of sleep just prior to waking. The EEG

may be normal during wakefulness, yet sleep records show prominent stereotyped and simplified central-temporal spikes. The word “benign” is built into the name of this epilepsy syndrome because there is no serious underlying structural brain disorder. The response rate to anticonvulsant medication is excellent, and the remission rate is close to 100%. When treatment is indicated, carbamazepine (Tegretol) or the newest anticonvulsant agent oxycarbamazepine (Trileptal) is the appropriate anticonvulsant choice.

may be normal during wakefulness, yet sleep records show prominent stereotyped and simplified central-temporal spikes. The word “benign” is built into the name of this epilepsy syndrome because there is no serious underlying structural brain disorder. The response rate to anticonvulsant medication is excellent, and the remission rate is close to 100%. When treatment is indicated, carbamazepine (Tegretol) or the newest anticonvulsant agent oxycarbamazepine (Trileptal) is the appropriate anticonvulsant choice.

Absence (Petit Mal) Epilepsy

Absence epilepsy has commonly been referred to as petit mal seizures, but this is no longer the current terminology. This epilepsy syndrome usually occurs in neurologically normal preschool- and school-aged children who have absence seizures. These appear as brief staring spells during which the children stop their activity and are unresponsive to even strong stimuli. The EEG shows 3/second spike-wave activity, especially during hyperventilation.

• Clinical Pearl

Hyperventilation is an office maneuver that may precipitate absence seizures and is an important, simple, and quick diagnostic test. To perform an adequate hyperventilation test, the patient is requested to breathe in and out deeply for up to 3 minutes. Some younger patients need an aid, such as a piece of paper to blow with each breath. The patient is observed carefully during hyperventilation for any lapses in rhythmic breathing or staring. At the completion of hyperventilation, the patient is asked to count to 30—this is most revealing as the stream of speech and content is interrupted by an absence seizure.

The parent and physician together witness the clinical seizure during a hyperventilation maneuver, which allows precise confirmation that the parent’s observations at home correlate with the actual seizure event. Parents should be reassured that the increased respiratory rate during physical exercise does not induce seizures and is physiologically very different from static hyperventilation. About 10% of children with absence epilepsy will develop tonic-clonic seizures. Prognosis for remission occurring within 2 to 4 years after the onset of the seizures is excellent. Treatment is usually valproate or ethosuximide.

Infantile Spasms

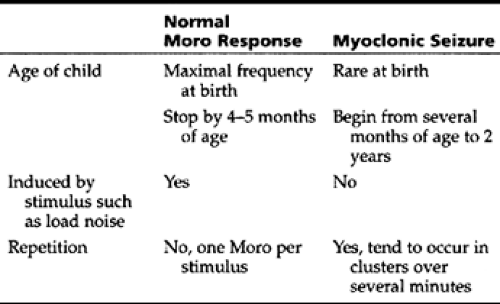

Infantile spasms, also known as West syndrome, is an epilepsy syndrome of infants beginning at 6 months and rarely commencing after age 3 years. Typical features include myoclonic seizures and an EEG finding of hypsarrhythmia (a triad of high-voltage multifocal spikes, disorganized background, and burst-suppression). These spasms usually cluster in bouts of 3 to 6 myoclonic jerks, momentary loss of tone, or as clusters of forceful extension or flexion of the head, legs, and trunk. The features distinguishing myoclonic seizures from the normal Moro response are given in Table 46-2. However, the distinction is not always clear.

Because early treatment (typically adrenocorticotropic hormone [ACTH] injections) appears to be critically important in an attempt to maintain neurologic function, prompt referral should be made to a pediatric neurologist whenever this diagnosis is considered.

Children with an identifiable underlying neurologic abnormality have a worse prognosis in regards to both developmental outcome and tendency to develop more complex or recurrent seizures (typically Lennox-Gastaut syndrome).

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA AND STUDIES

As an initial step, nonepileptiform conditions such as those in Display 46-1 need to be considered and evaluated as appropriate for conditions such as cardiac arrhythmias, prolonged QT interval, etc. Evaluation of seizures per se usually includes obtaining a complete blood count (CBC), SMA20, EEG (preferentially containing sleep), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. A noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan is frequently used as an initial screen in the emergency department but is not by itself generally a sufficient neuroimaging technique when evaluating seizures. It should be followed by a contrast CT scan or, quite preferentially, a MRI scan. Lumbar puncture should be performed if meningitis or encephalitis is a consideration. Toxicology screen may also be appropriate.

The diagnosis of an epileptiform event is established by carefully considering the history and correlating the EEG findings.

MANAGEMENT

The family needs to know that it is unlikely—although certainly not impossible—to be hurt or die from a seizure. The decision to treat with anticonvulsants is often made jointly by the family, the primary practitioner, and the neurologist. Factors in the decision include the type of seizures (including focality and duration), type of epilepsy syndrome, age of the child, family concerns, and EEG and MRI results.

• Clinical Pearl

In general, most neurologists do not prescribe anticonvulsants to children after a first, generalized, brief seizure in the setting of a normal EEG and MRI. In such a setting, the risk of a recurrent seizure is only about 30% (Swaiman & Ashwal, 1999).

The decision for each child must be individualized, taking into account the risks of seizures versus the risks of medication.

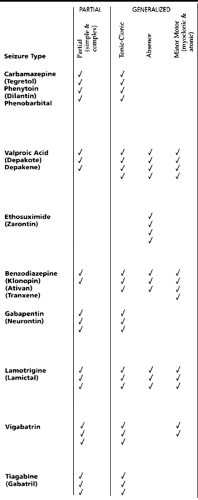

Anticonvulsant Therapy

An appropriate anticonvulsant is chosen based on safety, side-effects profile, and the type of epilepsy. The patient’s age, gender, presence of other medical problems, and use of other medications are significant factors to consider when selecting which anticonvulsant to prescribe. As demonstrated in Table 46-3, certain anticonvulsants are more effective for particular seizure types or syndromes. Carbamazepine, oxycarbamazepine, phenytoin, and phenobarbital are indicated mainly for the partial seizures, but they also work well for tonic-clonic seizures. When possible, carbamazepine or oxycarbamazipine is usually chosen first in order to avoid the hyperactivity frequently seen with phenobarbital and the gum hypertrophy and facial hirsutism of phenytoin. However, phenobarbital is usually used first in children younger than a few years. Valproate works particularly well for generalized seizures, including primarily generalized tonic-clonic and absence seizures. Valproate is effective for partial seizures as well. Risk factors for valproate hepatic failure include young age, neurologic impairment, and concomitant use of other anticonvulsants. Ethosuximide use is limited to absence seizures. The newer anticonvulsants such as gabapentin (Neurontin), topiramate (Topamax), tiagabine (Gabatril), and lamotrigine (Lamictal) are currently indicated as add-on therapy for partial seizures in children older than 12 years.

The use of Lamictal in children below 16 years is limited by the increased incidence of Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Oxycarbamazipine (Trileptal) is very similar to carbamazipine, which it may replace in selected patients because it has a broader anticonvulsant effect and has fewer potential side effects. Oxycarbamazipine was released in the United States market in February 2000 and is an approved anticonvulsant medication for add-on use in children and for add-on therapy and monotherapy in adults. These new medications are described in detail in several review articles and standard texts (Pellock, et al., 1998; Wyllie, 1997).

Laboratory testing for patients taking anticonvulsants needs to be individualized. In general, a CBC, differential, liver function tests, and drug levels (when available or indicated) are monitored 1 month into treatment, then monthly for several months, and then every 6 months.

Discontinuation of Anticonvulsants

Typically, children are treated with anticonvulsant agents for a period of 2 years without seizures. At that point, the EEG is repeated, and the possibility of tapering the medication is discussed with the family and child, as appropriate for the patient’s developmental or chronological age. After the complete clinical picture is considered, including the child’s seizure history, presence of side effects to continuing medical treatment, and personal lifestyle, the anticonvulsant may be tapered over a 2- or 3-month period. Risk factors for a relapse include initial difficulty in obtaining seizure control, partial seizures, an abnormal neurological examination, and an abnormal EEG.

First Aid and Accident Precautions

For any child with episodes of altered levels of consciousness, whether due to seizures or not, it is appropriate to counsel families regarding first aid and reasonable accident precautions (see Display 46-2). These precautions apply particularly until the child has been symptom-free for 1 year from the

beginning of diagnosis or after significant changes in anticonvulsant regimens. Practitioners should be familiar with their state’s driving laws for patients with seizures and/or loss of consciousness. Most states require that the patient be free from loss of consciousness episodes for 1 year prior to driving. If this degree of seizure control is met, the ongoing use of anticonvulsants does not preclude obtaining a driver’s license.

beginning of diagnosis or after significant changes in anticonvulsant regimens. Practitioners should be familiar with their state’s driving laws for patients with seizures and/or loss of consciousness. Most states require that the patient be free from loss of consciousness episodes for 1 year prior to driving. If this degree of seizure control is met, the ongoing use of anticonvulsants does not preclude obtaining a driver’s license.

DISPLAY 46–2 • First Aid and Accident Precautions for Seizure Patients

First Aid

Stay calm

Lay the child down with head to the side

Loosen tight clothing

Place something soft under the head

Clear the airway of food, debris, or vomit

Do not place anything in the child’s mouth

If the seizure persists for more than a few minutes, is followed by a prolonged postictal state, or is atypical, the child should be taken to the emergency room

All first seizures require prompt medical attention

Accident Precautions

No driving, or biking around cars

No climbing higher than the child’s height

1:1 supervision around water, including the bathtub and especially near or in shallow water when less caution is often exhibited (showers are usually left unsupervised)

Set hot water temperature in the house to lower than scalding temperature

Routine sports are allowed

• Clinical Pearl

The general principle in caring for patients with epilepsy is to encourage an independent lifestyle and to promote self-esteem whenever possible and to the fullest extent appropriate to the

▪ Status Epilepticus

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

Status epilepticus is defined as either continuous seizure activity lasting at least 15 to 20 minutes or intermittent seizure activity over at least a 15- to 20-minute period, during which time the patient does not regain consciousness. Status epilepticus is a neurological emergency, although long-term neurological damage is unusual. A study by Shinnar (Maytal, Shinnar, Moshe, et al., 1989) showed that most of the neurological damage seen after status epilepticus can be traced to the underlying etiology, and that 98% of children presenting in status epilepticus due to either idiopathic epilepsy or fever had a normal neurological outcome. There are several recent reviews on the treatment of status epilepticus in children (Pellock, 1998; Sabo-Graham, et al., 1998; Tasker, 1998). The most practical points are discussed in the following section.

MANAGEMENT

Supportive Treatment

It is a mistake to even consider anticonvulsant therapy until basic vital functions are evaluated and supported. As in any

acute situation, attention should be first focused on the ABCs—airway, breathing, and circulation.

acute situation, attention should be first focused on the ABCs—airway, breathing, and circulation.

During the initial phase of treatment, a focused history and physical examination should be performed. The entire stabilization and seizure control process should occur during a 30-minute timeline. Particular historical points include previous history of seizures; medications prescribed and medication compliance; the state of the child before the seizure; presence of fever, trauma, and possible ingestion. During examination, remember to look for evidence of infection and other organ system problems, particularly in the neck and abdomen. Careful fundoscopic examination is important, searching for papilledema and retinal hemorrhages.

Initial laboratory investigations should include blood for electrolytes, glucose, calcium, liver function tests, CBC, and lead level in selected patients. When appropriate, also obtain drug levels, arterial blood gases, and blood culture.

• Clinical Pearl

Always run an immediate fingerstick glucose test on any patient with an unexplained acute alteration of neurological function to assess the possibility of hypoglycemia.

The finding of hypothermia in a patient with or without an environmental exposure or infection may indicate the presence of hypoglycemia.

Anticonvulsant Therapy

The dosages for medications used in the treatment of status epilepticus are given in Table 46-4. Notice that recommended pediatric dosages and rates of administration tend to vary among the different medications and may depend on the medical condition of the patient and previously prescribed medications. For example, the sequential administration of intravenous (IV) phenobarbital and a benzodiazepam in a compromised patient will increase the possibility of respiratory depression; the rate of administration may need to be lowered to prevent the subsequent need for intubation. The administration of medications used to treat status epilepticus should not exceed adult maximum doses. Because these are potentially dangerous medications being used in a critical life-threatening circumstance, they should be used appropriately by an experienced health care team including the medical, nursing, and pharmacy staff members. The recommended sequence of supportive therapies and anticonvulsants is illustrated in Display 46-3.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree