Severity in acute pancreatitis: original versus revised Atlanta classification

1993

2013

Mild acute pancreatitis

Mild acute pancreatitis

Absence of organ failure

Absence of organ failure

Absence of local complications

Absence of local complications

Moderately acute pancreatitis

Local complications AND/OR

Transient organ failure [>48 h]

Severe acute pancreatitis

Severe acute pancreatitis

Local complications AND/OR

Persistent organ failure >48 ha

Organ failure

GI Bleed [>500 cc 24 h]

Shock [SBP ≤ 90 mmHg]

PaO2 ≤ 60 %

Creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dl

The RAC has three categories of clinical severity: (1) mild acute pancreatitis defined as the absence of systemic or local complications, (2) moderately severe acute pancreatitis, a new category defined as the presence of transient organ failure, deteriorating preexisting co-morbid disease and or the presence of local complications requiring prolonged stay or intervention, and (3) severe acute pancreatitis defined as persistent organ failure greater than 48 h [10–12].

In addition to this stratification, the RAC also differentiates the types of acute pancreatitis based on morphology. For example, while the pancreas will enhance normally on contrast enhanced CT in interstitial pancreatitis, there may be varying degrees of tissue necrosis in necrotizing pancreatitis [10–12].

The RAC further subdivides necrotizing pancreatitis into three major forms depending on whether the necrosis involves the pancreatic parenchyma, peri-pancreatic tissues, or combined necrosis of both the parenchyma and peri-pancreatic tissues. In addition, pancreatic collections in the early phase are classified as either acute peri-pancreatic fluid collections or acute necrotic collections. After a period of maturation, these can develop into either pseudo cysts or as walled off necrosis [10–12].

Scores for Organ Dysfunction

Necrotizing pancreatitis can be the inciting event leading to multisystem organ dysfunction. Over the past several years, there have been many attempts to quantify the severity of disease processes. Early scores such as Ranson’s criteria were an attempt to predict clinical outcomes based on the severity of acute pancreatitis. Although historically significant, it is no longer routinely utilized. Newer scores such as the multiple organ dysfunction score [MODS] or the sequential failure assessment score (SOFA) have been developed to evaluate organ dysfunction in the intensive care units. The RAC adopted the modified Marshall score for their definition of organ failure [13] (Table 10.2).

Table 10.2

Modified Marshall scoring system for organ dysfunction a

Organ system | Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

Respiratory renal | |||||

[PaO2/FiO2] | >400 | 301–400 | 201–300 | 101–200 | ≤101 |

Serum creatinine, μmol/L | ≤134 | 134–169 | 170–310 | 311–439 | >439 |

Serum creatinine, mg/dL | <1.4 | 1.4–1.8 | 1.9–3.6 | 3.6–4.9 | >4.9 |

Cardiovascular b | |||||

Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | >90 | <90, fluid responsive | <90, not fluid responsive | <90, pH < 7.3 | <90, pH < 7.2 |

Although previously routinely recommended to detect bacteria, percutaneous fine needle aspiration is no longer considered a mandatory requirement. Instead, clinical signs such as worsening or persistent fever or the presence of gas in peri-pancreatic collections are considered accurate predictors of infected necrosis in most patients [14].

Management

ICU Care

Patients with necrotizing pancreatitis should be admitted to the intensive care unit for aggressive fluid resuscitation and supportive care. The surgical team should work closely with surgical intensivists in monitoring the progress of these patients. Goal directed therapy should be based on both non-invasive and invasive clinical markers. These include heart rate, mean arterial blood pressure, and urinary output as well as stroke volume variation, echocardiograph examination, and laboratory assessments. Failure to aggressively fluid resuscitation these patients within the first 24 h of admissions is associated with increased rates of systemic inflammatory response syndrome and organ failure [4, 5, 7, 8]. Antibiotics are generally not recommended for prophylaxis of infected pancreatic necrosis. Several meta-analyses have shown that there are no significant differences in mortality, incidence of infected pancreatic necrosis, non-pancreatic infection, and surgical intervention. In fact, several studies have shown that there may even be an association with antibiotic use and pancreatic fungal infections. Therefore, the use of prophylactic antibiotics is not recommended. Antibiotics for treatment should be used for clinical suspicion for concurrent extra-pancreatic infection [15, 16].

Patients with acute severe pancreatitis are hypermetabolic with increased net protein catabolism, up to 40 g nitrogen/day. Enteral nutrition is an important mode of therapy in these critically ill patients and should be initiated within the first 72 hours of hospitalization. Multiple studies have shown that early nutritional support reduces catabolism and loss of lean body mass. Nutrition also helps modulate the acute phase response and may preserve visceral protein metabolism. In those patients with severe necrotizing pancreatitis that develop a prolonged paralytic ileus precluding complete enteral nutrition, it is still possible to administer small amounts of enteral nutrition. The route of nutrition delivery, either via the parenteral or enteral route, should be determined by patient tolerance. Enteral feeds are preferred and should be attempted in all patients. Nutritional markers should be monitored routinely. Some patients may require a combination of enteral and parenteral nutrition depending on their tolerance of enteral feeds. [17–20].

Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

Given the aggressive fluid resuscitation required for these patients, the acute care surgeon should always be concerned about the development of abdominal compartment syndrome. The clinical sequelae of this potentially fatal complication include abdominal distention, sustained elevated intra-abdominal pressure (greater than 25 mmHg measured by bladder pressure), decreased urine output, and increasing respiratory insufficiency. Paracentesis may be considered in the early stages to help with drainage of ascites that could be contributing to increased abdominal pressure. Should the concern for abdominal compartment syndrome persist, the definitive management is surgical decompression. A wound VAC is then placed for temporary abdominal closure [21].

Multidisciplinary Step-up Management

Clinical judgment should be used when considering pursuing pancreatic necrosectomy concomitant with abdominal decompression for compartment syndrome. It is advisable to delay surgical necrosectomy until pancreatic collections have become walled off to help delineate between viable and non-viable tissue [22, 23]. However, depending on the degree of necrosis, delayed operative management, despite wishful thinking, may not be possible. In this case, the patient can be expected to become sicker after exploration and debridement. All necrotic material should be debrided. Wide drainage of the pancreas including drains placed in the lesser sac, above the pancreatic bed, and below the level of the transverse mesocolon is encouraged [24].

The Step-Up Approach is another option for management of necrotizing pancreatitis [25, 26]. This approach utilizes a percutaneously placed drain [12 Fr] drain with assistance of interventional radiology through the left retroperitoneum. Proper positioning of this initial drain cannot be overstated, and the surgical team should have direct input into the exact location planned by interventional radiology (Fig. 10.1). A poorly placed drain will make it difficult to perform the video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement (VARDS) and potentially increase the chance of injury [27]. After placement of the initial drain, the patient is observed for clinical improvement as evidenced by drop in fever, WBC, and improvement of other physiologic parameters as well as resolution of fluid collections and inflammatory foci seen on CT scan. If no improvement is seen over the next 72 hours, upsizing of the drain should be considered. If this fails, the patient should proceed to VARDS [28–34] (Fig. 10.2).

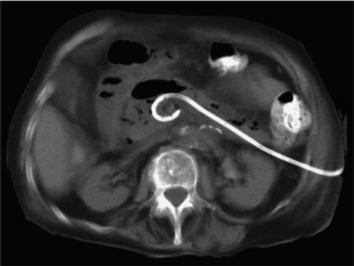

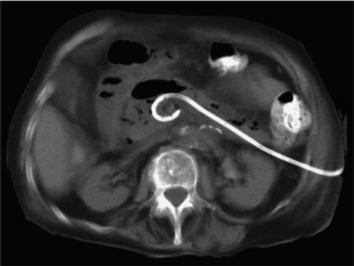

Fig. 10.1

Step-up approach: initial left-sided drain placement into retroperitoneum. From van Santvoort et al. [27, Fig. 1], with permission from Elsevier

Fig. 10.2

Single port VARDS

Surgery is preferably postponed until at least 4 weeks from the onset of the disease [24]. This is considered essential as it allows for peri-pancreatic collections to sufficiently demarcate and the wall to mature, thus optimizing conditions for debridement. The VARDS technique we use is similar to that described by van Santvoort et al. The patient is placed in supine position with the left side elevated 30° to 40°. A subcostal incision approximately 5 cm in length is placed in the left flank at the mid-axillary line, close to the exit point of the percutaneous drain.

With the help of CT images and by using the in situ percutaneous drain as a guide into the peri-pancreatic collection, the fascia is dissected and the retroperitoneum is entered. The cavity is cleared of purulent material using a standard suction device. The first necrosis encountered is carefully removed with the use of long grasping forceps. Loose necrotic material is removed while periodic irrigation and continuous suction are performed to enhance vision as the percutaneous drain is followed as a road map deeper into the cavity (Fig. 10.3). When debridement can no longer be performed under direct vision, a single extra-long laparoscopic port is placed into the incision and a 0° videoscope is introduced. At this stage, CO2 gas (10 L/min) can be infused through the percutaneous drain, still in position, to inflate the cavity, thereby facilitating inspection. Under videoscopic assistance, further debridement of retained necrotic tissue is performed with laparoscopic forceps. Complete necrosectomy is not the ultimate aim of this procedure. Only loosely adherent pieces of necrosis are removed, thereby keeping the risk of tearing underlying blood vessels to a minimum. Overly aggressive necrosectomy of un-demarcated, necrotic tissue will increase the chance of injury and bleeding. The main complications of VARDS remain hemorrhage and colonic perforation. Significant retroperitoneal bleeding has a reported incidence of as high as 16–20 %. In the case of extensive bleeding, packing of the retroperitoneal cavity should be performed, either as definite treatment or as a bridge to laparotomy or angiographic coiling in the situation of persistent hemorrhage. When the bulk of necrosis is removed, the cavity is irrigated with saline until the fluid becomes clear. The percutaneous drain is removed, and two large-bore single-lumen drains are positioned in the cavity extending through the edges of the incision. Multiple large-bore drains are placed to allow for postoperative lavage. The fascia and skin are closed, and the drains are sutured to the skin. Continuous postoperative lavage is performed with 10 L of normal saline or dialysis fluid per 24 hours until the effluent is clear. One week after the procedure repeat CT is performed to evaluate resolution [35–38].