Key Clinical Questions

What are the key questions that an examiner should ask when approaching a patient with acute back pain?

What should the examiner look for on physical examination?

What are “red flag” findings that should heighten your level of concern when approaching a patient with acute back pain?

What are some nonspinal etiologies of back pain?

Introduction

Back pain has a major impact on patient well-being and healthcare budgets in developed nations. It is the fifth leading cause of hospital admissions, and the third most common reason for surgical procedures. Back pain ranks second only to upper respiratory tract infections as a reason for primary care physician office visits. The annual prevalence of chronic low back pain ranges from 15% to 33%, and 7% of adult patients may have low back pain at any given time. In the United States, back pain, including chronic low back pain, is the leading cause of disability in subjects younger than 45 years of age. Individuals with back pain in the United States account for $90 billion in direct healthcare expenditures, and approximately 2% of the U.S. workforce is compensated for back injuries each year.

Roughly 95% of visits for back pain stem from benign causes. However, in hospitalized patients, the percentage with serious pathology may be higher, so the hospitalist needs to have a high index of suspicion. This chapter focuses on the initial evaluation of acute low back pain in patients admitted to the hospital, as well as patients hospitalized for other reasons who develop back pain as a complication of hospitalization.

Pathophysiology

The function of the anterior spine is to absorb the shock of body movements such as walking and running. The function of the posterior spine is to protect the spinal cord and nerves, and to stabilize the spine by providing sites for attachment of muscles and ligaments. The normal alignment of the spine is notable for:

Movements of the cervical and lumbar regions are greater than the thoracic regions during activity. The elasticity of vertebral disks—largest in the cervical and lumbar regions—allow the bony vertebrae of the spine to move easily upon one another. Elasticity declines with age.

ACUTE ABDOMINAL AND BACK PAIN IN AN EMERGENT SETTING An 81-year-old man with a history of myocardial infarction 10 years ago presented with new-onset low back pain and crampy abdominal pain that had begun 2 hours prior. He had never had this type of back pain before. His exam revealed a blood pressure of 110/70. His creatinine was 2.5 with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of <35/mL/1.73 m2 which is his baseline after his myocardial infarction 10 years ago. He had good pedal pulses, and his abdominal exam revealed a soft abdomen with diffuse tenderness and without rebound or guarding and normal bowel sounds. The patient’s back and abdominal pain improved after narcotic administration. A computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast showed an abdominal periaortic hematoma. A 2D echocardiogram did not identify a dissection in the ascending aorta or aortic arch. A stable descending abdominal dissection is diagnosed and a vascular surgery consultation is obtained for further management. |

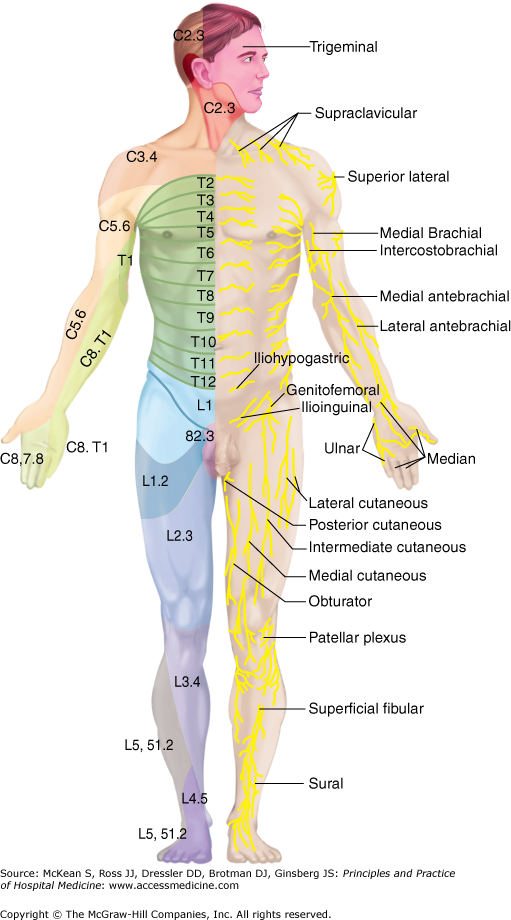

Visceral pain is poorly localized pain that is usually bilateral. It may arise from distension of abdominal organs, torsion, or contraction. The pain radiates along the dermatomes that innervate the involved organ (Figure 75-1). For this reason, it is possible to have pain referred to the back (ie, the posterior portion of the spinal segment that innervates the diseased organ).

Because of visceral innervation, diseases involving the pelvic organs, kidneys, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and thorax may initially cause isolated back pain.

In general, the referral patterns are as follows:

- Upper abdominal diseases: pain T8 to L1 or L2

- Lower abdominal diseases: L2 to L4

- Pelvic diseases to the sacral region

Usually the patient has associated thoracic, abdominal, or pelvic pain depending on the location of the diseased organ. For example, sudden lumbar pain in a patient with a coagulopathy may indicate retroperitoneal hemorrhage. Changes in position do not usually affect visceral pain (Table 75-1).

| Visceral Disease | Referred Pain | Pathology | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptic ulcers, tumors of posterior wall of stomach or duodenum | Midline back or paraspinal pain | Retroperitoneal extension | |

| Pancreatitis, pancreatic tumors | Back pain to the right or left of the spine | Involvement of head of pancreas (right sided); body or tail (left sided) | Chapter 156: Pancreatitis: Acute and Chronic |

| Retroperitoneal structures | Paraspinal pain that radiates to the lower abdomen, groin, or testicles | Hemorrhage, tumors, pyelonephritis | |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm | Isolated LBP (15–20% of patients) | Contained rupture | Abdominal pain, shock, back pain < 20% of patients; hypotension 50%; 2 of 3 features in 66%; typical patient elderly male smoker |

| IIiopsoas mass or abscess | Unilateral lumbar pain to groin, labia or testicles | ||

| Colitis, diverticulitis or colon cancer | Midlumbar pain ± beltline distribution around body | Lesion in transverse or proximal descending colon (mid or left L2–3); sigmoid (upper sacral) | Lower abdominal pain or isolated back pain or both |

| Endometriosis, uterine cancers, uterine malposition, menstrual pain, remote radiation therapy to pelvis | Sacral pain | Lower back pain rare except in disorders involving uterosacral ligaments | |

| Pregnancy | Lower back pain radiating to one or both thighs | Last weeks of pregnancy | |

| Chronic prostatitis; prostate cancer metastatic to spine; ureteral obstruction from stones | Lumbosacral back pain | ||

| Infectious, inflammatory, or neoplastic renal disease; renal vein thrombosis | Ipsilateral lumbar sacral pain | Chapter 251: Kidney Stones; Chapter 205: Urinary Tract Infections | |

| Hip pain | May mimic lumbar spine disease | Patrick sign or heel percussion sign may help distinguish from spine etiologies |

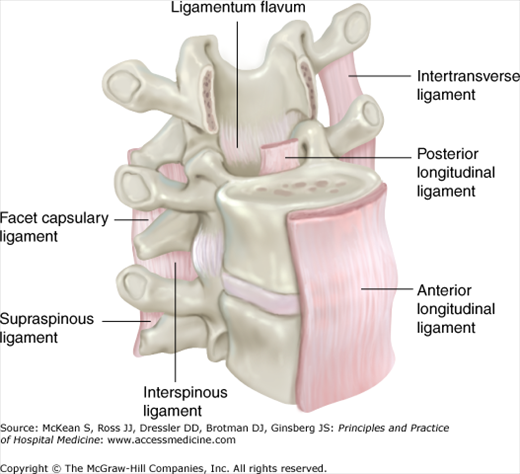

Back pain may be produced by irritation or compression of local sensory nerve endings. Diseases of any of the pain-sensitive structures of the back—periosteum of the vertebrae, dura, facet joints, annulus fibrosus, epidural veins, and the posterior longitudinal ligament—may cause back pain without nerve root compression (Figure 75-2).

Back pain may result from direct injuries (usually musculoligamentous, but sometimes fractures with or without spinal cord trauma) and degenerative processes (spinal stenosis, disk herniation, changes in the intervertebral disks and other structural abnormalities). Ordinarily, the nucleus pulposus and inner annulus fibrosus do not have innervation. However, inflammatory cytokines, ingrowth of pain nerve fibers into the damaged disks, and nerve root injury due to disk herniation have been hypothesized as possible mechanisms of pain related to disk disease. Substantial genetic influences rather than age-related changes determine the incidence of disk disease which recurs in 40% of patients within six months. Pain from the lumbar spine may be felt in the coccyx, hips or buttocks. The pain should not shoot down the posterior thighs without disk impingement on an exiting nerve root.

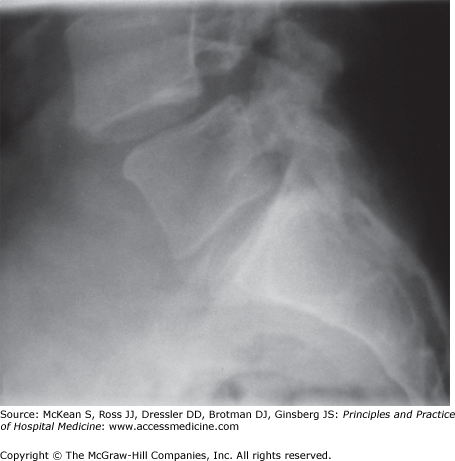

Structural abnormalities specific to the spine include congenital and acquired anomalies. Spondylolysis is a defect in the pars interarticularis leading to vertebral body instability of the lumbar vertebral bodies that may lead to bilateral stress fractures. In such cases, the activity related persistent back pain is the main feature of the disease.

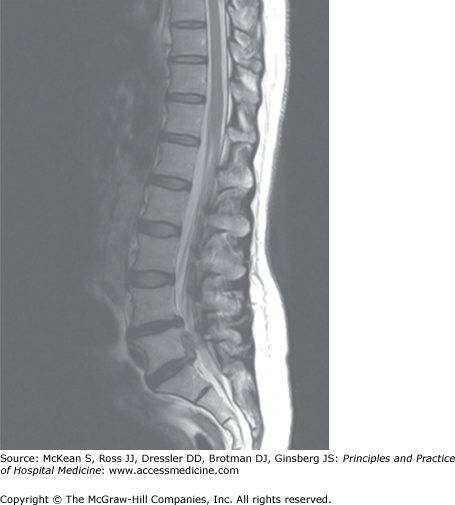

Alterations of the microarchitecture of the vertebral body may lead to compression fractures and localized back pain (Figure 75-3). The pain may be exacerbated by movement, relieved by lying flat in bed, and may radiate to the extremities. Common underlying causes include immobilization, endocrine disorders (hyperparathyroidism, hyperthyroidism), malignancy (multiple myeloma, metastatic carcinoma), chronic glucocorticoid use, and osteoporosis and osteomalacia.

Bacteremia in the setting of endocarditis, pneumonia, or pyelonephritis may seed the vertebral bodies and discs, leading to osteomyelitis and diskitis. Less commonly, vertebral osteomyelitis may arise from local infection, such as postoperative infection after surgery. Extension of infection can lead to meningeal involvement, with an epidural or subdural abscess. The thoracolumbar vertebral bodies are the usual sites of involvement, but any area of the spine may be affected. After spinal surgery, reverse extension of the infection from the disc space to the endplates may occur. Mycobacterium tuberculosis of the spine, also known as Pott disease, is common in patients from endemic regions, and typically affects the lower thoracic spine.

Arthritic spine diseases include ankylosing spondylitis (AS), reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease associated spondyloarthritis and undifferentiated spondyloarthritis. Patients may report insidious onset of low back pain and buttock pain. A suggestive feature is worsening pain with rest, or back pain that awakens the patient at night. Patients with AS frequently report alternating upper buttock or lower lumbosacral pain, deep in nature, which worsens on long car rides or with prolonged sitting. The patient may improve on ambulation or exercise. Patients with psoriatic arthritis, as in reactive arthritis, have their spine involved much less frequently than in AS.

Nerve roots exit from the vertebral bodies. They may be injured at any point along their intraspinal course to their exit at the intervertebral foramen. Facet joint hypertrophy can produce unilateral radicular symptoms due to bony compression of the nerve roots. With worsening facet osteoarthritis, cysts may protrude, and cause further narrowing of the spinal canal. Referred pain can be associated with radicular pain. For example, a retroperitoneal bleed can cause neuropathic pain along the femoral nerve.

Pain originating from spinal nerve roots may be referred to the extremities. For example, pain originating from the lumbar region may be referred to the buttocks or legs, or localized to the lumbar region. Diseases of the upper lumbar spine may cause pain localized to the lumbar region, groin or anterior thighs. Diseases of the lower lumbar region may cause pain referred to the buttocks, posterior thighs, or rarely, the calves or feet.

Radicular pain is often aggravated by postures that stretch nerves and nerve roots. Because the sciatic nerve (L5 and S1 roots) passes posterior to the hip, sitting increases pain arising from stretching of the sciatic nerve. Pain arising from the femoral nerve (L2, L3, and L4 roots), however, will not be stretched from the sitting position because the femoral nerve passes anterior to the hip.

Disk herniations may impinge upon a nerve root, thereby causing radicular pain. The L5 and S1 nerve roots are involved in close to 95% of lumbar-disk herniations (Figure 75-4). These patients will describe a subacute to chronic, deep, burning, aching lower back pain that involves the buttocks and radiates down the posterior thigh to the posterolateral aspect of the calf.

Radiating pain may be elicited by lifting heavy objects, straining to have a bowel movement, coughing, or sneezing.

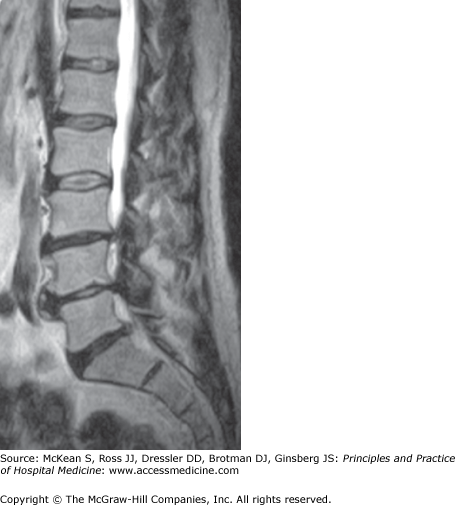

Spondylolisthesis or anterior slippage of one vertebral body, pedicles, and superior articular facets over another, may arise from congenital anomalies of the lumbosacral spine with one example being spondylolysis (Figure 75-5); other common causes include degeneration, osteoporosis, trauma, prior surgery, infection, and tumor. When symptomatic, it may cause low back pain, tightness of the hamstring muscles, and nerve root injury, most frequently of L5.

Lumbar adhesive arachnoiditis causes radicular pain due to injury of the subarachnoid space. Multiple lumbar operations, chronic spinal infections, spinal cord injury, intrathecal injection, demyelination polyneuropathies, or neoplastic infiltration can cause inflammation with subsequent fibrosis.

Lumbar spinal stenosis causes radicular pain due to a narrowed spinal canal that impinges on the spinal cord during certain postures. Spinal stenosis may develop secondary to congenital defects such as spondylolysis and acquired causes such as spondylolisthesis or adjacent to prior sites of fusion surgery. The discomfort, commonly referred to as neurogenic claudication, radiates from the lower back to the buttock, and even down to the proximal legs (Figure 75-6). The pain is worse with prolonged walking and standing and much better on sitting or change in posture—a clear distinction from the inflammatory back pain syndromes.

Cauda equina syndrome (CES) can cause acute or subacute back pain. By definition, it is associated with serious neurologic deficits, such as impairment of bladder, bowel, or sexual function and perianal “saddle” numbness. A centrally herniated disk is the most common cause of this syndrome. Less common causes of the CES include spinal injury, spinal stenosis, neoplasms, abscesses, tuberculosis, AS, spinal anesthesia, back manipulation, or postoperative complications such as hematoma. CES can present acutely as the first symptom of lumbar disc herniation, or insidiously with slow progression to numbness and urinary symptoms. CES need not present with complete urinary retention and reduced urinary sensation. The loss of desire to void and a poor stream are symptoms of an “incomplete” CES. This condition requires a high index of suspicion to make the diagnosis, especially if the patient has preexisting urinary difficulties. In fact, patients have inappropriately undergone prostate surgery with no improvement in their symptoms prior to reaching the correct diagnosis of CES.

Spasms of taut paraspinal muscles will produce nonspecific localized dull pain aggravated by abnormal posture. 90% of patients with the poorly defined muscle sprain or strain—the most common cause of nonemergent back pain—will recover within two weeks. Heavy lifting, pushing, pulling, prolonged walking and standing, and driving are associated with this type of back pain.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree