INTRODUCTION

The diagnoses discussed in this chapter are challenging, since emergent surgical conditions in children may present with predominant symptoms other than pain, including vomiting, fever, irritability, or lethargy. Table 130-1 classifies conditions by age, although many conditions cross categories.

| Age | Emergent | Nonemergent |

|---|---|---|

| 0–3 months old | Necrotizing enterocolitis Volvulus Incarcerated hernia Testicular torsion Nonaccidental trauma Hirschsprung’s enterocolitis | Constipation Acute gastroenteritis Colic |

| 3 months–3 years old | Intussusception Volvulus Testicular torsion Appendicitis Vaso-occlusive crisis | Urinary tract infections Constipation Henoch-Schönlein purpura Acute gastroenteritis |

| 3 years old–adolescence | Appendicitis Diabetic ketoacidosis Vaso-occlusive crisis Ectopic pregnancy Ovarian torsion Testicular torsion Cholecystitis Pancreatitis Urinary tract infections Tumor Pneumonia | Streptococcuspharyngitis Inflammatory bowel disease Pregnancy Renal stones Peptic ulcer disease/gastritis Ovarian cysts Henoch-Schönlein purpura Constipation Acute gastroenteritis Nonspecific viral syndromes |

The pathophysiology of abdominal pain is discussed in chapter 71, Acute Abdominal Pain and gynecologic causes are discussed in chapter 97, Abdominal and Pelvic Pain in the Nonpregnant Female.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The assessment of young children depends on careful observation for subtle clues. Stillness suggests conditions that irritate the peritoneum, such as appendicitis. Writhing for a position of comfort suggests obstruction, such as intussusception or renal colic.

Inspect, auscultate, and then palpate the abdomen, starting away from the expected area of maximal tenderness. Bringing the knees up relaxes the abdominal muscles. Move the hips to test for hip pathology or irritation caused by appendicitis or a psoas abscess. Thoroughly examine the diaper area to identify testicular torsion, paraphimosis, hair tourniquet, hernia, and imperforate hymen, as the young child may be unable to articulate problems in that area and the older child may be embarrassed to do so. Rectal exam may identify gross or occult blood, constipation, abnormalities of anogenital anatomy, and inflammatory processes. Evaluate for extra-abdominal causes of abdominal pain such as pharyngitis or pneumonia.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS BY AGE GROUP

The major life-threatening diagnoses in young infants are necrotizing enterocolitis, malrotation with midgut volvulus, incarcerated hernias, and nonaccidental trauma. Young infants typically eat every 2 hours, so inconsolability and lethargy with poor feeding are signs of serious disease. The maxim that bilious vomiting portends a surgical emergency until proven otherwise is well supported, since between 27% and 51% of children with bilious vomiting require surgery.1

Intermittent, paroxysmal pain is often associated with intussusception, colic, and gastroenteritis. Necrotizing enterocolitis and volvulus are associated with constant pain. Pain after feeding may be caused by gastroesophageal reflux. Pyloric stenosis causes progressive painless projectile vomiting followed by renewed interest in feeding.

Past medical history includes the complications of pregnancy and delivery. Constipation, with a history of not passing meconium within the first 24 to 48 hours of life, suggests Hirschsprung’s disease. Hirschsprung’s enterocolitis is a serious complication that presents with explosive diarrhea, fever, vomiting, abdominal pain, and distension. It is common in the first 2 years after resection of the aganglionic segment, but also occurs in patients with undiagnosed disease.

Fever in this age group requires thorough investigation (see chapter 116, Fever and Serious Bacterial Illness in Infants and Children).

Intussusception, urinary tract infections, testicular torsion, and accidental and nonaccidental trauma are serious causes of abdominal pain in older infants and toddlers. Malrotation with midgut volvulus and appendicitis are less common but remain considerations. Constipation is a common cause of abdominal pain that can be severe and often begins around the time of toilet training. Parents may not offer a bowel history unless asked.

Stranger anxiety is prevalent at this age. Take a few moments to gain the confidence of the child before any examination or procedures. It may be helpful to ask a parent to palpate the child’s abdomen while you observe, before palpating yourself or with the toddler’s assistance. Observe the child while coughing, walking, or jumping as a test for peritoneal irritation. Toddlers may not be able to differentiate pain from nausea.

Diagnoses in this age group include problems that are common in adults. Appendicitis is the most common surgical emergency.

Other important etiologies are diabetic ketoacidosis (chapter 145, Diabetes in Children), urinary tract infection (chapter 132, Urinary Tract Infection in Infants and Children), testicular torsion, ectopic pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease (chapter 133, Pediatric Urologic and Gynecologic Disorders), pancreatitis, inflammatory bowel disease, cholelithiasis (chapter 130, Acute Abdominal Pain in Infants and Children), sickle cell anemia (chapter 142, Sickle Cell Disease in Children), Henoch-Schönlein purpura, and renal colic (chapter 134, Renal Emergencies in Children). Upper respiratory symptoms may be associated with mesenteric adenitis, which may mimic appendicitis.

An examination of the testicles is required. If two testicles cannot be identified, consider torsion of an undescended testis. Perform a pelvic examination in sexually active girls. Adolescents may offer additional information if some of the history is taken with parents out of the room.

Bedside glucose measurement is a first step in the evaluation of any ill-appearing child or in cases of persistent vomiting or poor oral intake. Obtain a chemistry panel if there is suspicion for electrolyte or renal abnormalities in ill-appearing children and in the first 6 months of life, in which sodium or metabolic abnormalities are more common. Urinalysis identifies urinary tract infection, microscopic hematuria, and pregnancy. The WBC count is a poor screening test for undifferentiated abdominal pain.

US is the first-line test for appendicitis, pyloric stenosis, intussusception, testicular torsion, and biliary and gynecologic pathology. CT scan is the most sensitive study for appendicitis, urolithiasis, and intra-abdominal abscesses and may uncover a wide variety of pathology. Current thinking is that one fatal cancer will be induced by every 1000 CT scans performed on young children.2 IV contrast has a significant risk of allergic reactions and contrast nephropathy; therefore, reducing unnecessary CT use should be a goal of emergency physicians.

Plain radiographs give a much lower radiation dose (1/600th the dose for a chest radiograph compared with an abdominal CT).3 Radio-graphy should be used selectively to exclude or support specific diagnoses, not for undirected screening. Free air from a perforation can be seen on upright or left lateral decubitus views, although these are insensitive tests. Barium oral or rectal contrast should never be given if perforation is suspected; instead, use water-soluble contrast.

Contrary to fears that analgesics may mask surgical conditions, analgesia improves the physician’s ability to assess pain and does not worsen outcomes. See chapter 113, Pain Management and Procedural Sedation in Infants and Children.

SPECIFIC CONDITIONS

Necrotizing enterocolitis is a neonatal disease thought to be caused by an immune overreaction to an insult to the intestine followed by inflammation, bacterial translocation, and coagulation necrosis of the intestine. Overall mortality is 15% to 30%, with many survivors left with short bowel syndrome and growth retardation.4 While necrotizing enterocolitis is largely a disease of prematurity, 10% of cases occur in term infants.5 Predisposing conditions include congenital heart disease, sepsis, neonatal asphyxia, polycythemia, and hypotension.6 The range of mean ages at onset of disease is between 2 and 9 days of age. Therefore, although the disease rarely presents outside of the neonatal intensive care unit, its severity makes it an important consideration in near-term infants or those with comorbidities in the first 3 weeks of life.

Presenting signs and symptoms are poor feeding, lethargy, abdominal distension, bilious vomiting, temperature instability, apnea, and abdominal tenderness. Gross or occult blood in the stool increases the likelihood of necrotizing enterocolitis but is neither sensitive nor specific.7

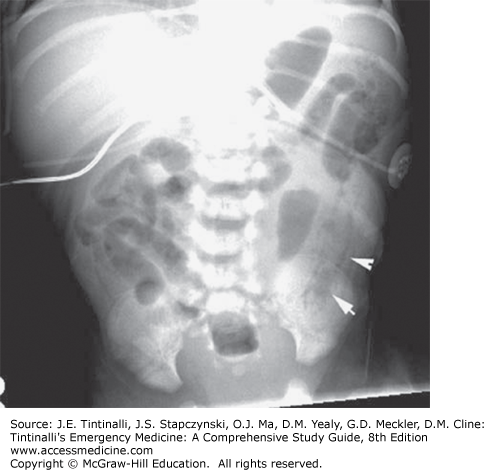

Obtain antero-posterior and lateral decubitus abdominal radiographs. Inclusion of the chest will screen for cardiopulmonary abnormalities. Early in the disease, abdominal radiographs may show signs of ileus or obstruction. Pneumatosis intestinalis (air in the bowel wall) and portal venous gas are both pathognomonic (Figure 130-1),8 but normal abdominal radiographs do not exclude the disorder.

FIGURE 130-1.

Plain abdominal film demonstrating air in the intestinal wall (arrows), which is pathognomonic of necrotizing enterocolitis. [Reproduced with permission from Strange GR, Ahrens WR, Schafermeyer RW, Wiebe RA: Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 3rd ed. © 2009. The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. New York, Figure 9-12.]

Evaluation must include a search for underlying causes, especially sepsis. Management includes nothing by mouth status, gastric tube decompression, aggressive IV hydration, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and surgical consultation. Consider ampicillin to cover gram-positive organisms, gentamicin or cefotaxime for gram-negative organisms, and metronidazole or clindamycin for anaerobes.9 Although necrotizing enterocolitis is first managed medically, many cases require resection of necrotic bowel. Admit to intensive care.

Volvulus is a life-threatening complication of malrotation. Eighty percent of malrotation presents within the first month of life and 90% within the first year, but it can present at any time in life.10 At approximately 10 weeks of gestation, the growing intestines return to the abdomen from the yolk sac, and the midgut undergoes a 270-degree counterclockwise turn around the superior mesenteric artery. Abnormal rotation can leave the cecum high in the abdomen, with its peritoneal attachments (Ladd’s bands) crossing the duodenum. Down’s syndrome, heterotaxy, and duodenal atresia are associated with malrotation.

The child may be well until the malrotated gut twists (volvulus) or becomes obstructed by Ladd’s bands, causing ischemia.

Volvulus is a surgical emergency as it can result in gangrene of the entire midgut within hours. The infant with volvulus often has no significant past medical history and presents with the abrupt onset of constant abdominal pain, bilious vomiting, abdominal distention, and irritability. Patients with volvulus are typically ill appearing and may have signs of shock. The abdomen is diffusely tender and distended and may be rigid. Intermittent volvulus may present with stable vital signs and focal tenderness on abdominal examination. The absence of fever can be helpful in distinguishing volvulus from sepsis.

Imaging studies should not delay surgical consultation, as rapid detorsion of the volvulized bowel is necessary to prevent loss of the entire small intestine. Upper GI series with contrast remains the test of choice for diagnosing malrotation with sensitivities of 93% to 100% for malrotation and 54% to 79% for volvulus.11 The normal location of the duodenojejunal junction is at the level of the duodenal bulb and to the left of the spine. In malrotation, the junction is commonly located low and to the right of the spine. If midgut volvulus is present at the time of the study, there may be an abruptly tapered cutoff of contrast in the duodenum (bird’s beak) or a corkscrew appearance of the bowel. If concern persists after a negative study and surgical consultation, options for additional evaluation include repeat upper GI series to exclude intermittent volvulus, abdominal CT, US, and contrast enema.

Plain abdominal radiographs are neither sensitive nor specific for malrotation. The most common findings on plain abdominal x-ray are an air-filled stomach with little distal gas, which may show a distal obstruction, nonspecific, or even normal gas pattern.12

Treatment consists of resuscitation and immediate surgical consultation. Electrolytes, CBC, coagulation studies, and a type and cross-match for packed red blood cells are helpful to guide resuscitation and operative management.

Intussusception is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction in children under 2 years of age. It is rare before 2 months. The male:female ratio is 2:1.13,14

Intussusception occurs when one segment of the intestine telescopes into another, usually the ileum into the colon. Constriction of the mesentery results in engorgement of the intussusceptum and bowel ischemia. In infants, lymphoid hyperplasia from viral illness may cause a “lead point,” which drags one portion of bowel into another. In older children, causes of intussusception include Meckel’s diverticulum, intestinal polyps, congenital duplications, lymphoma, and Henoch–Schönlein purpura, and possibly exposure to antibiotics.15

Intussusception is notoriously difficult to diagnose because its two common presentations, intermittent pain and lethargy, are insensitive signs of intussusception. The classic presentation of the “intermittentsception” is an infant aged 5 to 12 months who suddenly develops a few minutes of severe abdominal pain with the legs drawn to the chest and who then appears well until the next episode of pain. An alternate presentation is an infant with unexplained lethargy, which may divert the provider to an evaluation for altered mental status. Vomiting is not usually present at first but develops over 6 to 12 hours and may be bilious.

The physical examination between attacks may be normal, although a sausage-shaped mass may be palpated in the right upper quadrant. Occult blood is found in 70% of stools and gross blood in about 50%, although it rarely resembles the classic “currant” jelly.16,17

A history consistent with the intermittent symptoms of intussusception should prompt further evaluation or observation even if the patient is asymptomatic at the time.

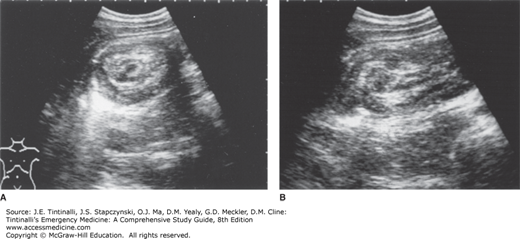

US should be the first study when the diagnosis is ambiguous. In research settings, the accuracy of US for intussusception is nearly 100% (Figure 130-2).

Children with a high suspicion of intussusception should undergo immediate air-contrast enema, which is both diagnostic and therapeutic.17 Prepare the child for reduction with boluses of normal saline, as volume loss due to intestinal edema, decreased intake, and vomiting is a common comorbidity. A surgeon should be notified prior to air-contrast enema in case the reduction is unsuccessful or perforation occurs. Children with peritonitis, with free air on plain radiographs, or who are in shock should not undergo air-contrast enema and require emergent surgical reduction.

Plain abdominal radiographs are not highly useful unless needed to rule out perforation, but they may show a mass or paucity of bowel gas in the right abdomen, a “crescent sign” where the curved edge of one segment of bowel visibly protrudes into another, or an obstructive pattern (Figure 130-3).16

Children have traditionally been admitted after enema reduction because of a 10% recurrence rate, usually within the first 24 to 48 hours.17 However, discharge after a few hours of observation to exclude complications may be appropriate in children with a normal WBC count, who can tolerate oral intake, and who can easily return should they have a recurrence.18 A recurrence should prompt a second enema reduction. Further recurrences may require surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree