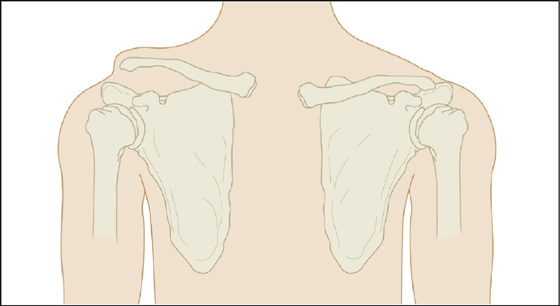

Figure 96-1 A, The most common mechanism of injury to the AC joint results from a direct blow onto the tip of the shoulder. B, An indirect force, such as a fall onto the elbow, may also disrupt the AC joint. (Adapted from Buss DD, Watts JD: Acromioclavicular injuries in the throwing athlete. Clin Sports Med 22:327-341, 2003.)

Signs such as swelling, abrasions, or bruising may be evident, either on the superior shoulder, implying a direct mechanism, or on the elbow or forearm, implying an indirect mechanism. The AC joint is tender to palpation. (It is superficial and easily palpated.)

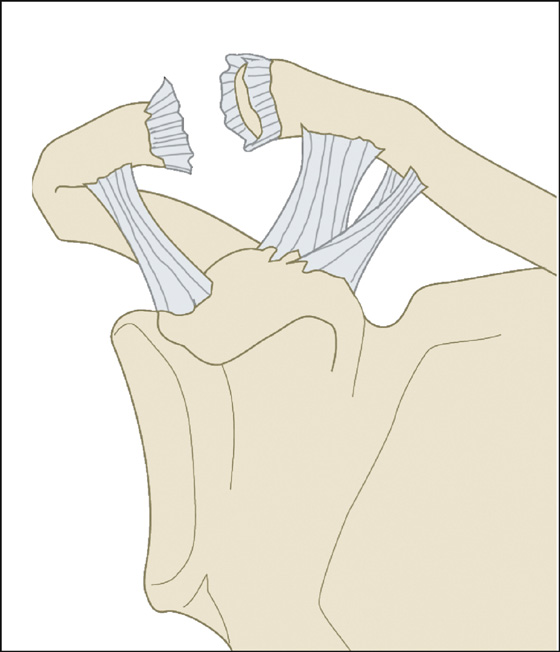

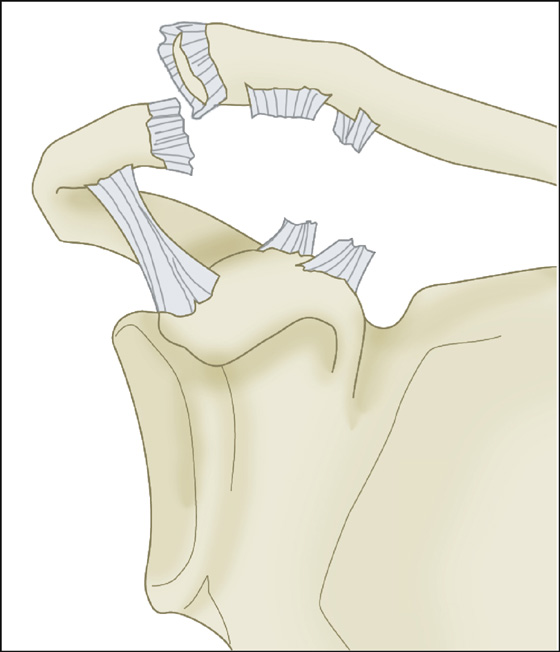

There may be no deformity, there may be a step-off between the acromion process of the scapula and the distal end of the clavicle, or the distal clavicle may be displaced superiorly and no longer connected to the acromion (Figure 96-2). These findings roughly correspond to a type I, type II (Figure 96-3), or type III (Figure 96-4) disruption of the AC joint.

Figure 96-2 Step-off deformity of grade III injury. (Adapted from Knoop KJ, Stack LB, Storrow AB: Atlas of emergency medicine. New York, 1997, McGraw-Hill.) (Courtesy Frank Birinyi, MD.)

Figure 96-3 Type II injury with rupture of the AC ligament. (Adapted from Montellese P, Dancy T: The acromioclavicular joint. Prim Care 31:857-866, 2004.)

Figure 96-4 Type III injury with rupture of the AC and coracoclavicular ligaments. (Adapted from Montellese P, Dancy T: The acromioclavicular joint. Prim Care 31:857-866, 2004.)

Usually, the patient will come in right away because it hurts even without movement (type I or type II tear), or he may come in days later without pain, having noted that the injured shoulder hangs lower or the clavicle rides higher (type III) (see Figure 96-2). There is a 5:1 male to female injury rate.

What To Do:

Provide analgesia as needed (acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], and/or narcotics).

Provide analgesia as needed (acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], and/or narcotics).

Palpate the entire shoulder girdle, including the head of the humerus. There should be tenderness only over the AC joint with varying prominence of the distal clavicle, depending on the severity of the injury. Gentle passive rotation of the humerus should not cause more pain, but there should be pain with the cross-body adduction test. This is done by elevating the arm on the affected side to 90 degrees of forward flexion and then adducting it passively as far as possible. Pain localized over the AC joint is a positive cross-body adduction test. (It is not necessary to do this test when there is an obvious deformity.)

Palpate the entire shoulder girdle, including the head of the humerus. There should be tenderness only over the AC joint with varying prominence of the distal clavicle, depending on the severity of the injury. Gentle passive rotation of the humerus should not cause more pain, but there should be pain with the cross-body adduction test. This is done by elevating the arm on the affected side to 90 degrees of forward flexion and then adducting it passively as far as possible. Pain localized over the AC joint is a positive cross-body adduction test. (It is not necessary to do this test when there is an obvious deformity.)

Examine the patient for a possible sternoclavicular joint dislocation or clavicle fracture by palpating over the entire length of the clavicle.

Examine the patient for a possible sternoclavicular joint dislocation or clavicle fracture by palpating over the entire length of the clavicle.

Strength may be decreased because of pain, but other bones, joints, range of motion, sensation, and circulation should be documented as being intact. Evaluation for neurologic injury is important because of the close proximity of the brachial plexus.

Strength may be decreased because of pain, but other bones, joints, range of motion, sensation, and circulation should be documented as being intact. Evaluation for neurologic injury is important because of the close proximity of the brachial plexus.

Obtain a radiograph of the shoulder to be sure that there is no associated fracture of the lateral clavicle or coracoid, or fracture or dislocation of the humerus. Routine AC joint radiographs include anteroposterior (AP), 10-degree caudal tilt, and axillary views (to determine the position of the clavicle with respect to the acromion). Comparison views may be useful to allow measurements of the coracoclavicular distance and distal clavicle position in the unaffected AC joint. Weight-bearing stress views are uncomfortable and unnecessary.

Obtain a radiograph of the shoulder to be sure that there is no associated fracture of the lateral clavicle or coracoid, or fracture or dislocation of the humerus. Routine AC joint radiographs include anteroposterior (AP), 10-degree caudal tilt, and axillary views (to determine the position of the clavicle with respect to the acromion). Comparison views may be useful to allow measurements of the coracoclavicular distance and distal clavicle position in the unaffected AC joint. Weight-bearing stress views are uncomfortable and unnecessary.

In a type I injury, the AC ligaments are sprained but intact. The coracoclavicular ligaments are intact, and the distal clavicle is stable and in normal anatomic alignment. In a type II injury, the AC ligaments are torn. The coracoclavicular ligaments are sprained but intact, and the distal clavicle is mobile in the axial plane with less than 50% subluxation.

In a type I injury, the AC ligaments are sprained but intact. The coracoclavicular ligaments are intact, and the distal clavicle is stable and in normal anatomic alignment. In a type II injury, the AC ligaments are torn. The coracoclavicular ligaments are sprained but intact, and the distal clavicle is mobile in the axial plane with less than 50% subluxation.

Type I and II injuries are treated the same and differ only in the time to recovery. Provide analgesics and a sling, as needed, to provide pain relief. As quickly as tolerated, the patient should begin active range-of-motion exercises. Once the range of motion is full and pain free, the performance of progressive strengthening and activity-specific exercises will prove that the patient is capable of returning to activity successfully and safely. This is variable and may take 2 to 12 weeks of rest and rehabilitation. With return to play, some football players may place a soft felt cut-out pad (doughnut pads or spider pads) in their shoulder pads to reduce the pain from a potential second impact.

Type I and II injuries are treated the same and differ only in the time to recovery. Provide analgesics and a sling, as needed, to provide pain relief. As quickly as tolerated, the patient should begin active range-of-motion exercises. Once the range of motion is full and pain free, the performance of progressive strengthening and activity-specific exercises will prove that the patient is capable of returning to activity successfully and safely. This is variable and may take 2 to 12 weeks of rest and rehabilitation. With return to play, some football players may place a soft felt cut-out pad (doughnut pads or spider pads) in their shoulder pads to reduce the pain from a potential second impact.

Type III injuries involve disruption of the acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligaments, resulting in an unstable joint. There is a 25% to 100% displacement of the AC joint. The distal clavicle is mobile in the axial and coronal planes. These are the injuries referred to in the older literature as AC dislocations.

Type III injuries involve disruption of the acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligaments, resulting in an unstable joint. There is a 25% to 100% displacement of the AC joint. The distal clavicle is mobile in the axial and coronal planes. These are the injuries referred to in the older literature as AC dislocations.

Treatment of type III injuries remains controversial. The evidence suggests that conservative therapy is the initial treatment of choice, and that surgery should be reserved for patients who have chronic pain and weakness. Conservative treatment is performed exactly as outlined for type I and II injuries, but the return to play or full activity will most likely be slower. Orthopedic referral should take place within 7 to 10 days or sooner if possible.

Treatment of type III injuries remains controversial. The evidence suggests that conservative therapy is the initial treatment of choice, and that surgery should be reserved for patients who have chronic pain and weakness. Conservative treatment is performed exactly as outlined for type I and II injuries, but the return to play or full activity will most likely be slower. Orthopedic referral should take place within 7 to 10 days or sooner if possible.

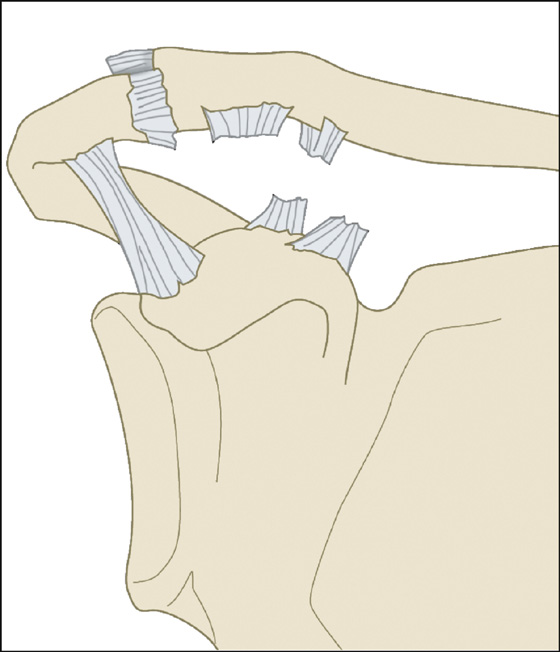

Type IV injuries (Figure 96-5) include the previous findings, and, in addition, the distal clavicle tears the deltotrapezius fascia, remaining fixed posteriorly. In type V injuries, there is a 100% to 300% joint displacement and tearing of the deltotrapezius fascia. In rare type VI injuries, the clavicle is fixed beneath the acromion or coracoid and is usually accompanied by a neurologic deficit.

Type IV injuries (Figure 96-5) include the previous findings, and, in addition, the distal clavicle tears the deltotrapezius fascia, remaining fixed posteriorly. In type V injuries, there is a 100% to 300% joint displacement and tearing of the deltotrapezius fascia. In rare type VI injuries, the clavicle is fixed beneath the acromion or coracoid and is usually accompanied by a neurologic deficit.

Figure 96-5 Type IV injury with posterior displacement of the distal clavicle. (Adapted from Montellese P, Dancy T: The acromioclavicular joint. Prim Care 31:857-866, 2004.)

Type IV, V, and VI injuries require early orthopedic consultation.

Type IV, V, and VI injuries require early orthopedic consultation.

Prescribe NSAIDs and narcotic analgesics as needed.

Prescribe NSAIDs and narcotic analgesics as needed.

For type I, II, and III injuries, arrange for reevaluation by an orthopedic surgeon and for physical therapy to begin shoulder range-of-motion exercises within 7 to 10 days.

For type I, II, and III injuries, arrange for reevaluation by an orthopedic surgeon and for physical therapy to begin shoulder range-of-motion exercises within 7 to 10 days.

What Not To Do:

Do not confuse the deformity of a displaced AC ligament tear with a dislocated shoulder, which is accompanied by loss of the normal deltoid convexity and inability to rotate the shoulder internally and externally at the side.

Do not confuse the deformity of a displaced AC ligament tear with a dislocated shoulder, which is accompanied by loss of the normal deltoid convexity and inability to rotate the shoulder internally and externally at the side.

Do not bother with weight-bearing radiographs to differentiate separations based on the widening of the distance between the clavicle and scapula. These views are painful and inaccurate.

Do not bother with weight-bearing radiographs to differentiate separations based on the widening of the distance between the clavicle and scapula. These views are painful and inaccurate.

Do not try to tape or strap the clavicle and scapula back into position. Patients have suffered ischemic necrosis of the skin from overzealous strapping. This includes the use of a Kenny-Howard sling.

Do not try to tape or strap the clavicle and scapula back into position. Patients have suffered ischemic necrosis of the skin from overzealous strapping. This includes the use of a Kenny-Howard sling.

Do not allow the patient to wear a sling and immobilize the shoulder for more than a week to 10 days without at least beginning pendulum exercises. The shoulder capsule may contract and restrict the range of motion.

Do not allow the patient to wear a sling and immobilize the shoulder for more than a week to 10 days without at least beginning pendulum exercises. The shoulder capsule may contract and restrict the range of motion.

Discussion

The AC joint is a diarthrodial synovial joint of the acromion and the distal clavicle with an intra-articular disk. This disk degenerates rapidly, resulting in narrowing of the joint space by age 40 years. The clavicle is the last bone in the body to ossify the physes; therefore Salter-Harris injuries can occur up to the age of 25 years.

The static stabilizers are the ligaments, but significant functional stability arises from the muscles attached to the shoulder girdle as well. The AC ligaments, which are incorporated into the AC joint capsule, provide most of the resistance to anteroposterior displacement and rotation of the clavicle. The two coracoclavicular ligaments, the conoid and trapezoid, prevent superior displacement of the distal clavicle. The dynamic stabilizers are the deltoid and trapezius muscles.

In patients with open physes, the physis is the weak link in the AC joint. When injured, the physis fractures and the metaphysis tears through the superior aspect of the periosteum. Because the AC joint remains in its anatomic position but the metaphysis is displaced, these injuries are called pseudodislocations. Because the inferior slip of periosteum remains in its original position, the bone it lays down is in the original orientation. Once the fracture gap is bridged, remodeling occurs, which usually brings the clavicle to its original position. Treatment for type I or III injuries is usually conservative and is the same as that described for AC joint separations.

A partial tear of the ligaments between acromion and clavicle produces pain but no widening of the joint (first-degree separation). A second-degree AC separation is visualized on radiographs as a widened joint but is otherwise the same on examination and treatment. In a third-degree or complete separation, the ligament from the coracoid process to the clavicle is probably also torn, allowing the collarbone to be pulled superior by the sternocleidomastoid muscle, but often relieving the pain of the stretched AC joint.

Nearly all patients with grade I and 90% of those with grade II injuries recover fully after 10 to 14 days of simple sling immobilization. The patient should avoid heavy lifting for 8 to 12 weeks and be referred to an orthopedic surgeon for any problems with pain or diminished range of motion.

Long-term shoulder joint stability and strength after a grade III tear remain almost normal, but patients may desire surgical repair to regain the appearance of the normal shoulder or the last few percents of function for athletics, even after being informed of the known surgical risks. Some of the literature on the treatment of AC separations listed visual prominence as a possible indication for surgery. This may be a consideration for thin patients who may have compromise of the skin or in patients who put excessive direct pressure on the AC joint, such as soldiers carrying backpacks. Caution is advised prior to surgical intervention for a cosmetic deformity, however. The surgical risks have been documented in the literature and include infection, hardware migration, failure to maintain a reduction, and scarring from the procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree