Links: Venipuncture | Peripheral IV / Capillary | U/s Guided & PICC | Umbilical Lines | Venous Cutdown | Arterial Lines | Central Lines | Vascular Anatomy | EJ | IJ | SC | PA Cath | Pulmonary & Cardiac Parameters | PA Cath Patterns | CVP | Catheter Sizes & Flushing | Complications: Infection & Clots | Catheter Infection / Sepsis | Hypodermoclysis/ Other | Implantable Devices (Ports) | Interosseous Line | Sedation | Placement | See IV / IO Access |

Intravascular lines are indicated when access to the venous or arterial circulations is necessary.

Flow rates through typical peripheral venous cannulae:

Gauge Flow (ml/min)

23 16.

21 21.

18.5 48.

16 121.

14 251.

Venipuncture:

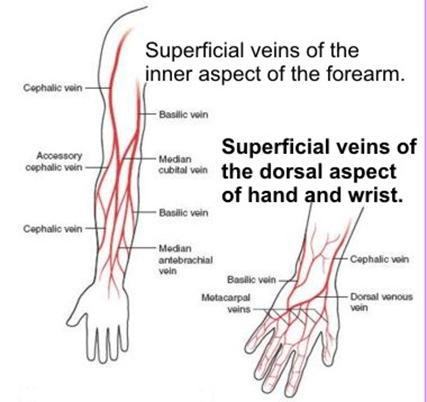

Allows procurement of larger quantities of blood for testing. Usually, the antecubital veins are the veins of choice because of ease of access. Blood values remain constant no matter which venipuncture site is selected, so long as it is venous and not arterial blood.

Step #1: Position and tighten a tourniquet on the upper arm to produce venous congestion. A blood pressure cuff can be inflated to a point between systolic and diastolic pressure values can be used.

Step #2: Ask the pt to close the fist in the designated arm. Select an accessible vein. Look for the faint bluish color of a vein under the skin, or better yet, feel for a vein with the tip of the index finger. Carefully palpate the arm 2 or 3 times if necessary. A vein suitable for venipuncture may be obscured (eg, by hair) and may therefore be missed on initial examination. Occasionally, slapping repeatedly over the vein with the pads of the first and second fingers will help to distend a faint vein, or the pt can dangle the arm over the side of the bed to achieve the same result. Do not thrust blindly at a bluish mark on the pt’s arm without first palpating the area to confirm that a patent vein is underneath. Cleanse the puncture site and dry it properly with sterile gauze. Povidone-iodine must dry thoroughly.

Step #2: Ask the pt to close the fist in the designated arm. Select an accessible vein. Look for the faint bluish color of a vein under the skin, or better yet, feel for a vein with the tip of the index finger. Carefully palpate the arm 2 or 3 times if necessary. A vein suitable for venipuncture may be obscured (eg, by hair) and may therefore be missed on initial examination. Occasionally, slapping repeatedly over the vein with the pads of the first and second fingers will help to distend a faint vein, or the pt can dangle the arm over the side of the bed to achieve the same result. Do not thrust blindly at a bluish mark on the pt’s arm without first palpating the area to confirm that a patent vein is underneath. Cleanse the puncture site and dry it properly with sterile gauze. Povidone-iodine must dry thoroughly.

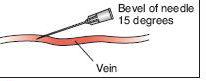

Step #3: Puncture the vein according to accepted technique. Usually, for an adult, anything smaller than a number 21-gauge needle might make blood withdrawal somewhat more difficult. A vacutainer system syringe or butterfly system may be used. Grasp the syringe or Vacutainer in the dominant hand while palpating the vein with the index finger of the other hand. Exert traction on the vein by pulling distally (toward the operator) on the skin next to the puncture site. Align the needle with the course of the vein, and make sure that the bevel is facing up. With a quick but smooth motion, push the needle through the skin at an angle of about 10-20 degrees. Then carefully advance the needle into the lumen of the vein with a smooth motion. If venous blood is not obtained on the first attempt, reassess the course of the vein. Try palpating the vein proximal to the needle site. Withdraw the needle to just below the skin, and attempt a second venipuncture.

Step #3: Puncture the vein according to accepted technique. Usually, for an adult, anything smaller than a number 21-gauge needle might make blood withdrawal somewhat more difficult. A vacutainer system syringe or butterfly system may be used. Grasp the syringe or Vacutainer in the dominant hand while palpating the vein with the index finger of the other hand. Exert traction on the vein by pulling distally (toward the operator) on the skin next to the puncture site. Align the needle with the course of the vein, and make sure that the bevel is facing up. With a quick but smooth motion, push the needle through the skin at an angle of about 10-20 degrees. Then carefully advance the needle into the lumen of the vein with a smooth motion. If venous blood is not obtained on the first attempt, reassess the course of the vein. Try palpating the vein proximal to the needle site. Withdraw the needle to just below the skin, and attempt a second venipuncture.

Step #4: Once the vein has been entered by the collecting needle, blood will flow back into the needle when the plunger is pulled away from the needle or when the Vacutainer tube is pushed onto the needle. Blood will fill the attached vacuum tubes automatically because of negative pressure within the collection tube. Remove the tourniquet before removing the needle from the puncture site or bruising will occur.

Step #5: Remove needle. Apply pressure and sterile dressing strip to site.

Note: The preservative or anticoagulant added to the collection tube depends on the test ordered. In general, most hematology tests use ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) anticoagulant. Even slightly clotted blood invalidates the test and the sample must be redrawn.

Common Errors: Failure to check pt compliance with dietary restrictions. Failure to calm pt before blood collection. Using wrong equipment and supplies. Inappropriate method of blood collection. Failure to dry site completely after cleansing with alcohol. Inserting needle with bevel side down. Using too small a needle, causing hemolysis of specimen. Venipuncture in unacceptable area (above an IV line). Prolonged tourniquet application. Wrong order of tube draw. Failure to immediately mix blood collected in additive-containing tubes. Pulling back on syringe plunger too forcefully. Failure to release tourniquet before needle withdrawal. Failure to apply pressure immediately to venipuncture site. Vigorous shaking of anticoagulated blood specimens. Forcing blood through a syringe needle into tube. Mislabeling of tubes. Failure to label specimens with infectious disease precautions as required. Failure to put date, time, and initials on requisition. Hematomas can be prevented by use of proper technique (not sticking the needle through the vein), release of the tourniquet before the needle is withdrawn, application of sufficient pressure over the puncture site, and maintenance of an extended extremity until bleeding stops. Children who were distracted by television rather than by their mothers during venipuncture reported less pain (Arch Dis Childhood. 2006;91:1015-1017). Lab test results using blood drawn from saline lock devices appear to be accurate (Acad Emerg Med 2007;14:23-7).