Abuse

34-1 Child Abuse

Charles Felzen Johnson

Child abuse (CA) is defined as intentional injuries to children that are significant or threatening to the child’s physical or psychological welfare. From a medical standpoint, an impact that results in a bruise, fracture, or damage to an internal organ should be considered significant. The failure to protect a child from injury is reportable as safety neglect. Physicians are among the mandated reporters of suspected CA.

Clinical Presentation

Intentional injuries may include such things as inflicted caustic or thermal burns, fractures, impact injuries from various objects (most commonly the hand), and acceleration-deceleration injuries to the head.1 In addition, children may be pinched, strangled, punctured, smothered, or shaken by caretakers. Children may be burned in hot water in the process of bathing, either intentionally or if the water temperature is not checked (safety neglect). Caretakers who intentionally injure a child rarely indicate this fact when they bring the child to the emergency department, and a variety of plausible, implausible, and changing explanations may be offered.1

Diagnosis

A thorough history that includes the cause, timing, treatment of, and witnesses to the injury should be obtained. Potential victims of CA should be examined thoroughly, including skin, mucosa, and the fundus. Bruises, the

most common consequence of intentional injury, change color over time, but the time course is unreliable. Familiarity with the patterns made on the skin by various common materials aids the physician in recognizing CA. Hand prints or instruments may be outlined or silhouetted on the skin.1

most common consequence of intentional injury, change color over time, but the time course is unreliable. Familiarity with the patterns made on the skin by various common materials aids the physician in recognizing CA. Hand prints or instruments may be outlined or silhouetted on the skin.1

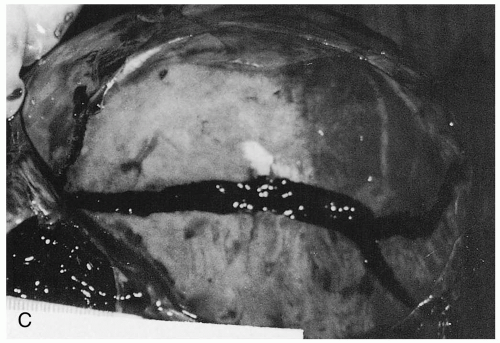

The shaken infant may present in various stages of central nervous system dysfunction, and meningitis may be suspected. Investigation may reveal subdural hematomas, bloody spinal fluid (often misinterpreted as iatrogenic), or retinal hemorrhages (85% of shaken infants).1 Because there may be a combination of shaking and impact, the term “intentional head injury” is preferred.

Clinical Complications

Complications relate to the individual injury and the delay before seeking medical attention.

Management

If the injury and the cause are not compatible, then a suspected CA report should be made to local children’s protective services or law enforcement agencies or both. This is best accomplished through the use of standardized forms. Children younger than 2 years of age with intentional trauma should have a skeletal survey and possibly a computed tomogram of the head. The accident scene and home should be investigated. All witnesses should be interviewed. Other children in the home of the injured child should be examined.1

REFERENCES

1. Johnson CF. Inflicted injury versus accidental injury. Pediatr Clin North Am 1990;37:791-814.

34-2 Shaken Baby Syndrome

Michael Greenberg

Clinical Presentation

Patients with shaken baby syndrome (SBS) present with a spectrum of problems, which depend on the time since shaking as well as the degree and severity of the shaking event. After minimal shaking, some patients have no clinically evident problems. Others present with lethargy, feeding problems, vomiting, and irritability. Severely shaken patients may present with seizures, coma, or death, sometimes with opisthotonos and distended fontanelles.1,2,3,4

Pathophysiology

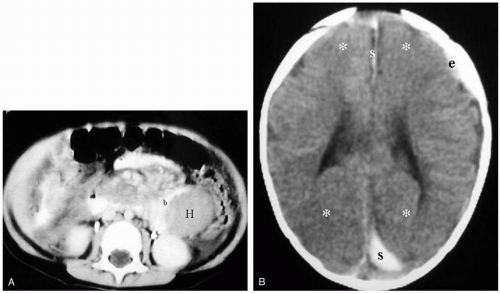

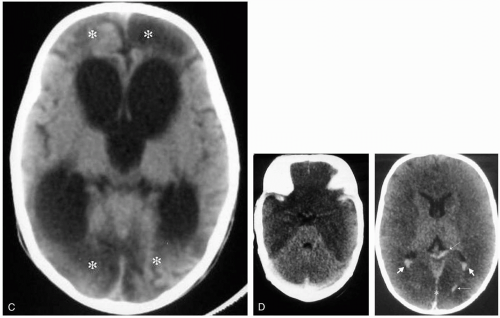

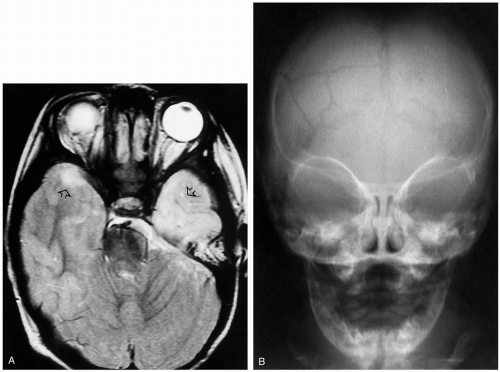

The primary injury-inducing forces involve rotational (as opposed to translational) forces transmitted to the head and brain.4 These rotational forces are generated by shaking the child and result in the brain’s moving about its central axis and at the brainstem. This causes stretching and tearing of the bridging veins between the dural venous sinuses and the cortex.4 As a result, small amounts of blood may seep into the subdural space, thus providing definite evidence of injury induced by shaking. Forceful shaking also induces diffuse axonal injury. In addition, forceful shaking results in brain tissue hypoxia, cerebral edema, and elevations in intracranial pressure.1,2,3,4

Shaken infants often manifest ocular as well as bony injuries. As many as 95% of babies with intracranial injury not associated with high-speed trauma are victims of shaking.4

Diagnosis

The key to diagnosis is the maintenance of a high index of suspicion. Physicians must never accept illogical explanations for intracranial or other injuries. Retinal hemorrhages confirm the diagnosis of SBS. Plain skull radiographs may be necessary but in general do not confirm the diagnosis of SBS. Computed tomography without contrast is often the first study done in these cases. However, magnetic resonance imaging with diffusionweighted sequences is currently considered to be the most sensitive imaging study for SBS diagnosis.1,2,3,4

Clinical Complications

Complications include bilateral or unilateral retinal hemorrhages, coagulopathies, metaphyseal fractures caused by flailing of the limbs during shaking, posterior rib fractures caused by pressure from holding the child during shaking, subdural hematomas, blindness, microcephaly, permanent brain damage, and death.1,2,3,4

Management

Emergency treatment first addresses the standard ABCs of resuscitation (airway, breathing, and circulation), monitoring, and control of intracranial pressure. If there is a suspicion of shaking, the child should be admitted to a pediatric facility. Social and law enforcement officials should be involved in the case at the earliest appropriate time.

REFERENCES

1. Morad Y, Kim Y, Mian M, et al. Nonophthalmologist accuracy in diagnosing retinal hemorrhages in the shaken baby syndrome. J Pediatr 2003;142:431-434.

2. Tsao K, Kazlas M, Weiter JJ. Ocular injuries in shaken baby syndrome. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2002;42:145-155.

3. King WJ, MacKay M, Sirnick A, Canadian Shaken Baby Syndrome Group. Shaken baby syndrome in Canada: clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospital cases. CMAJ 2003;168:155-159.

4. Blumenthal I. Shaken baby syndrome. Postgrad Med J 2002;78:732-735.

34-3 Skeletal Survey in Physical Abuse

Evan Geller

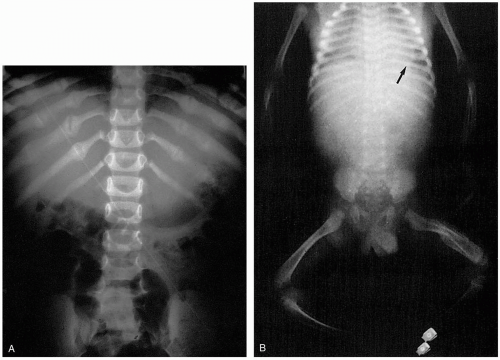

The skeletal survey should be the initial imaging study in children younger than 2 years of age who are suspected victims of nonaccidental injury.1 The skeletal survey should include the following projections:

Humerus, radius/ulna, wrist, and hand (anteroposterior [AP])

Femur, tibia/fibula, ankle, and foot (AP)

Chest, including thoracic spine and ribs (AP and lateral [LAT])

Abdomen to include lumbosacral spine and bony pelvis (AP)

Lumbosacral spine (LAT)

Cervical spine (AP and LAT)

Skull (AP and LAT)

The goal of the survey is to identify fractures that are not clinically evident as a sign of past abuse. The value of the skeletal survey as a screening study for physical abuse diminishes beyond 2 years of age and is of little utility in children older than 5 years of age.1

Diagnosis

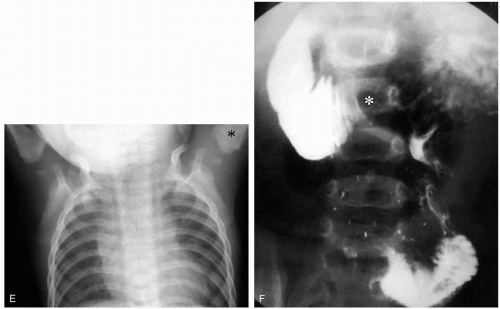

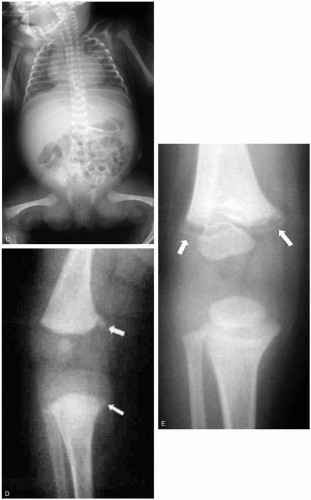

Findings on the skeletal survey may be classified according to their specificity for physical abuse. Highspecificity lesions include the following: (1) rib fractures, especially of the posterior ribs; (2) metaphyseal “corner” or “bucket-handle” fractures of the long bones; and (3) fractures of the sternum, scapulae, or spinous processes (the 3 S’s); these bones require a great force to fracture. Examples of high specificity lesions are given in Figure 34-3D,E.

Lesions of moderate specificity include (1) fractures in different stages of healing; (2) fracture of the femur/tibia in a nonambulating child; (3) complex skull fractures (e.g., depressed, stellate); and (4) digital fractures. Lesions of low specificity include (1) fracture of the femur/tibia in an ambulating child and (2) nondisplaced, linear skull fracture.

Management

If a fracture of a long bone is suspected on a single view, it is important to obtain an additional view of the injured segment. A “babygram” (Fig. 34-3C) is not an acceptable alternative to a properly performed skeletal survey, because geometric distortion and underexposure or overexposure may obscure subtle injuries. If multiple fractures are discovered on a skeletal survey, it is important to exclude an underlying bone dysplasia (e.g., osteogenesis imperfecta) or metabolic disorder (e.g., rickets) as a potential cause. If an initial skeletal survey is normal or is inconclusive relative to the degree of clinical concern, a bone scan or follow-up skeletal survey in 2 weeks may be indicated.2 Magnetic resonance imaging

or sonography or both may be indicated in the evaluation of epiphyseal separations if these are suspected on plain films. Consultation with a pediatric radiologist should be considered.

or sonography or both may be indicated in the evaluation of epiphyseal separations if these are suspected on plain films. Consultation with a pediatric radiologist should be considered.

REFERENCES

1. Diagnostic imaging of child abuse. Pediatrics 2000;105:1345-1348.

2. Kleinman PK, Nimkin K, Spevak MR, et al. Follow-up skeletal surveys in suspected child abuse. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996;167:893-896.

34-4 Abuse-Related Head Trauma

Stephen Boos

Clinical Presentation

Patients with abusive head trauma may present with obvious signs of traumatic injury, including bruising, lacerations, or slap marks. However, head injuries may be occult, revealing few or no external signs of trauma.

Pathophysiology

A wide variety of head injuries may be inflicted during child abuse, and these injuries account for 80% of pediatric deaths due to abuse.1

Shaken baby syndrome (SBS) is an abusive head injury that occurs during vigorous shaking or by direct trauma.1 Clinical signs of brain injury may be present, including decreased mental status, neurologic deficits, seizures, and retinal hemorrhage. Other signs associated with vigorous shaking include finger-shaped bruises on the thorax and fractures of the lower-extremity long bones.1 External signs of head trauma may not be evident (50% to 75%) on visual examination.1,2 SBS is produced by acceleration/deceleration of the head that is typical during shaking in addition to blunt trauma. Shear forces and blunt injury may produce diffuse axonal injury, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and subdural hematoma.1

Diagnosis

All children with head injuries require an assessment for child abuse, including a thorough history, examination for other injuries, and evaluation of the family and social interactions. Examination of the retina is essential, because 70% to 85% of patients with SBS have retinal hemorrhage.1 If there is suspicion for abuse or evidence of SBS, a skeletal survey and/or additional radiologic/laboratory evaluation may be performed, and social services should be contacted.

An attempt should be made to match the mechanism of the injury with the physical findings. For example, in accidental falls (less than 8 feet), external signs of trauma are common, only 1% to 2% of children develop skull fractures, and few patients develop epidural hematomas.1 In contrast, victims of abuse may have no signs of external trauma, but they have a high incidence

of subdural and subarachnoid bleeding (90% to 98%).1 An exception is children younger than 2 years of age, who may develop skull fractures with smaller falls (approximately 3 feet).2

of subdural and subarachnoid bleeding (90% to 98%).1 An exception is children younger than 2 years of age, who may develop skull fractures with smaller falls (approximately 3 feet).2

Clinical Complications

Between 7% and 30% of victims of abusive head injury die, and between 30% and 50% have significant long-term cognitive/neurologic deficits.1

Management

Patients with obtundation or focal neurologic deficits require an emergency computed tomographic scan and may require airway control as well as neurosurgical consultation. An evaluation for additional acute trauma (e.g., splenic laceration) and chronic trauma (e.g., long bone or rib fractures) should be initiated.

REFERENCES

1. Case ME, Graham MA, Handy TC, et al. Position paper on fatal abusive head injuries in infants and young children. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2001;22:112-122.

2. Schutzman SA, Greenes DS. Pediatric minor head trauma. Ann Emerg Med 2001;37:65-74.

34-5 Child Abuse: Bruising

Michael Greenberg

Clinical Presentation

Pathophysiology

Bruising develops when capillaries are damaged, causing blood to leave the vascular space and enter the interstitial tissue spaces.1 The stage of hemoglobin degradation within the interstitium determines the color of the bruise at any given time.1,2 The apparent color of the bruise may be altered by the skin color and tone and by the lighting under which the bruise is observed.1,2 The object used to strike the skin often creates a “negative image” of the object “surrounded by a rim of petechiae where capillaries have been stretched and torn.”1 However, injuries that are of higher impact create a “positive image” of the object due to direct vessel rupture. Common patterned bruises in abuse include those produced by hairbrushes, slap marks, belts, cords, shoes, and sticks.1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree