Key Clinical Questions

How does peripheral blood smear aid in the diagnosis of anemia?

How do I interpret iron studies?

What are the best tests to diagnose hemolytic anemia?

How do I determine the cause of hemolytic anemia?

When should I investigate for hemoglobinopathy?

What factors suggest the need for bone marrow examination?

What is the most effective way to administer oral iron?

When and how should I use erythropoietin (EPO) in anemia of renal dysfunction or anemia of chronic disease? (How is it dosed and when should I expect a response?)

How do I distinguish primary and secondary erythrocytosis in a patient who smokes or has chronic lung disease?

When should I be concerned about carbon monoxide poisoning?

How do I manage secondary erythrocytosis?

What tests should I do to rule out a myeloproliferative disorder?

What complications can occur in patients with myeloproliferative disorders?

When is phlebotomy indicated?

How frequently should phlebotomy be performed and what are the monitoring parameters?

Is there a role for antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants in patients with a myeloproliferative disorder?

Which hemoglobinopathies are considered to be clinically significant?

How is thalasemia differentiated from iron deficiency anemia?

When should one investigate for hemoglobinopathies?

When should transfusion therapy be considered?

What are the common complications in patients with thalassemia?

What are triggers for admission in a patient with sickle cell disease?

What is appropriate hydration for acute chest syndrome or painful crisis?

What clinical presentations benefit from red blood cell transfusion or red cell exchange?

What is an appropriate transfusion threshold?

How is pain optimally managed?

What are special considerations in management of sickle cell disease in pregnancy or in labor?

What are special considerations perioperatively?

When should hydroxyurea be used?

Anemia

Anemia is one of the most common blood disorders worldwide and, in developed countries, commonly affects older adults. The primary function of a red blood cell is to deliver oxygen to the tissues. Red blood cells are made in the bone marrow and must contain adequate amounts of hemoglobin to perform this function. Normal production is dependent on the availability of the required “ingredients” (ie, iron, folic acid, vitamin B12), a normal functioning bone marrow, and erythropoietin for stimulation of red cell production. Anemia can result from defects affecting hemoglobin production, dozens of disease states, including renal impairment and chronic inflammatory conditions, and may also be caused by other external or internal factors influencing the circulatory survival of red blood cells through premature destruction or blood loss. This chapter will provide a framework for investigation in order to navigate the many diagnostic tests and treatment options.

Anemia is defined as a reduction in the number of circulating red cells that results in a hemoglobin level lower than an age- and sex-matched population (Table 173-1).

| Age or Gender Group | Hb Threshold (g/dl) |

|---|---|

| Children (0.5–5.0 yrs) | 11.0 |

| Children (5–12 yrs) | 11.5 |

| Children (12–15 yrs) | 12.0 |

| Women, nonpregnant (> 15yrs) | 12.0 |

| Women, pregnant | 11.0 |

| Men (> 15yrs) | 13.0 |

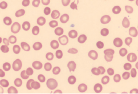

In addition to the RBC count, hemoglobin, and hematocrit, which make the diagnosis of anemia possible, the complete blood count (CBC) provides essential information that helps tailor the investigation. One of the RBC indices, the mean corpuscular volume (MCV), permits classification of hypoproliferative anemias into hypochromic microcytic anemia (MCV < 80fl), normocytic anemia (MCV 80 to 100 fl), or macrocytic anemia (MCV > 100 fl). An increase in the reticulocyte count by 1% will increase the MCV by approximately 2 fl. The red cell distribution width (RDW) reflects the variation in RBC size or anisocytosis. Useful in distinguishing between certain hypoproliferative anemias, it is normally 11.5% to 14.5%. Normally between 0.5% and 2.5%, the reticulocyte count is calculated as a percentage of the total RBC; therefore, it must be corrected in the presence of anemia. The reticulocyte production index (RPI) is one method frequently used. The RPI = % reticulocytes × (patient Hct/45)/maturation time. With increasingly severe anemia, more reticulocytes are released from the marrow. The maturation time equals 1 if the patient’s Hct is 45. Each 10-point drop in the patient’s Hct increases the maturation time by 1.5 days. A low reticulocyte count suggests an underlying defect in RBC production; an elevated reticulocyte count suggests an underlying problem in RBC survival. Likewise, a RPI less than 2.5 suggests that the anemia stems from a hypoproliferative process; a RPI greater than 2.5 suggests that the anemia is due to bleeding or hemolysis. Examination of the peripheral smear may reveal morphologic abnormalities of the RBC that permit an accurate and timely diagnosis (Table 173-2).

| RBC Size and Hemoglobin Content | Etiology | |

|---|---|---|

Hypochromic microcytic anemia with

|  |

|

Hypochromic microcytic anemia with

|  |

|

Normochromic normocytic anemia with

|  |

|

| Normochromic normocytic anemia without abnormal cells on smear |  |

|

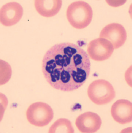

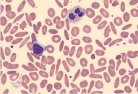

| Macrocytic anemia with hypersegmented neutrophils (one six-lobed nucleus or five-lobed nucleus in > 5% of neutrophils) |  | Megaloblastic anemia (check serum B12, serum folate, RBC folate; if all normal, BM for myedysplastic syndrome and myeloproliferative disorder) |

| Macrocytic anemia without macroovalocytes and hypersegmented neutrophils |  |

|

| Abnormal cell type | ||

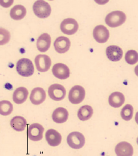

| Basophilic stippling |  | Hemolytic anemias, thalassemias, lead poisoning |

| Bite cells (Heinz bodies removed by splenic macrophages) |  | G6PD deficiency, oxidative drugs or unstable hemoglobin |

| Burr cells, spur cells (acanthocytes) |  | Liver disease, uremia, hypersplenism |

| Elliptocytes |  | Iron deficiency anemia |

| Hereditary elliptocytosis | ||

| Hemolysis of RBC |  | Hemolytic anemia |

| Howell-Jolly bodies |  | Postsplenectomy or functional asplenia |

|  | Microangiopathic or macroangiopathic hemolysis eg, DIC, TTP |

| Sickled forms |  | Sickle cell disease |

| Spherocytes (RBCs lack central pallor) |  | Immune-mediated hemolysis, hereditary spherocytosis, hypersplenism |

| Target cells |  | Thalassemias, hemoglobin C, hemoglobin E, hemoglobin S, liver disease, postsplenectomy |

| Teardrop cells |  | Myelopthisis, hypersplenism |

Although there are many causes of anemia, clinicians most commonly encounter iron deficiency anemia, thalassemia trait, and anemia of chronic disease.

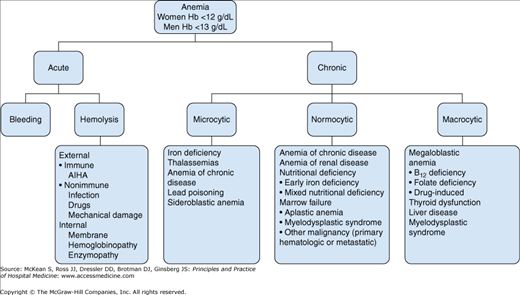

Acute anemia results from bleeding or hemolysis. In someone who has been injured or who has suffered complications of surgery, the source of acute bleeding is normally clear. Hemolysis-related anemia due to increased destruction of red blood cells occurs by various mechanisms and can be broadly categorized as intrinsic red cell defects or extrinsic processes (Figure 173-1).

Internally, problems of the red cell membrane (hereditary spherocytosis), the hemoglobin (eg, sickle cell anemia) or the deficiency of glycolytic pathway enzymes [glucose-6 phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) and pyruvate kinase (PK)] result in shorter life span. External mechanisms can be further classified as immune mediated or nonimmune resulting from infection, drugs, or mechanical injury. Hemolysis can occur intravascularly or extravascularly (ie, via the reticuloendothelial system), although many times it may be difficult to determine the site of cell destruction due to overlap in overwhelming acute cases.

The differential diagnosis of chronic anemia, whether microcytic, normocytic, or macrocytic, is broad. One of the most common causes of chronic blood loss is occult blood loss, particularly from the GI tract, or in younger women through menses, leading to iron deficiency anemia. Once the bone marrow receives the signal from erythropoietin, it requires building blocks from which to assemble the components of the red blood cell. Iron deficiency is one of the most common causes of anemia, often due to dietary deficiency or occult blood loss.

Underproduction of RBC results from a number of chronic diseases. The bone marrow, which produces the majority of red cells, relies on erythropoietin secreted by the kidneys to signal the need for new red blood cell production. In renal impairment, a decreased erythropoietin level leads to chronic anemia. In bone marrow failure states, underproduction may be caused by a decrease of precursor cells (eg, aplastic anemia, pure red cell aplasia), crowding out of normal RBC precursors by malignant cells (eg, leukemia, metastatic cancer) or abnormal maturation (eg, myelodysplastic syndrome, vitamin B12, or folate deficiency). Inflammatory conditions can also cause chronic anemia by a combination of mechanisms due to proinflammatory cytokines that produce a “functional” iron deficiency in which iron is trapped in storage (eg, inside macrophages) instead of being available for hemoglobin production, abnormal proliferation of RBC progenitors in the bone marrow, insufficient erythropoietin, and reduced RBC life span.

A complete blood count (CBC) is the backbone for the evaluation of anemia. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines anemia in an adult as a hemoglobin < 13g/dL for men and < 12 g/dL for women. A patient with chronic, mild, stable anemia can comfortably be evaluated in an outpatient setting. However, any patient with acute and/or severe anemia will benefit from the intensive investigations, monitoring, and treatment offered in the hospital. Anyone who is hemodynamically unstable due to blood loss should receive care in a monitored setting. After the diagnosis of anemia is confirmed, the next step is to determine why so that appropriate treatment can be administered (Figure 173-1).

Since the potential causes of anemia are numerous, a thorough and broad history should include query about:

- Any associated symptoms, in particular, bleeding (gastrointestinal, including melena, menses, hematuria) and constitutional B symptoms

- Past medical history, in particular, autoimmune/inflammatory disorder, chronic infection, liver disease, renal impairment, thyroid dysfunction, previous diagnosis, and treatment of anemia

- Medication history

- Social history, in particular, dietary intake, alcohol use, risk of sexually transmitted infections

- Family history of anemia

- Full review of systems, which may uncover symptoms of previously undiagnosed inflammatory disorders or organ dysfunction

Most prominent symptoms in severe anemia include fatigue, dizziness, palpitations, or breathlessness on physical exertion. Information about the onset of symptoms may help to determine whether the anemia is acute or chronic. The patient should also be questioned as to whether he or she has had a recent complete blood count.

|

The physical examination may reveal evidence of decompensation as in acute blood loss (eg, unstable vital signs) or chronic extreme anemia (eg, congestive heart failure), signs of severe anemia (eg, pallor of the skin, conjunctivae, tongue, nail beds, and palmar creases, or tachycardia and the presence of a flow murmur), or help to identify previously unknown systemic disease (eg, signs of chronic liver disease).

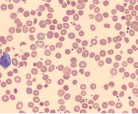

Recent blood tests showing a previously normal hemoglobin level may confirm that the anemia is acute. Elevated reticulocyte count or reticulocyte percent is suggestive of acute or ongoing blood loss or hemolysis. If the anemia is not acute, workup can be guided by the peripheral blood smear and the mean corpuscular volume (MCV) of the red blood cells—small (microcytic), large (macrocytic), or normal size (normocytic). It is also important to note the white blood cell and platelet counts. Pancytopenia can be seen in aplastic anemia, vitamin B12 deficiency, myelodysplastic syndrome, primary bone marrow malignancies, or in liver disease with portal hypertension and splenomegaly. A normal white blood cell and platelet count with isolated anemia is unlikely to be due to marrow failure, with the exception of pure red cell aplasia. The reticulocyte count may also be useful to distinguish conditions associated with hyporegenerative anemia having low values of < 50 × 109/L (aplastic anemia, pure red cell aplasia, or marrow infiltration) from a regenerative anemia seen with hemolysis or hemorrhage.

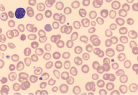

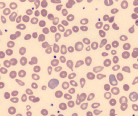

The appearance of the red cells in a peripheral blood film can be associated with the different causes of anemia, and offers suggestions for relevant subsequent investigations (Table 173-2).

|

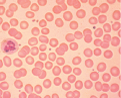

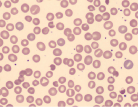

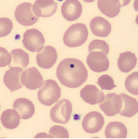

Peripheral blood smear in iron deficiency anemia (IDA) shows small (“microcytic” or low MCV) red blood cells that are very pale (“hypochromic”) containing less hemoglobin as indicated by a reduced mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH). Other changes of note may include anisocytosis (variable size of red blood cells) and poikilocytosis (variable shape of RBCs, for example target cells and pencil cells). Based on the blood smear alone it is difficult to discern IDA from a thalassemia trait. Therefore, further laboratory testing to investigate iron status and for exclusion of a possible hemoglobinopathy may be required.

Serum ferritin is considered a good measure of iron stores; levels below 30 mg/L in otherwise healthy patients are reflective of iron deficiency. However, ferritin is an acute phase reactant and may be higher in iron deficient patients with other medical problems. For this reason, the ferritin threshold may need to be increased. If the diagnosis is unclear, bone marrow examination, which is considered the “gold standard” test to confirm iron deficiency anemia, should be considered. Other tests that may be useful for the confirmation of a diagnosis in microcytic anemia include serum iron, total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), serum transferrin receptor, and measurement of zinc protoporphyrin (ZPP) and free erythrocyte protoporphyrins (FEP) (Table 173-3).

| Biochemical Marker | Iron Deficiency Anemia | Anemia of Chronic Disease/Inflammation |

|---|---|---|

| Serum ferritin | Decreased | Normal or increased |

| Serum iron | Decreased | Deceased or normal |

| Total iron-binding capacity | Normal to increased | Decreased or normal |

| Transferrin saturation | Decreased | Decreased or normal |

| Serum transferrin receptor | Increased | Normal |

| ZPP or FEP | Increased | Increased |

|

A hemoglobinopathy should be considered if the patient is healthy, not iron deficient, has a family history of microcytic anemia or thalassemia, or if the patient’s ethnic group is known to commonly have thalassemia or variant hemoglobins associated with microcytosis (Hb E). Initial hemoglobinopathy investigations will quantify normal and abnormal hemoglobins to identify beta-thalassemia trait, homozygous beta-thalassemia, and Hb E. However, further DNA analysis may be required for diagnosis of alpha-thalassemia or may be useful to confirm the presence of other globin gene deletions or mutations. Pregnant women with microcytosis should always be considered for hemoglobinopathy testing regardless of iron status due to the risk of genetic transmission of a severe form of hemoglobinopathy or thalassemia to the fetus.

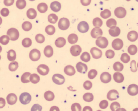

Normocytic anemia is the most frequently encountered category of anemia, and is often the most difficult to work up because it can result from many disparate disorders; it can be due to decreased RBC production, either primary (eg, aplastic anemia, acute leukemia) or secondary (eg, renal failure, anemia of chronic disease). Hemolytic anemia, both immune and nonimmune, and acute bleeding can also present as normocytic anemia.

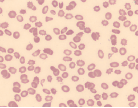

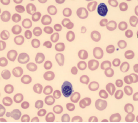

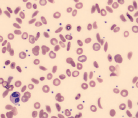

Hemolytic anemia may present in many ways; it can be acute and uncompensated or chronic and well compensated, or anything in between. Therefore most patients presenting with anemia of unclear etiology should be screened for hemolysis. The red cells in hemolytic anemia often vary in appearance depending on the underlying process. Examination of the peripheral smear is a useful tool for the differential diagnosis. Spherocytes can be present in autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) or in hereditary spherocytosis when the patient has a negative Coombs test. Sickle cell anemia manifests with characteristic sickle-shaped cells. Schistocytes are a hallmark of red cell destruction and can be correlated with platelet numbers for differentiating a microangiopathic hemolytic anemia from macroangiopathic hemolytic conditions 9 eg, caused by heart valves. Decreased platelets are seen in disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). Platelets are normal in macroangiopathic hemolytic conditions caused by heart valves.

Screening tests that suggest the possibility of hemolysis include elevated lactate dehydrogenase, elevated unconjugated bilirubin, and elevated reticulocyte count. The level of haptoglobin, a protein that binds free hemoglobin in the circulation, may be a useful indicator for hemolysis. A low level or absence of haptoglobin, along with the presence of free hemoglobin in circulation, is suggestive of hemolysis. However, low haptoglobin can also be seen in liver disease. Haptoglobins are an acute phase reactant and therefore may be falsely elevated during any inflammatory process.

Often further specialized testing is required to confirm and identify the cause of hemolytic anemia. This can include direct antiglobulin test (DAT or Coombs test), hemoglobinopathy testing, and/or enzymopathy testing, as indicated. The DAT identifies IgG and/or complement on the RBC surface and can be positive in AIHA, drug-induced anemia, or a hemolytic transfusion reaction. A hemoglobinopathy investigation separates and quantifies the expected hemoglobins (Hb A, A2, and F) but will also identify many variant hemoglobins (eg, HbS, C, or E) or other rarer unstable hemoglobin variants (eg, Hb Köln, Hb Hasharon) known to cause hemolysis. To assess for enzyme deficiencies, quantitative testing of red cell pyruvate kinase and G6PD is performed. More recently, flow cytometry has been used to identify paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) using the GPI-anchored antigens CD55 and CD59 on red cells or neutrophils. The osmotic fragility (OF) test is useful for confirmation of hereditary spherocytosis. However, the eosin-5-maleimide (EMA) dye binding test by flow cytometry has shown to have higher specificity and sensitivity than OF for red cell cytoskeleton disorders causing hemolysis.

If anemia is due to decreased RBC production, the reticulocyte count will be low or “inappropriately normal.” Serum erythropoietin level can be helpful but it is nondiagnostic; if it is high, it may indicate a primary bone marrow problem, which could be confirmed with a bone marrow aspirate and/or biopsy. Serum erythropoietin level will be low or inappropriately normal in any of the secondary causes of normocytic anemia, particularly in renal dysfunction. Moderate renal impairment can present with anemia, therefore renal function testing is essential, regardless of serum EPO level.

Anemia of chronic disease (ACD) is a difficult diagnosis to pin down. Essentially it is a clinical diagnosis in a patient who has had a sufficient and negative workup for other causes of anemia, and who has an underlying inflammatory condition. Measurement of iron indices or inflammatory markers (eg, erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein) may be a useful adjunct in testing. Bone marrow exam should reveal normal or increased amounts of stored iron and decreased iron staining in erythroid precursors, reflecting impaired iron utilization.

Vitamin B12 (also known as cobalamin) is obtained by intake of animal products, including red meat, poultry, fish, dairy, and eggs. The total body store of vitamin B12 is 2–5 mg, primarily stored in the liver. Approximately 2–5 mcg of B12 is lost daily, most of which is excreted in the bile.

Although a typical Western diet contains 5–20 mcg/day of vitamin B12, which is more than sufficient to replace daily losses, B12 deficiency can occur in individuals following a strict vegan diet.

In patients with gastritis, gastric atrophy, or history of gastrectomy, absence of gastric acid and pepsin prevents release of cobalamin from the protein to which it is bound. Furthermore, production of gastric intrinsic factor (IF), a molecule that binds free cobalamin in the gastrointestinal tract and facilitates cobalamin absorption in the terminal ileum, may be impaired. Malabsorption can also occur if there is inadequate absorption at the terminal ileum, due to prior resection or Crohn’s disease.

One of the most common causes of B12 deficiency is pernicious anemia, in which there is a deficiency of IF due to presumed autoimmune destruction of gastric parietal cells or the IF itself.

Vitamin B12 deficiency presents most commonly with hematologic abnormalities and/or neuropsychiatric signs and symptoms. Macrocytic anemia, with macro-ovalocytes on peripheral blood smear, is the classic hematologic abnormality. Neutrophils have hypersegmented nuclei. There may also be leukopenia and/or thrombocytopenia. Bone marrow examination reveals megaloblastosis.

The classic neurological manifestation is subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord, resulting in sensory and motor disturbances that cause ataxia. Peripheral and cranial neuropathies may also be seen. In severe cases, patients may present with stroke or dementia-like syndromes. Physical exam may reveal classic findings such as glossitis and jaundice.

A serum B12 level < 200ng/L (148pmol/L) is very sensitive (97%) for the diagnosis of B12 deficiency. Because some patients with normal or low-normal serum B12 levels may be truly deficient and benefit from vitamin replacement, elevated methylmalonic acid (MMA) and homocysteine can help to clarify the diagnosis. Elevated MMA and hemocysteine are both sensitive early markers of B12 deficiency. Elevated levels should, however, be interpreted in the context of individual patients: homocysteine is also elevated in folate deficiency and hereditary homocyteinemia. MMA may be elevated in renal insufficiency and methylmalonic aciduria, and in some patients with folate deficiency. Serum MMA may be lowered in B12-deficient patients receiving antibiotic treatment. A Schilling test, involving oral administration of radiolabeled cocyanocobalamin, has historically been used to assess vitamin B12 absorption. Unfortunately, the Schilling test is not widely available. Anti-intrinsic factor antibodies are highly specific for pernicious anemia (specificity > 95%) and therefore, if positive, help to confirm the diagnosis; however sensitivity is poor (50–70%).

Folate is found in animal products and leafy green vegetables. As such, the most common cause of folate deficiency is inadequate nutritional intake. With universal folate supplementation, folate deficiency has become increasingly rare. However, patients with alcohol abuse remain at risk due to folate malabsorption and impaired folate metabolism in the liver. Individuals with increased folate requirements are also at increased risk. This includes pregnant women (for whom folate deficiency is associated with an increased risk of fetal spina bifida) and patients with chronic hemolytic anemia. The widespread use of routine, prophylactic folic acid supplementation in these groups can prevent deficiency. Use of some drugs has been linked to folate deficiency, including trimethoprim, pyrimethamin, methotrexate, and phenytoin.

Similar to vitamin B12 deficiency, folate deficiency can result in megaloblastic anemia. However, folate deficiency has no neurologic sequelae.

Diagnosis is made when the serum or red blood cell folate is below the normal range. Serum folate concentration may be normal in approximately 5% of individuals with folate deficiency; therefore if there is still a high index of suspicion, red blood cell folate should be tested.

A number of drugs can cause macrocytosis or macrocytic anemia. These include the following:

- Pyrimidine and purine analogs that inhibit DNA synthesis (eg, 5-FU, azathioprine)

- Antifolates (eg, methotrexate)

- Hydroxyurea

- Zidovudine

Occasionally, an exceptionally brisk reticulocytosis in response to anemia results in the average red blood cell being larger, thus increasing the MCV measurement. Other causes of macrocytosis that should be considered include liver disease, hypothyroidism, alcohol abuse, and myelodysplastic syndrome.

|

The goal of treatment for IDA is to improve the hemoglobin level and replenish iron stores. This typically requires 150–200 mg elemental iron per day for four to six months, or until serum ferritin has increased to approximately 50 mg/L. Iron is given orally unless the patient has severe gastrointestinal intolerance, malabsorption, or uncontrolled blood loss. The relative amounts of elemental iron in different preparations are listed below:

| Ferrous gluconate: | 300 mg | 35 mg elemental iron |

| Ferrous sulfate: | 300 mg | 60 mg elemental iron |

| Ferrous fumarate: | 300 mg | 100 mg elemental iron |

| Polysaccharide iron complex: | 150 mg | 150 mg elemental iron |

In the absence of ongoing blood loss, hemoglobin should increase by 1–2 g/dL within three weeks of starting adequate oral replacement, and iron stores should be replete in three months. Failure to respond may be due to nonadherence, poor iron absorption, or an incorrect diagnosis. If instead the patient has thalassemia, iron supplementation could be harmful, in that it will increase iron overload.

To improve iron absorption, the iron tablets should be taken on an empty stomach or with orange juice or a tablet of ascorbic acid. Concurrent administration of antacids should be avoided. Many patients complain of nausea or dyspepsia 30–60 minutes following a dose. This often subsides with ongoing treatment but, if it is an ongoing issue, night time dosing or administration of higher doses with food may improve symptoms and maintain adequate absorption.

Intravenous iron is an option for patients who are intolerant of or who do not respond to oral iron. These must be administered in a medically supervised area because of risks of hypotension, allergic, or anaphylactic reactions. Several iron preparations are available for intravenous administration, of which iron dextran has the highest risk of adverse reactions.

Vitamin B12 replacement can be divided into initial management (designed to quickly build up the tissue stores) and long-term maintenance treatment. A common initial regimen consists of intramuscular cyanocobalamin 1000 mcg/day for one or two weeks, followed by 1000 mcg/week for one month. Hematologic response should be evident one week after the first dose. In particular, there should be a noticeable increase in the reticulocyte count. If reticulocytosis is mild or absent, the original diagnosis should be questioned. By the eighth week, the MCV should have returned to the normal range.

Maintenance treatment can be given parenterally or orally. Parenteral cyanocobalamin may be given at a dose of 1000 mcg/month until the cause of deficiency is corrected, or lifelong in pernicious anemia. Oral therapy for pernicious anemia is 1000 mcg/day. Lower doses (eg, 125–500 mcg/day) can be given for other causes of deficiency; however the cost and risk of a higher dose are negligible and a standard dose of 1000 mcg/day is commonly prescribed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree