ABDOMINAL PAIN

The causes of abdominal pain are myriad, but may be categorized by classical symptom complexes. As with most disorders, there are serious causes and minor disturbances. The purpose of taking a history and performing a physical examination is to determine the urgency of the situation, in order to plan for evacuation if necessary. Because differentiation between various causes is often difficult, the recommendations that follow are ultraconservative. Any person with severe abdominal pain should be seen by a physician as soon as possible.

GENERAL EVALUATION

1. Nature of the pain. Is the pain sharp (knife-like), aching (constant), colicky (intermittent and severe), or cramping (squeezing)? Has the victim ever suffered a similar episode? Been given a specific diagnosis?

2. Location of the pain. Is the pain well localized to one particular area, or does it radiate to another region (from the back to the groin, for example)? Did the pain begin in one region and move to another?

3. Mode of onset of the pain. Did the pain occur suddenly, or has it gradually increased in intensity? How long has the victim been in pain?

4. Associated symptoms. Is the victim short of breath, nauseated, vomiting, suffering from diarrhea or constipation, or dizzy? Is the victim vomiting blood, bile (green liquid produced by the gallbladder), or “coffee grounds” (blood darkened by stomach acid)? Does the vomit smell like feces?

5. Relief of pain. Is there a position that the victim can assume that will lessen the pain? Does the victim feel better in a quiet position, or is he agitated and constantly moving around?

6. Menstrual history. In the female victim, it is important to determine if there is any chance that the abdominal pain is related to a disorder of pregnancy.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Perform the following physical examination:

1. Observe the victim. Note whether he is active or avoids movement. If possible, note the severity of distress when the victim has his attention diverted (and so is not focusing all of his attention on your examination).

2. Note the victim’s skin color, pulse rate and strength, rate of respirations, effort of breathing, mental status, and temperature. Abnormalities of any of these heighten the possibility of a serious problem.

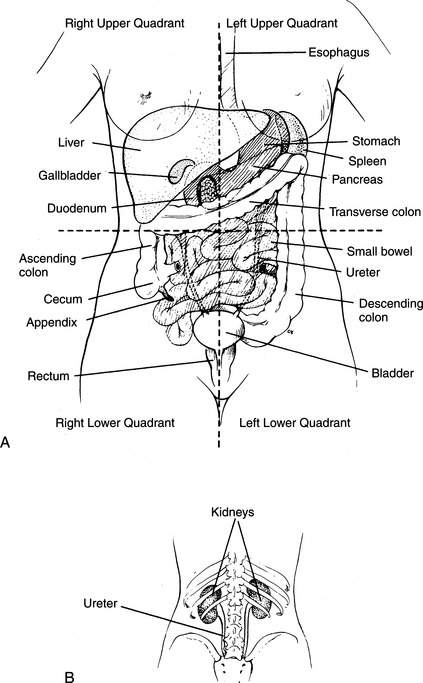

3. Examine the abdomen. This is best done by having the victim lie quietly on his back, with his knees drawn up. Gently press on the abdomen, proceeding from the area of least discomfort to the area of greatest discomfort. For the purposes of examination, the abdomen can be divided by perpendicular lines through the navel into four quadrants: right upper, left upper, right lower, and left lower (Figure 95). The epigastrium is the area of the abdomen directly below (not underneath) the breastbone in the midline. Note where the victim complains of pain and whether the pain is affected by your examination. If the victim has increased sharp pain when you suddenly release your hands from his abdomen after a pressing maneuver, this may indicate “rebound” pain associated with general inflammation of the lining of the abdominal cavity (peritonitis). Rebound pain may be caused by severe infection or leakage of blood or stomach/bowel contents into the abdominal (peritoneal) cavity, or by other problems that are generally quite severe.

When a specific area of the abdomen is tender, there are certain disorders to consider:

Epigastrium. Heart attack, ulcer, gastroenteritis, heartburn, pancreatitis.

Right upper quadrant. Injured liver, hepatitis, gallstones, pneumonia.

Left upper quadrant. Injured spleen, gastroenteritis, pancreatitis, pneumonia.

Right lower quadrant. Appendicitis, kidney stone, ovarian infection (pelvic inflammatory disease), ectopic (fallopian tube [“tubal”]) pregnancy, colitis, bowel obstruction, hernia, miscarriage, kidney stone, painful menses.

Left lower quadrant. Diverticulitis, colitis, kidney stone, ovarian infection, ectopic (fallopian tube [“tubal”]) pregnancy, bowel obstruction, hernia, miscarriage, kidney stone, painful menses.

Lower abdomen (central). Abdominal aortic aneurysm, ovarian infection, ovulation disorder, ectopic (fallopian tube [“tubal”]) pregnancy, bladder infection, colitis, bowel obstruction, inflammatory bowel disease (“irritable bowel”).

Flank. Abdominal aortic aneurysm, kidney stone, kidney infection, pneumonia.

By quadrant, brief descriptions of and treatments for these disorders follow.

EPIGASTRIUM

Ulcer (See Also Page 223)

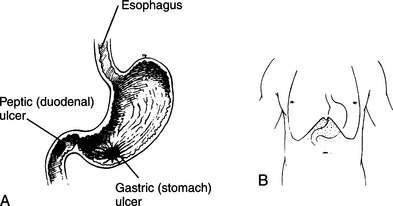

An ulcer is an erosion in the lining of the stomach (gastric ulcer) or duodenum (peptic ulcer) that penetrates the protective mucous layer and allows acid and digestive juices to erode deeper into the tissues (Figure 96). This causes extreme pain and can lead to bleeding from leaking blood vessels in the ulcer crater. Symptoms include constant burning pain in the epigastrium that is made worse by pressing and is often associated with nausea and/or belching. In a minor case, the pain may be relieved by a meal. In a severe case, when the ulcer has eroded into a blood vessel or has perforated the wall of the stomach or bowel, the victim will vomit red blood or dark brown clotted blood (“coffee grounds”) and complain of pain that may radiate to his back. Rebound tenderness and peritonitis may be present. Dark black tarry bowel movements (melena) are caused by blood that has made its transit through the bowel. Bright red blood or blood clots with a bowel movement can be caused by brisk bleeding from an ulcer, but more commonly originate from bleeding that is occurring within the large intestine (colon) or rectum, or from hemorrhoids (see page 220). Mild bleeding from an ulcer may actually transiently decrease the pain, because blood acts as an antacid. Some ulcers are caused by bacterial (usually, Helicobacter pylori) infection. To eradicate the bacteria and allow the ulcer to heal, a physician must prescribe specific, intense antibiotic therapy.

Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis is often called the “stomach flu” (see the discussion of diarrhea on page 207). Symptoms include waves of crampy upper and/or lower abdominal pain, followed by loose bowel movements. Nausea and vomiting may be present. Occasionally, the victim has symptoms of an upper respiratory infection, with cough, runny nose, sore throat, headache, and fever. The treatment for viral gastroenteritis consists of an adequate liquid diet (hydration is the key to recovery—see page 208) and medicine for intractable vomiting (see page 222). When a victim vomits green bile, this should be taken as a sign that the problem is more serious than straightforward gastroenteritis, although bilious vomiting can occur with repetitive retching, when the stomach has been emptied and duodenal contents are all that is left for regurgitation.

RIGHT UPPER QUADRANT

Injured Liver

If a fall or blow to the abdomen, right flank, or right lower chest is followed by abdominal pain that is worsened by pressing on the right upper quadrant, a torn or bruised liver should be considered. The victim is at risk for severe internal bleeding and should be observed for signs of shock (see page 60). Evacuate him as soon as possible.

Gallstones (Cholelithiasis)

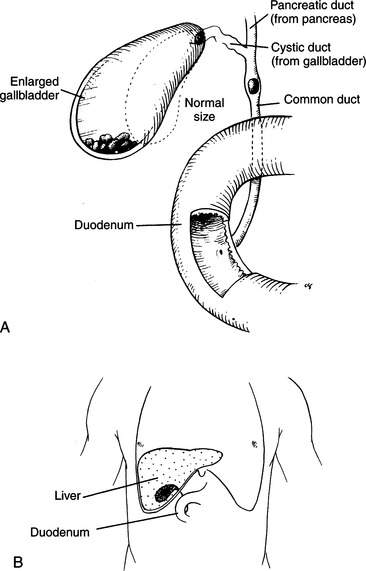

Gallstones are formed in the gallbladder, which lies under the liver in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. The gallbladder stores bile (manufactured in the liver), which is released into the duodenum to aid in digestion following each meal (Figure 97). An attack of gallbladder inflammation (cholecystitis) occurs when the outlet from the gallbladder or the main bile duct into the duodenum becomes obstructed (usually by a gallstone) and the gallbladder cannot empty. This causes stretching of the gallbladder, inflammation, and painful contraction against an impenetrable passage. There is often an element of infection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree