Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

Mudit Mathur

J. Chiaka Ejike

KEY POINTS

Intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) can be measured easily using the indirect intravesical method by creating a fluid column through saline instillation into the urinary bladder (1 mL/kg up to 25 mL, or a standard volume of 3 mL irrespective of weight) and recording the pressure across this fluid column.

Intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) can be measured easily using the indirect intravesical method by creating a fluid column through saline instillation into the urinary bladder (1 mL/kg up to 25 mL, or a standard volume of 3 mL irrespective of weight) and recording the pressure across this fluid column. Abdominal perfusion pressure (APP) appears to be a better predictor of outcome from intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) than mean arterial pressure, IAP, or other traditionally used resuscitation endpoints.

Abdominal perfusion pressure (APP) appears to be a better predictor of outcome from intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) than mean arterial pressure, IAP, or other traditionally used resuscitation endpoints. IAH and abdominal compartment syndrome can lead to multi-organ system failure and are associated with increased morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients.

IAH and abdominal compartment syndrome can lead to multi-organ system failure and are associated with increased morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients. Clinical examination is not a reliable substitute for measuring IAP.

Clinical examination is not a reliable substitute for measuring IAP. A high index of suspicion should be used in initiating serial IAP monitoring in patient populations at risk for developing IAH and abdominal compartment syndrome.

A high index of suspicion should be used in initiating serial IAP monitoring in patient populations at risk for developing IAH and abdominal compartment syndrome. Principles of medical management include treating the underlying condition, improving abdominal wall compliance, evacuating intraluminal contents, optimization of fluid balance, identification and evacuation of abdominal fluid collections, and optimizing regional and systemic perfusion.

Principles of medical management include treating the underlying condition, improving abdominal wall compliance, evacuating intraluminal contents, optimization of fluid balance, identification and evacuation of abdominal fluid collections, and optimizing regional and systemic perfusion.INTRODUCTION

Increased pressure in a confined anatomical space affects local circulation and threatens the function and viability of the organs contained within. Abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) results from a sustained pathological increase in intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) leading to organ dysfunction and failure. The term ACS was first coined by Kron et al. (1) in 1984, though the adverse effects of IAP have been known for over one hundred years. Pediatric surgeons have long recognized that staged closure of omphaloceles reduces the risk of excessive intraperitoneal tension and improves outcome of abdominal wall repair in newborns (2). ACS is an increasingly recognized complication in critically ill children with varied underlying medical and surgical pathology. Recent efforts by a multispecialty group of healthcare professionals (The World Society of Abdominal Compartment Syndrome [WSACS]) have led to the development of consensus definitions for the diagnosis and management of ACS in adults and children (3,4).

CONSENSUS DEFINITIONS

The WSACS recently released updated consensus definitions that for the first time include specific definitions applicable to children (5).

IAP is the steady-state pressure concealed within the abdominal cavity. IAP in critically ill children is approximately 4-10 mm Hg.

Intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) in children is a sustained or repeated pathologic elevation in IAP > 10 mm Hg (>12 mm Hg in adults). IAH can be classified by severity on the basis of the IAP reading: Grade I (12-15 mm Hg), Grade II (16-20 mm Hg), Grade III (IAP 21-25 mm Hg), or Grade IV (IAP > 25 mm Hg) (3). The clinical significance of grading IAH is unclear but may be useful when comparing patient populations between studies.

ACS in children is defined as a sustained elevation in IAP greater than 10 mm Hg associated with new or worsening organ dysfunction that can be attributed to elevated IAP.

ACS may be classified as primary, secondary, or tertiary, depending on its origin and the underlying condition. Primary ACS is associated with an injury or disease in the abdomen or pelvis (e.g., abdominal trauma or peritonitis). Secondary ACS originates from outside the abdomino-pelvic region (e.g., massive fluid resuscitation for septic shock). Tertiary ACS occurs when ACS redevelops after medical or surgical treatment of primary or secondary ACS.

Abdominal perfusion pressure (APP) is the mathematical difference between the mean arterial pressure (MAP) and the IAP (APP = MAP – IAP). This is analogous to the concept of cerebral perfusion pressure (6). Normative data for APP are not available for children. The threshold APP below which organ dysfunction ensues is likely to be lower in children than the 60 mm Hg value used in adults because normal MAP values are lower in children (7,8).

Clinical Interpretation of IAP Values

The consensus definitions serve as the basis for diagnosing various grades of IAP elevation in children. Elevation of IAP above normal constitutes IAH and leads to physiologic changes within the abdominal cavity and beyond. Initial effects include reduction in perfusion to abdominal organs, but can progress to affect multiple extra-abdominal organ systems if untreated. It is important to recognize that there

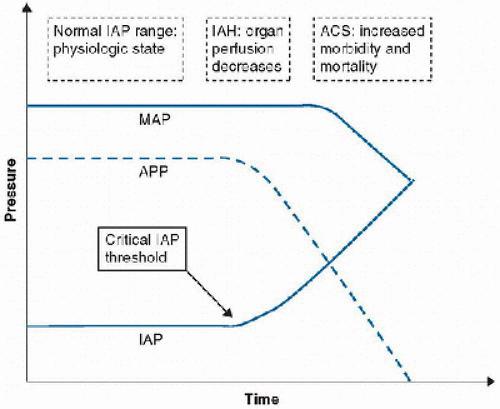

is a spectrum of IAP elevation that culminates in ACS. Early recognition and management of IAH and ACS are important to prevent progression to multisystem organ dysfunction and death (Fig. 100.1). The increase in IAP is exponential beyond a “critical IAP” threshold and leads to reduced APP, decreased organ perfusion, and end-organ injury.

is a spectrum of IAP elevation that culminates in ACS. Early recognition and management of IAH and ACS are important to prevent progression to multisystem organ dysfunction and death (Fig. 100.1). The increase in IAP is exponential beyond a “critical IAP” threshold and leads to reduced APP, decreased organ perfusion, and end-organ injury.

FIGURE 100.1. The intra-abdominal hypertension spectrum: With progression from normal IAP to IAH, APP falls and organ perfusion is compromised. If untreated, IAH may lead to ACS, increasing morbidity, and mortality. MAP, mean arterial pressure; APP, abdominal perfusion pressure; IAP, intra-abdominal pressure; IAH, intra-abdominal hypertension; ACS, abdominal compartment syndrome. |

The exact threshold beyond which IAP compromises organ perfusion may vary among patients. It may depend on comorbidities and the stage of progression of the causative pathophysiology. Thus, monitoring APP closely may be more useful than relying on the IAP values alone. Serial IAP monitoring and comprehensive medical and surgical management, using goal-directed optimization of APP, systemic perfusion, and organ function have been shown to improve survival in adults with IAH/ACS (9).

Optimal APP in the pediatric population is unknown, but is likely lower than that in adults, due to lower age-dependent MAP in infants and children (10). In a study of 585 neonates and children undergoing laparoscopy, cardiopulmonary function was affected at IAP as low as 6 mm Hg in newborns and at 12 mm Hg in older children (11). Elevated IAP in the 9-13 mm Hg range has been associated with exacerbation of necrotizing enterocolitis in newborns (12). This supports the updated definition by the WSACS with an IAP threshold for defining IAH and ACS in children that is lower than that used in adults.

TECHNIQUES FOR MEASURING IAP

IAP is measured with the patient supine, in the absence of abdominal muscle contraction, and recorded in mm Hg at endexpiration using a closed, de-bubbled system with the pressure transducer zeroed at the mid-axillary line. The techniques for measuring IAP are broadly classified into two categories.

Indirect Methods

These methods are based on measuring IAP indirectly across the walls of an intra-abdominal organ or structure. The indirect method used most commonly is the intravesical method  performed via a urinary catheter. When the bladder is drained or has a minimal volume, the IAP is transmitted through the bladder’s compliant wall and is measured by transducing the urinary catheter. A minimum volume of 3 mL or 1 mL/kg up to a maximum of 25 mL saline is instilled into the Foley catheter to establish a continuous fluid column with the pressure transducer, and IAP is recorded (10). IAP may be measured using a fluid column, in which case the reading is in cmH2O and should be converted to mm Hg by dividing by 1.36. Bladder detrusor muscle spasm may occur during saline instillation; thus, allowing time (30 seconds to 1 minute) for equilibration of pressures permits an accurate steady-state IAP to be measured (13). IAP should be expressed in mm Hg and measured at end-expiration in the supine position after ensuring that abdominal muscle contractions are absent and with the transducer zeroed at the level of the mid-axillary line.

performed via a urinary catheter. When the bladder is drained or has a minimal volume, the IAP is transmitted through the bladder’s compliant wall and is measured by transducing the urinary catheter. A minimum volume of 3 mL or 1 mL/kg up to a maximum of 25 mL saline is instilled into the Foley catheter to establish a continuous fluid column with the pressure transducer, and IAP is recorded (10). IAP may be measured using a fluid column, in which case the reading is in cmH2O and should be converted to mm Hg by dividing by 1.36. Bladder detrusor muscle spasm may occur during saline instillation; thus, allowing time (30 seconds to 1 minute) for equilibration of pressures permits an accurate steady-state IAP to be measured (13). IAP should be expressed in mm Hg and measured at end-expiration in the supine position after ensuring that abdominal muscle contractions are absent and with the transducer zeroed at the level of the mid-axillary line.

performed via a urinary catheter. When the bladder is drained or has a minimal volume, the IAP is transmitted through the bladder’s compliant wall and is measured by transducing the urinary catheter. A minimum volume of 3 mL or 1 mL/kg up to a maximum of 25 mL saline is instilled into the Foley catheter to establish a continuous fluid column with the pressure transducer, and IAP is recorded (10). IAP may be measured using a fluid column, in which case the reading is in cmH2O and should be converted to mm Hg by dividing by 1.36. Bladder detrusor muscle spasm may occur during saline instillation; thus, allowing time (30 seconds to 1 minute) for equilibration of pressures permits an accurate steady-state IAP to be measured (13). IAP should be expressed in mm Hg and measured at end-expiration in the supine position after ensuring that abdominal muscle contractions are absent and with the transducer zeroed at the level of the mid-axillary line.

performed via a urinary catheter. When the bladder is drained or has a minimal volume, the IAP is transmitted through the bladder’s compliant wall and is measured by transducing the urinary catheter. A minimum volume of 3 mL or 1 mL/kg up to a maximum of 25 mL saline is instilled into the Foley catheter to establish a continuous fluid column with the pressure transducer, and IAP is recorded (10). IAP may be measured using a fluid column, in which case the reading is in cmH2O and should be converted to mm Hg by dividing by 1.36. Bladder detrusor muscle spasm may occur during saline instillation; thus, allowing time (30 seconds to 1 minute) for equilibration of pressures permits an accurate steady-state IAP to be measured (13). IAP should be expressed in mm Hg and measured at end-expiration in the supine position after ensuring that abdominal muscle contractions are absent and with the transducer zeroed at the level of the mid-axillary line.Intragastric, intrauterine, venacaval, and intrarectal sites have also been described for indirect measurement of IAP (14,15,16). The intravesical method is most often used in clinical practice because it is simple, reliable, and easily performed at the bedside. Kimball et al. using a standardized protocol for intravesical measurement demonstrated that intraobserver and interobserver variation in IAP readings is minimal (Pearson’s correlation coefficient 0.934 and 0.950, respectively) (17). Indirect intravesical IAP measurement can be performed using a commercially available kit or assembled low-cost components.

Direct Method

This method measures IAP directly from the peritoneal space using a pressure transducer or a fluid column. Direct measurement of IAP involves the placement of a needle or catheter into the peritoneum, making it more invasive, and generally less preferred than indirect measurement. However, if a preexisting catheter (such as a peritoneal dialysis catheter) is in place, the direct method can be used with equal ease (18).

The agreement between direct IAP measurement and indirect intravesical measurement has been studied in children. Two studies have shown that intravesical IAP measurement was most accurate with 1 mL/kg saline instilled into the bladder as

compared with larger volumes of instillation (18,19). Another study suggests that instilling a standard volume of 3 mL is as reliable as the 1 mL/kg volume for IAP measurements in children weighing less than 50 kg (10).

compared with larger volumes of instillation (18,19). Another study suggests that instilling a standard volume of 3 mL is as reliable as the 1 mL/kg volume for IAP measurements in children weighing less than 50 kg (10).

Variables Affecting IAP Readings

Many factors commonly encountered in critically ill patients may affect the accuracy of IAP measurements. In children, elevation of the head of the bed significantly increases the IAP. An elevation from 0° to 30° increased the IAP reading by 2 mm Hg (20). If the head of the bed cannot be lowered briefly for IAP measurement, subsequent IAP readings should also be measured at the same elevation for consistency of comparison. In this case, the IAP trend, rather than single readings, become more important. Unlike in adults, body mass index does not appear to affect IAP measurement (20,21). Inappropriately large instillation volume, transducer location, prone positioning, inadequate sedation, coughing, or agitation may all falsely raise measured IAP (13,21,22,23,24). High respiratory pressures and obesity have been shown to result in inaccurately high IAP in adults (23

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree