A GENERAL APPROACH TO ILL AND INJURED CHILDREN

MIRNA M. FARAH, MD, KHOON-YEN TAY, MD, AND JANE LAVELLE, MD

BACKGROUND

Children account for approximately 20% to 25% of all emergency department (ED) visits in the United States. In 2010, 25 million children <18 years of age were evaluated in EDs, comprising 20% of the 128 million total ED visits. The vast majority of children (96%) were treated and discharged from the ED. Younger children have the highest utilization rate; although infants <1 year old represent just 5% of the pediatric population, they comprised 12% of treat-and-release ED visits and almost 23% of inpatient admission. Children 1 to 4 years of age comprise 22% of this population, but account for 32.8% of all pediatric treat-and-release ED visits and 26.3% inpatient admissions. Approximately 5% of children will have severe illness. Over the past decades, as the application of new medical knowledge has eradicated many diseases and rendered others curable, trauma has emerged as the leading cause of morbidity and mortality. Children of all ages remain susceptible to infection. There are also more children with complicated health issues that depend on readily available sophisticated medical care. It is vital that emergency medicine clinicians can promptly recognize ill child and execute life-saving interventions.

PEDIATRIC DIFFERENCES

The medical evaluation of an infant or child can be challenging for all providers, but especially so for those who do not routinely care for children. Knowledge of development assists the clinician in determining the overall severity of illness. Fear or anxiety in acute situations is common and may be contributed to changes in mental status (MS) and vital signs (VSs). Preverbal infants and toddlers are less able to localize pain or discomfort. Children have remarkable resilience; initial signs of severe illness may be subtle; thus it is important to recognize warning signs of deterioration and intervene in a timely way. Clinicians must rely on parental and/or other caretaker accounts and perceptions of the history. Parental concerns must be considered carefully during care of the child. The approach to the care of the sick child, by nature must be family-centered. Ultimately, the task is the same for all emergency clinicians; rapid, accurate identification of serious, life-threatening illnesses, with swift intervention to reduce morbidity and mortality. This chapter outlines a standard approach to assist in achieving this goal.

RECOGNITION OF ILLNESS

Identifying the critically ill child is challenging. The defining principle of critical illness is the presence of an existing or potential threat to delivery of oxygen to meet the demands of the tissues. This is almost always the final common pathway that various childhood diseases lead to morbidity and mortality. The body’s oxygen delivery system is separated into the respiratory system (brings oxygen to the arterial blood) and the circulatory system (controls flow of oxygenated blood to the tissues). Critical illness leads to a global threat to oxygen delivery to all tissues of the body. The exceptions to this rule are diseases that compromise oxygen delivery to the central nervous system (CNS). By keeping the concept of life-threatening illnesses compromising oxygen delivery through respiratory, circulatory, or neurologic failure, clinicians can better evaluate and treat ill children. You will encounter this theme in the other chapters in this section, including the Chapter 2 Approach to the Injured Child, Chapter 3 Airway, Chapter 4 Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation, and Chapter 5 Shock.

Children with decreased or failured oxygen delivery to the skin, brain, kidneys, and cardiovascular system exhibit clinical findings in each of these organ systems. Manifestations of CNS hypoxia include irritability, confusion, delirium, seizures, and unresponsiveness. Cardiovascular manifestations include tachycardia, diaphoresis, bradycardia, and hypotension. Cutaneous manifestations include pallor, cyanosis, mottling, and poor capillary refill. In Chapter 4 Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation, Figure 4.2 shows the progression of physical examination findings associated with inadequate tissue oxygenation for each of these organ systems.

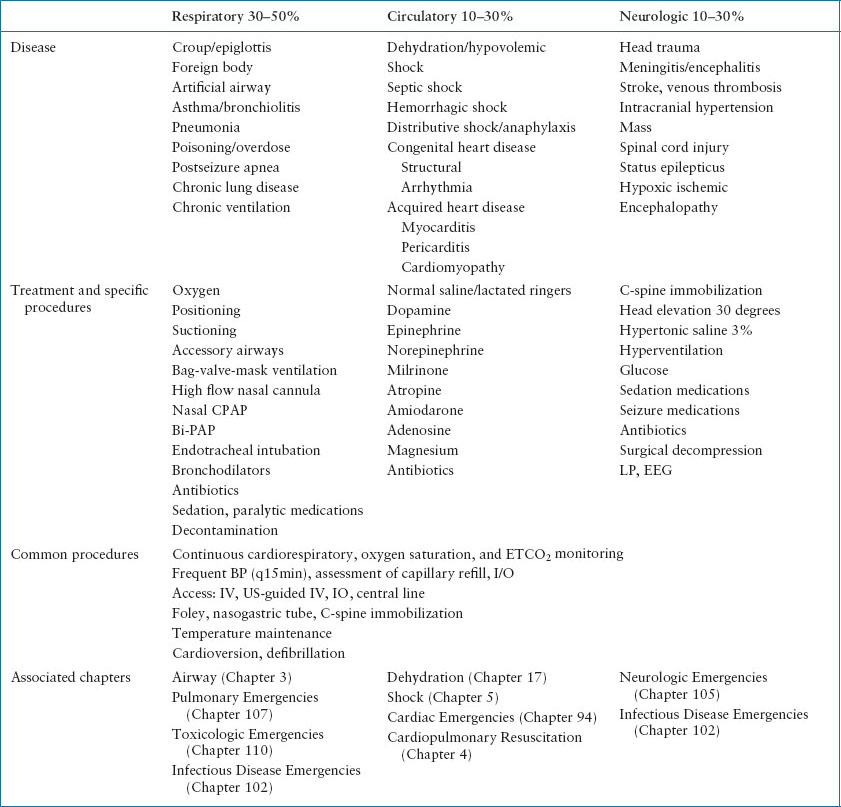

More than half of children with critical illness have disease affecting the respiratory system. Approximately 25% of children have diseases affecting the circulatory system presenting with hypovolemic, distributive, obstructive, or cardiogenic shock (see Chapter 5 Shock). CNS failure accounts for the final 25%. Table 1.1 lists examples of diseases that may cause severe illness in children, along with common medications and interventions needed to restore oxygen delivery and support vital function. Although there is overlap among organ system failures, in this table, the diseases are categorized by the primary organ system failure.

TABLE 1.1

RECOGNITION OF CRITICAL ILLNESS BY ORGAN SYSTEM

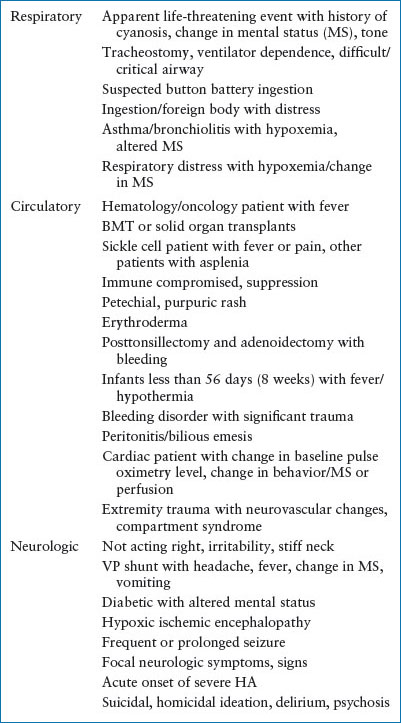

Triage

An organized triage system is a key component for early identification of children at risk for significant illness. The majority of pediatric EDs use the 5-level Emergency Severity Index (ESI) Triage system. Children are triaged to ESI 1, 2 by an experienced nurse by quick evaluation of MS, VSs, concerning chief complaints, and presence of high-risk conditions. Children triaged as ESI 1 require immediate evaluation, often by an organized rapid response team; those triaged as ESI 2 should ideally be assessed by clinicians within 30 minutes (see Chapter 73 Triage). Table 1.2 lists chief complaints, conditions, or characteristics of patients who may be at increased risk for respiratory, circulatory, or neurologic failure when they present to triage.

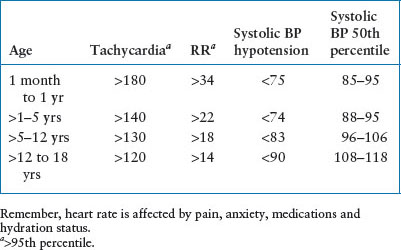

VITAL SIGNS

Measured VSs (heart rate [HR], respiratory rate, temperature, and pulse oximetry) significantly outside of the age-specific norms often signify potential for severe illness. Ready access to age-specific VS parameters is ideal as VS parameters vary significantly with age of the child. Temperature >38°C (100.4°F) in a neonate (<56 days) is considered a fever. VS reassessment is important to monitor evolving disease and response to interventions. VS abnormalities are sensitive warning signs of deterioration alerting the clinician team to intervene (Table 1.3).

TABLE 1.2

HIGH-RISK PATIENTS WITH INCREASED RISK FOR RESPIRATORY, CIRCULATORY, OR NEUROLOGIC FAILURE

SYSTEMS FOR A STANDARDIZED STRUCTURED RESPONSE

Patients triaged to ESI 1 (critical) are often best cared for in well-designed, fully stocked resuscitation room. These spaces allow immediate access to necessary equipment, medications, and ancillary services such as radiology. There is more room for staff to perform necessary interventions. It is optimal to care for children triaged as ESI 2 (emergent) in an ED examination room with monitors, oxygen and suction, and basic bedside equipment.

TABLE 1.3

HIGH-RISK VITAL SIGNS BY AGE

TEAM COMPOSITION

Ideally, children with critical illnesses are evaluated and treated by an organized, practiced team of providers. The physician team leader directs the overall assessment, interventions, and treatment. They receive input from the resuscitation team members, physiologic monitoring, and laboratory/radiographic data. Members of the resuscitation team include right and left bedside RN/Technician, a respiratory therapist, an RN documenter, and an RN or pharmacist to prepare medications. The roles of these providers should be explicitly defined in the ED Resuscitation Team Policy to assure an organized approach. Other physicians/CRNPs assist with physical examination, reassessments, and performance of necessary procedures. Child Life Specialists are helpful in distraction and calming techniques for fully conscious, not sedated patients. Social Workers or Charge RNs can accompany the family during the resuscitation and offer emotional support as well as an explanation of resuscitation events.

An automated communication alert to notify members of the resuscitation team allows for rapid response. A communication system to alert specialists, such as trauma, neurosurgery, critical care, anesthesiology, or otolaryngology physicians, should their assistance be needed emergently is also helpful. A clinical pharmacist is a valuable addition to the resuscitation team to assist with pediatric weight-based dosing. Special aids are available to provide pediatric weight-based doses and recommended equipment size based on the patient’s height/length or weight (see Figure 4.13, in Chapter 4 Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation). Skilled personnel (parent or provider) cannot accurately estimate a child’s weight on the basis of appearance. However, length is easily measured and tapes with precalculated medication doses and resuscitation equipment for various patient lengths have been clinically validated. Preparation of equipment ahead of time using precalculated weight-based doses of resuscitation medications and equipment sizes reduces error.

RAPID ASSESSMENT

A structured approach enables the team to assess the severity of illness and prioritize interventions. Although this rapid assessment is divided into the primary and secondary survey, it is a continuous and dynamic process with frequent reassessment. Tertiary diagnostic testing, subspecialty consultation, and timely transfer to the definitive care setting follow.

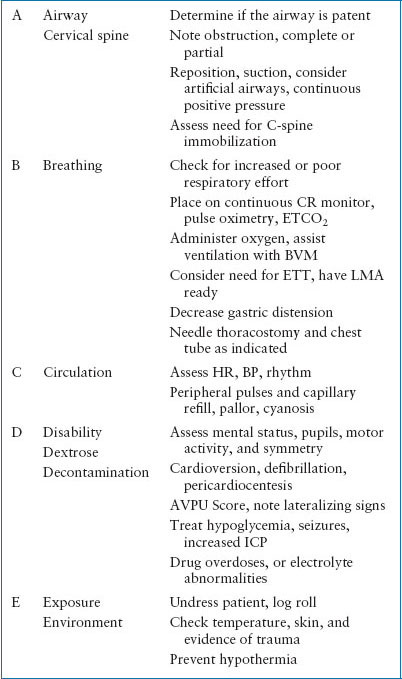

PRIMARY SURVEY

The goal of the primary survey is to identify and treat impending or existing respiratory, circulatory, and/or neurologic failure. This is initiated as soon as the patient arrives to the ED and is ideally completed in less than 5 minutes. Importantly, early recognition and treatment of a patient with deficiencies in ventilation, perfusion, or neurologic function frequently prevents deterioration to respiratory or cardiac arrest. It is important to monitor and reassess patients following interventions in order to quickly recognize deterioration. The physician performing the survey should be loud, clear, organized, and confident while verbalizing the ABCDE assessment of the patient; other team members perform life-saving procedures based on the findings of the surveyor (see Chapter 3 Airway, Chapter 4 Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation, Chapter 5 Shock, and Chapter 94 Cardiac Emergencies; Tables 1.4 and 1.5).

TABLE 1.4

PRIMARY SURVEY COMPONENTS

TABLE 1.5

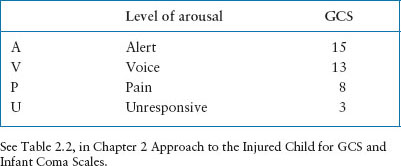

AVPU MNEMONIC FOR LEVEL OF CONSCIOUSNESS

Airway/Breathing

The respiratory system is divided into the extrathoracic airway (nostrils to trachea), the respiratory pump (muscles, pleura, respiratory control center), and the lung and intrathoracic airways. Respiratory failure due to extrathoracic obstruction presents with inspiratory stridorous or sonorous sounds along with decreased air entry and suprasternal retractions. Diseases that narrow the lumen of the intrathoracic airway cause expiratory wheezing. Diseases that increase airway resistance or decrease lung, or chest wall, compliance require greater effort on the child’s part to maintain alveolar ventilation. Children most often respond by reducing their tidal volume and increasing their respiratory rate. Even at the lower tidal volumes, negative pleural pressures must be greater than normal to suck open the intrathoracic airways or diseased lung to overcome the obstruction. Thus, intercostal and supraclavicular retractions are noted. Small infants depend more on diaphragmatic motion and may manifest seesaw motion. During inspiration the diaphragm descends/abdomen bulges and the chest collapses from lower pleural pressures. During expiration, the glottis closes, in infants and young children, grunting occurs when air escapes through an actively closed glottis in an attempt to maintain FRC. Respiratory center disease manifests as an irregular respiratory pattern with pauses or apnea. The most common cause of hypoxemia in children are hypoventilation and ventilation/perfusion mismatch. ETCO2 measurement may help to distinguish between them. With VQ mismatch the end tidal is normal or low in contrast to hypoventilation where the end tidal will be high. Diseases of the extrathoracic airway or the respiratory pump usually lead to hypoventilation with hypercarbia out of proportion to hypoxemia. Diseases of the lung and pump result in VQ mismatch with much greater hypoxemia than hypercarbia.

Treatment of extrathoracic airway includes airway positioning, suctioning, and NP/OP airways (Figure 4.4, in Chapter 4 Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation). Positive pressure and ETI may be required to overcome the obstruction. When disease primarily involves the lung and the intrathoracic airways, supplemental oxygen and positive end expiratory pressure are the main treatments. In addition, specific therapies such as bronchodilators, vasoconstrictors, anti-inflammatories or antibiotics target the underlying cause.

Circulation

The circulatory system includes the heart, the blood, the blood vessels, and the autonomic controls in the central and the peripheral nervous system. There is no single physical or laboratory finding that will identify shock, however, the physical signs exhibited by the patient in shock are ultimately due to insufficient oxygen and substrate delivery to the tissues. Recall that cardiac output (CO) is equal to mean arterial pressure divided by the systemic vascular resistance (MAP/SVR). Additionally, CO is also the product of the stroke volume (SV) and HR, (SV × HR), thus, MAP = HR × SV × SVR (see discussion in Chapter 5 Shock). HR and BP are easily measured, and the SVR can be assessed by physical examination of pulses, extremity temperature, color, and capillary refill. The physical manifestations vary with type of shock but include tachycardia, decreased skin perfusion, and hypotension; or tachycardia, bounding pulses and flushed skin with hypotension. If cardiogenic shock is present, HR may be normal or only modestly elevated. Remember that hypotension is a late finding requiring 50% decrease in the circulating volume. Treatment includes crystalloid infusion; increasing preload to increase SV. Contractility agents are considered if volume resuscitation 60 mL per kg is not effective. Afterload reduction may also be needed to treat cardiac dysfunction. It is important to correct hypoxemia acidosis and electrolyte abnormalities and provide other specific therapies to treat the underlying cause.

Disability

CNS failure is manifest by altered MS or focal neurologic deficit. Recall that the CNS is composed of the brain, the blood vessels, and the cerebrospinal fluid. Many diseases that cause CNS failure cause compartment physiology. Examples of primary CNS disease include intracranial hypertension/hemorrhage and status epilepticus. The CNS may also be secondarily affected by respiratory or circulatory disease. The AVPU scale (Table 1.5) and GCS (Table 2.2, in Chapter 2 Approach to the Injured Child) are used to measure level of consciousness in a standardized way. Interventions to treat CNS failure include modest hyperventilation, maintenance of MAP and oxygenation, hypertonic therapy, avoidance of hyperthermia, and potentially induce hypothermia. Other therapies aimed at the underlying cause include anticonvulsants, antibiotics, and surgical decompression.

Exposure/Environment

A complete physical examination requires removal of all clothing, log rolling, and checking axillary areas of the patient. Monitor and maintain body temperature using increased ambient temperature, warm blankets, and warmed fluids and oxygen. The use of therapeutic hypothermia in arrested pediatric patients remains controversial, however, hyperthermia should be treated aggressively. Lowering of core body temperature to 32 to 34 degrees during the first few hours after cardiac arrest is associated with improved neurologic outcomes and decreased mortality in adults with an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. In children, evidence is very limited. The use of therapeutic hypothermia may be considered for children with out-of-hospital arrest and persistent coma or those with ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia.

IV Access

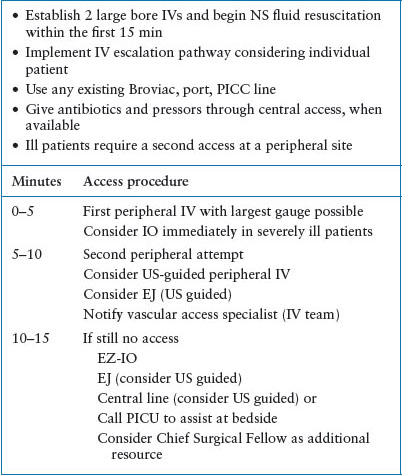

Vascular access in peripheral veins of the upper extremity with a large bore short catheter is preferred. For patients in pulseless arrest, with severe hypotension, or difficult access in which immediate access is ideal, intraossesous access provides a quick, reliable route to provide fluid resuscitation and medications. The ED clinicians should have an IV escalation plan in place with resources to assure timely IV access. This has become more important aspect of care due to the increasing numbers of children with difficult IV access due to success in treating chronic illnesses (Table 1.6).

TABLE 1.6

IV ESCALATION PLAN

Fluid Resuscitation

Deliver isotonic fluids (normal saline or lactated ringers) rapidly in 20 mL per kg aliquots up to 1,000 mL and reassess VS, MS, and skin perfusion. The push–pull technique using a 30-mL syringe with a macrodrip setup with a three-way stopcock and a T-connector is useful for rapid fluid resuscitation in children <50 kg. For children >50 kg, fluids can be infused using a pressure bag or a rapid infuser. To date, evidence has not shown benefit for the use of albumin or synthetic colloids in pediatric septic shock, cardiopulmonary arrest, or trauma. Dextrose-containing solutions should not be used for initial resuscitation due to risk for hyperglycemia and secondary osmotic diuresis and neurologic injury. Bedside glucose testing is important, treat hypoglycemia with D10 or D25 and follow with an infusion of fluids including dextrose. Other critical electrolyte abnormalities should be treated.

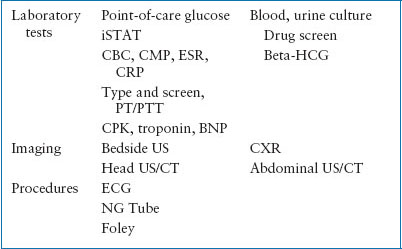

The choice of laboratory and imaging studies is guided by the patient’s differential diagnosis (Table 1.7). Medications commonly used in pediatric resuscitation are listed in Table 4.6 of Chapter 4 Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation.

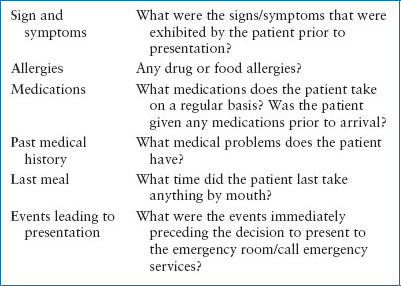

When time is limited in obtaining a pediatric history, providers can remember the acronym “SAMPLE,” to briefly obtain key elements (Table 1.8). Other important information may include medications available in the home, travel history, immunizations, social history and stressors, suicide risk, substance abuse, and sexual assault.

TABLE 1.7

PRIMARY SURVEY: DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES AND PROCEDURES

SECONDARY SURVEY

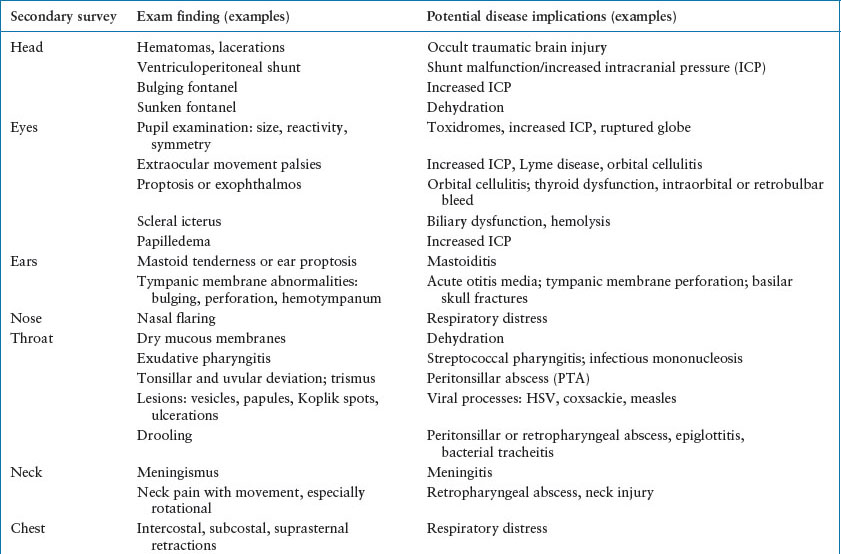

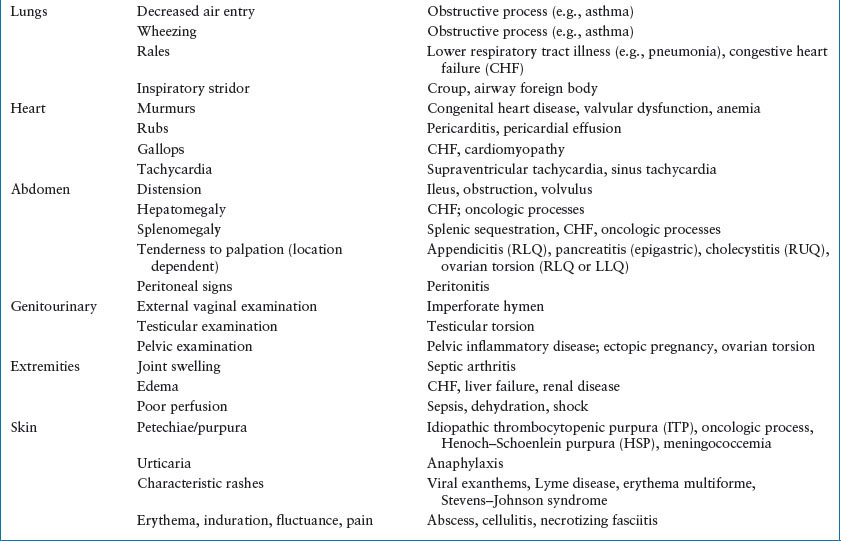

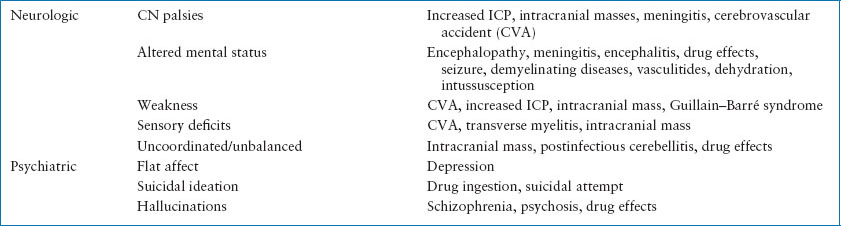

The goal of the secondary survey is to identify the definitive cause of the respiratory, circulatory, and/or neurologic abnormalities treated during the primary survey.

A systematic head-to-toe examination is performed with special attention to specific organ systems associated with the patient’s chief complaint. Elements of the secondary survey may be skipped or deferred, depending on the clinical situation, patient acuity, and patient stability (Table 1.9).

FAMILY PRESENCE

Family presence (FP) during resuscitation and procedures has become an increasingly common practice; and is endorsed by the AAP, ACEP, and ENA. Family members who were at the side of a loved one during the final moments of life believe that their presence was beneficial to the patient and to themselves, and was helpful in their adjustment and grieving process. FP also promotes good communication with the clinician team. It allows parents to comfort and support their child, allowing children to be more cooperative so the evaluation and treatments go more smoothly. Studies have also shown that in the overwhelming majority, FP is not disruptive, and does not create stress among staff or negatively affect their performance. In general, the more experience healthcare providers have with FP and dealing with distressed families, the higher their acceptance and success of FP. Parents often fail to ask, but healthcare providers are obligated to offer the opportunity whenever possible. Written institution-specific guidelines, and resources including dedicated family support person (FSP) during resuscitation, are among the crucial initial steps toward a successful FP experience. The FSP assesses and prepares family members prior to treatment and remains with the family to provide comfort and answer questions. The family is initially escorted to a designated area within the treatment room away from the bedside; they can then be brought to the head of the bed at the completion of the secondary survey and all urgent procedures. The designated FSP can be a social worker, nurse, or chaplain who has no direct patient care responsibility, has a good knowledge of grief reactions, and is assigned exclusively to assist the family. If family members become overwhelmed or interfere with patient care, the FSP should respectfully escort them out of the treatment room. Families can also choose to leave the room at any time, and may stay or leave during invasive procedures or resuscitations. Patients who choose not to have family members present, or family members who desire not to participate must be supported in their decision without judgment. The AAP recommends that all EDs have a policy and procedure in place to support this.

TABLE 1.8

SAMPLE HISTORY

QUALITY AND COMPETENCY

The vast majority (>80%) of children are seen in community (nonpediatric) EDs; 50% of US EDs see fewer than 10 children per day. Critically ill children may only be encountered a few times per year. The Emergency Medical Services for Children (EMSC), a federal program designed to ensure that all children have access/receive appropriate care in an emergency, completed a national assessment with the Pediatric Readiness Survey in March 2013. Over 80% of EDs responded to the survey. EDs with low-volume pediatric visits (<1,800 per year) were the least pediatric ready (average score of 62/100), and EDs with higher-volume pediatric visit (>10,000 per year) were the most pediatric ready (average score of 84/100). The average score across over 4,000 hospitals was 69.

There are several strategies that can be implemented in general EDs in order to increase readiness for child patients and help to standardize key components of pediatric care for common medical diseases. Evidence- and concensus-based guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics as well as individual institutional pathways facilitate translation of evidence into bedside care. Some examples include AAP guidelines for bronchiolitis, acute otitis media and febrile UTI, IDSA guidelines for skin and soft tissue infection and community-acquired pneumonia, and NHBLI guidelines for asthma. Additionally, several pediatric institutions developed pathways; Seattle Children’s Hospital and The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia have made these available to all clinicians on the Internet.

It is also important to provide opportunities for the ED clinicians to maintain resuscitation skills. Workshops with simulation for hands-on practice of key resuscitation skills should be offered throughout the year. It is also valuable for the ED team members to practice using resuscitation simulation scenarios in their own resuscitation room, ideally with members of the multidisciplinary team. In addition to cognitive and skill practice, these simulation sessions provide a venue to improve team collaboration and communication. Clinicians may also benefit from maintaining PALS, ACLS, and ATLS certification.

TABLE 1.9

SECONDARY SURVEY: FINDINGS AND IMPLICATIONS

Quality improvement initiatives for pediatric resuscitations can take multiple forms. Videotaped resuscitations can be reviewed by a multidisciplinary team to identify areas for system improvements, opportunities for targeted clinician education, and improved teamwork and communication. Resuscitation cases can be reviewed in advanced case conferences for in-depth discussion around medical including the most recent evidence. Data can be extracted from the EMR for process and outcome quality measures to further improve/inform care.

SUMMARY

The critically ill child manifests signs related to potential or existing threat to the delivery of oxygen to meet the demands of tissues. This is the final common pathway that leads to morbidity and mortality in the majority of childhood diseases.

KEY POINTS

Clinicians should rapidly assess the ABCDE (airway, breathing, circulation, disability, exposure) components of the primary survey while performing life-saving procedures

Clinicians should rapidly assess the ABCDE (airway, breathing, circulation, disability, exposure) components of the primary survey while performing life-saving procedures

An efficient, targeted history and secondary survey can offer clues to the assessment and diagnosis of an acutely ill child.

An efficient, targeted history and secondary survey can offer clues to the assessment and diagnosis of an acutely ill child.

Healthcare providers should offer the family the opportunity to be present during resuscitations and procedures whenever a family support person is available.

Healthcare providers should offer the family the opportunity to be present during resuscitations and procedures whenever a family support person is available.

Institutions should invest time and resources into periodic multidisciplinary training sessions for their providers to refresh and practice pediatric resuscitation skills in their own environment with their own equipment and resources.

Institutions should invest time and resources into periodic multidisciplinary training sessions for their providers to refresh and practice pediatric resuscitation skills in their own environment with their own equipment and resources.

Many modalities exist for monitoring the quality and competency of pediatric care delivered to acutely ill children and can serve to improve that care on an ongoing basis.

Many modalities exist for monitoring the quality and competency of pediatric care delivered to acutely ill children and can serve to improve that care on an ongoing basis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree