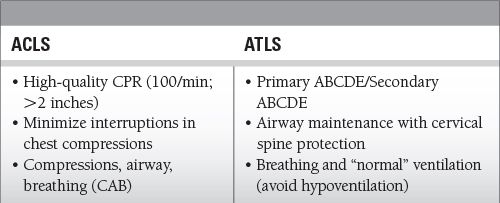

High-quality CPR with adequate rate (100/min) and depth (2 inches)

Minimize interruptions in chest compressions

Minimize interruptions in chest compressions

Avoid excessive ventilation

Avoid excessive ventilation

Treat most significant injury first

Treat most significant injury first

Expose patient, but prevent hypothermia

Expose patient, but prevent hypothermia

Early and successful treatment during ACLS/ATLS protocols starts with effective leadership by code team leader

Early and successful treatment during ACLS/ATLS protocols starts with effective leadership by code team leader

Common Themes to Remember

Epidemiology

Leading cause of death overall is diseases of the heart—598,607 people annually

Leading cause of death overall is diseases of the heart—598,607 people annually

Leading cause of death from ages 1 to 44 years is accidents (unintentional injuries)—117,176 people annually

Leading cause of death from ages 1 to 44 years is accidents (unintentional injuries)—117,176 people annually

Trauma is the leading cause of mortality globally

Trauma is the leading cause of mortality globally

Key Pathophysiology

ACLS: 5 Hs and 5 Ts (discussed in detail below)

ACLS: 5 Hs and 5 Ts (discussed in detail below)

ATLS: identify life-threatening injuries and treat

ATLS: identify life-threatening injuries and treat

2010 ACLS Guidelines

Key changes from the 2005 ACLS Guidelines

Key changes from the 2005 ACLS Guidelines

Capnography for confirming and monitoring ETT placement

Capnography for confirming and monitoring ETT placement

Importance of high-quality CPR (adequate rate 100/min and depth > 2 inches)

Importance of high-quality CPR (adequate rate 100/min and depth > 2 inches)

Atropine is no longer recommended for use in pulseless electrical activity (PEA) or asystole.

Atropine is no longer recommended for use in pulseless electrical activity (PEA) or asystole.

Chronotropic drug infusions as an alternative to pacing in symptomatic and unstable bradycardia.

Chronotropic drug infusions as an alternative to pacing in symptomatic and unstable bradycardia.

Adenosine is recommended as a safe and potentially effective therapy in the initial management of stable undifferentiated regular monomorphic wide-complex tachycardia.

Adenosine is recommended as a safe and potentially effective therapy in the initial management of stable undifferentiated regular monomorphic wide-complex tachycardia.

Consider activating emergency response system

Consider activating emergency response system

Airway and ventilation

Airway and ventilation

Every second without CPR means a lack of cardiac and cerebral perfusion

Every second without CPR means a lack of cardiac and cerebral perfusion

The mainstay of ACLS starts with effective CPR consisting of adequate depth (≥2 inches [5 cm]) and rate (100/min) of compressions allowing complete recoil; rotate compressor every 2 minutes.

The mainstay of ACLS starts with effective CPR consisting of adequate depth (≥2 inches [5 cm]) and rate (100/min) of compressions allowing complete recoil; rotate compressor every 2 minutes.

Advanced airway placement in cardiac arrest should not delay initial CPR and defibrillation for ventricular fibrillation (VF) cardiac arrest.

Advanced airway placement in cardiac arrest should not delay initial CPR and defibrillation for ventricular fibrillation (VF) cardiac arrest.

Securing the airway should be done by experienced providers, using their “best” method first—ideally done in <10 seconds.

Securing the airway should be done by experienced providers, using their “best” method first—ideally done in <10 seconds.

Indications for emergency endotracheal intubation are inability to ventilate with bag and mask and the absence of airway protective reflexes.

Indications for emergency endotracheal intubation are inability to ventilate with bag and mask and the absence of airway protective reflexes.

Use of 100% inspired oxygen during CPR optimizes arterial oxyhemoglobin content and thus oxygen delivery.

Use of 100% inspired oxygen during CPR optimizes arterial oxyhemoglobin content and thus oxygen delivery.

Continuous waveform capnography is recommended in addition to clinical assessment as the most reliable method of confirming and monitoring correct placement of an ETT.

Continuous waveform capnography is recommended in addition to clinical assessment as the most reliable method of confirming and monitoring correct placement of an ETT.

Breath sounds should not be heard over the epigastrium.

Breath sounds should not be heard over the epigastrium.

Compression: ventilation ratio of 30:2 (if no advanced airway)

Compression: ventilation ratio of 30:2 (if no advanced airway)

Deliver 1 breath every 6 to 8 seconds (if advanced airway is present)

Deliver 1 breath every 6 to 8 seconds (if advanced airway is present)

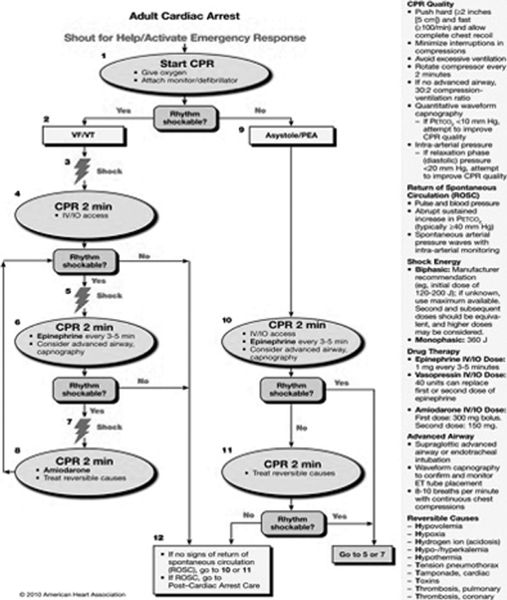

Management of cardiac arrest

Management of cardiac arrest

Shout for help/activate emergency response

Shout for help/activate emergency response

Start CPR

Start CPR

Cardiac arrest rhythms: VF, pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT), PEA, and asystole

Cardiac arrest rhythms: VF, pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT), PEA, and asystole

Both BLS and ACLS with integrated postcardiac arrest care

Both BLS and ACLS with integrated postcardiac arrest care

High-quality CPR for all cardiac arrest rhythms is of fundamental importance —>2 inches for depth and >100/min for rate

High-quality CPR for all cardiac arrest rhythms is of fundamental importance —>2 inches for depth and >100/min for rate

Only rhythm-specific therapy proven to increase survival to hospital discharge is defibrillation of VF/pulseless VT

Only rhythm-specific therapy proven to increase survival to hospital discharge is defibrillation of VF/pulseless VT

Diagnose and treat the 5 Hs and 5 Ts

Diagnose and treat the 5 Hs and 5 Ts

5 Hs

5 Hs

Hypoxia

Hypoxia

Hypovolemia

Hypovolemia

Hydrogen ion (acidosis)

Hydrogen ion (acidosis)

Hypokalemia/Hyperkalemia

Hypokalemia/Hyperkalemia

Hypothermia

Hypothermia

5 Ts

5 Ts

Toxins

Toxins

Tamponade (cardiac)

Tamponade (cardiac)

Tension pneumothorax

Tension pneumothorax

Thrombosis, pulmonary

Thrombosis, pulmonary

Thrombosis, coronary

Thrombosis, coronary

VF (disorganized electrical activity) or pulseless VT (organized electric activity of the ventricular myocardium)

VF (disorganized electrical activity) or pulseless VT (organized electric activity of the ventricular myocardium)

If rhythm check by an automated external defibrillator, manual defibrillator, or a provider identifies VF or pulseless VT a single shock should be delivered.

If rhythm check by an automated external defibrillator, manual defibrillator, or a provider identifies VF or pulseless VT a single shock should be delivered.

Biphasic defibrillation: use initial energy dose of 120 to 200 J

Biphasic defibrillation: use initial energy dose of 120 to 200 J

Monophasic defibrillation: use initial energy dose of 360 J

Monophasic defibrillation: use initial energy dose of 360 J

After initial shock, resume CPR immediately for 2 minutes before the next rhythm check.

After initial shock, resume CPR immediately for 2 minutes before the next rhythm check.

If VF or pulseless VT persists after at least one shock and a cycle of CPR, epinephrine 1 mg or vasopressin 40 units may be given.

If VF or pulseless VT persists after at least one shock and a cycle of CPR, epinephrine 1 mg or vasopressin 40 units may be given.

Amiodarone 300 mg bolus for first dose and 150 mg for second dose may be given if VF/VT is refractory to above treatments.

Amiodarone 300 mg bolus for first dose and 150 mg for second dose may be given if VF/VT is refractory to above treatments.

If amiodarone is unavailable, lidocaine may be considered.

If amiodarone is unavailable, lidocaine may be considered.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree