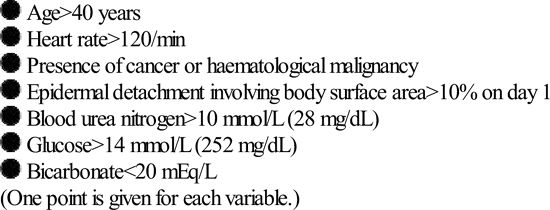

Edited by Anthony Brown Rebecca Dunn, George Varigos and Vanessa Morgan The pattern and form of acute dermatological conditions that present to the emergency department (ED) are confusing in that the clinical features, such as vasodilatation, exfoliation, blistering or necrosis, are the common endpoint of many different inflammatory processes in the skin. The pathological process involves cytokines or chemokines and their effects create the visible response(s). The important clinical differences seen in these acute reactions should be recognized by the trained observer (Tables 15.1.1 and 15.1.2). This chapter aims to provide a clinical pathway from taking an appropriate history to having knowledge of the distinguishing clinical features of the likely differential diagnoses. The emergency presentations discussed are limited to specific dermatological conditions that may be seen in an ED as a true urgency. Table 15.1.1 Definition of macroscopic skin pathological lesions With permission from Rook AJ, Burton JL, Champion RH, Ebling FJG. Diagnosis of skin disease. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R (eds). Textbook of Dermatology. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific; 1992. Table 15.1.2 Definitions of patterns in skin disorders It is important to use other resources with this chapter, such as a dermatology atlas or specialized texts, to provide greater detail on the conditions mentioned. The presentation of skin and soft-tissue infections (Chapter 9.5) and anaphylaxis (Chapter 2.8) are covered elsewhere. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) and Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) are acute severe reactions characterized by extensive necrosis and detachment of the epidermis defined by mucosal ulceration at two or more sites usually with cutaneous blisters. Confusion exists between these two diagnoses and erythema multiforme (EM). EM was previously considered a variant of SJS/TEN, but it is now commonly accepted that they are clinically distinct disorders with different causes and prognosis. Most consider EM minor and major to be related to infections and SJS/TEN as variants (mild and severe) or a separate disorder, usually due to drugs. However, this distinction is not important in the emergency setting, but rather it is the recognition of a potentially serious dermatosis that is important. The difference between TEN and SJS is defined by the extent of skin involvement. TEN affects more than 30% of the body surface area, whereas SJS affects 10% or less (Fig. 15.1.1). ‘TEN/SJS overlap’ refers to patients where there is between 10 and 30% body surface area involvement. The extent of necrolysis must be carefully evaluated since it is a major prognostic factor. Patients with HIV, collagen vascular disease and malignancy are at increased risk of TEN. Clinical features of SJS/TEN include a prodrome with upper respiratory tract- (URTI) like symptoms, fever, malaise, vomiting and diarrhoea. Skin pain may herald the development of SJS/TEN and should not be dismissed. Symmetrical erythematous macules, mainly localized on the trunk and proximal limbs, evolve progressively to dusky erythema and confluent flaccid blisters leading to epidermal detachment. The key to making the diagnosis is recognizing mucosal involvement, which may include conjunctival, oral mucosal, genital and sometimes perianal erosions, as well as an often severe haemorrhagic cheilitis. Gastrointestinal and respiratory mucosa can also be involved. Nikolsky sign is positive, that is dislodgement of the epidermis by lateral finger pressure in the vicinity of a lesion causes an erosion, or pressure on a bulla leads to lateral extension of the blister. TEN is almost always due to drug ingestion which may, in rare instances, include illicit drug ingestion. Therefore, ask about prescribed and over-the-counter drugs, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), sulphonamides, allopurinol, nevirapine and anticonvulsants, such as sodium valproate and lamotrigine, as well as illicit drug use. Request a full blood count (FBC), urea and electrolytes (U&E), liver function tests (LFT) and a blood glucose. These may also be used to calculate the prognostic SCORTEN (see below). Other tests to consider include antinuclear antibody (ANA), extractable nuclear antigens (ENA), double stranded DNA (dsDNA), C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), anti-skin antibodies, HIV and mycoplasma serology. Skin swabs for viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and bacterial culture should be taken and chest X-ray (CXR), urine and blood cultures as indicated. Biopsies are taken from the edge of a blister for histology and a perilesional site for immunofluorescence. Clearly state on the request slip that the differential diagnosis is of toxic epidermal necrolysis. Epidermal (keratinocyte) necrosis is the histological hallmark of this condition. Cease the triggering drug or agent immediately and involve the intensive care unit and/or the burns unit. Rapid institution of resuscitation measures is associated with a more favourable prognosis. Arrange assessment and treatment by the ophthalmology and ear, nose and throat teams for ocular and oral/pharyngeal involvement, respectively. TEN may continue to evolve and extend over days, unlike a burn, where the initial insult occurs at a defined time. The SCORTEN severity scoring system for TEN (Table 15.1.3) is similar in concept to the Ranson’s score for pancreatitis. Calculate the SCORTEN severity score within 24 h of admission and again on day 3 to aid the prediction of possible death (Table 15.1.4). Table 15.1.3 SCORTEN severity score for toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) Table 15.1.4 *Guegan S, Bastuji-Garin S, PoszepczynskaGuigne E, et al. Performance of the SCORTEN during the first five days of hospitalization to predict the prognosis of epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol 2006;126:272–6. While not life threatening, EM is part of the differential of a potentially life-threatening reaction, such as SJS/TEN. EM is an acute usually mild, self-limited cutaneous and/or mucocutaneous syndrome that presents with the rapid onset of lesions within a few days, favouring acral sites. These are often mildly pruritic or painful papular or urticarial lesions, as well as the classical ‘target’ lesions, but with only one mucous membrane involved (EM major) or none (EM minor). Typically, the oral mucosa is involved showing a few, discrete, mildly symptomatic erosions. Rarely, the eye, nasal, urethral or anal mucosa may be involved. A mild prodrome may precede development of the rash. Most cases of EM are due to infection, most commonly Herpes simplex virus (HSV) or Mycoplasma. Drugs are now considered to be an uncommon cause (Fig. 15.1.2). Send a baseline FBC, U&E, LFT and CRP, as well as a skin biopsy if the diagnosis is uncertain, swabs and/or serology for HSV. Request a CXR and mycoplasma serology if there are respiratory symptoms. Usually, only symptomatic treatment is required with topical steroids, antihistamines, antiseptic mouthwashes and local anaesthetic preparations for oral involvement. For severe cases, treat erythema multiforme with a systemic steroid, such as predinosolone (0.5–1 mg/kg/day). In recurrent EM due to HSV, oral antivirals are effective. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) may resemble severe EM in the acute oedematous phase, presenting with fever, arthralgia, neutrophilia and sterile, non-infective but painful pustules, plaques or nodules over the head, trunk and arms. It may recur and can be associated with inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis or other connective tissue diseases, haematological malignancy, such as myeloid leukaemia, pregnancy or infection, such as streptococcal or Yersinia (Fig. 15.1.3). Sweet’s syndrome is highly responsive to systemic steroids, however, any underlying association must be sought and excluded by appropriate investigations. DRESS is a severe skin reaction with systemic manifestations that carries significant morbidity and a mortality rate of 10%. It usually occurs during the first prolonged course of a responsible associated drug, typically within 2–6 weeks of starting. It has been reported with the aromatic antiepileptics (phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbital), lamotrigine, sulphonamides (including sulphamethoxazole and trimethoprim combinations and dapsone), minocycline, allopurinol, terbinafine, abacavir and nevirapine. Up to 70% cross-reactivity occurs between different aromatic anticonvulsants which should therefore be avoided if someone has previously had a major reaction to an aromatic antiepileptic. Fever and rash are the most common symptoms. Cutaneous involvement is often polymorphic usually starting as a maculopapular rash which may later become oedematous, exfoliative or erythrodermic and/or include non-follicular pustules. Often, rash involving the face indicates a more serious drug reaction and facial oedema and lymphadenopathy are frequent hallmarks of this syndrome. Prominent eosinophilia is a characteristic feature that occurs in 60–70% of cases. Potentially serious internal organ involvement, such as hepatitis, nephritis, pneumonitis, myocarditis, thyroiditis, encephalitis and haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) syndrome, can occur. Fever, skin rash and organ involvement may fluctuate and persist for weeks or months after drug withdrawal, with the delayed onset of sequelae reported. Diagnosis can be difficult because of the polymorphic rash and variable organ involvement. A skin biopsy should be taken for histopathology and, although not diagnositic, histological features of a drug reaction will assist in making the diagnosis. Also request a basline FBC, U&E and LFT. Immunoglobulins and viral serology (Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), human herpesvirus 6 or 7 (HHV6, HHV7) should be sent, as transient hypogammaglobulinaemia and viral reactivation may be associated with fluctuations in symptoms. Other investigations should be as directed for systemic involvement. This usually includes admission to hospital and ceasing the suspected drug. Corticosteroids are first line of therapy despite no consensus on dose or regimen. Fluctuation in symptoms and relapse can occur when the dosage is tapered. As a result, steroid therapy sometimes has to be maintained for several weeks, even months and a steroid-sparing agent may be required. Antivirals and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) are emerging as potentially useful therapies for this condition. In milder cases, topical high-potency corticosteroids may be helpful for skin manifestations. The causes of erythroderma include eczema (40%), psoriasis (22%), drugs (15%), lymphoma (Sezary syndrome) (10%) and idiopathic (8%). Seek a history of previous skin disease, recent medications or recent changes to skin management, assess hydration and cardiac status, check for oedema, respiratory infection and a deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Send an FBC with film and differential, U&E, LFTs and blood cultures if the temperature is greater than 38°C, or if the patient appears unwell with rigors, even if the temperature is normal, as the patient may have become poikilothermic but is still septic. Send skin swabs for microscopy and culture and request a chest X-ray. Arrange biopsy of the skin if the cause of the erythroderma is uncertain. Arrange to admit the patient. Treatment is general and supportive and includes:

Dermatology Emergencies

15.1 Emergency dermatology

Introduction

Papule

Circumscribed firm raised elevation, less than 0.5 cm in diameter

Nodule

A solid or firm mass more than 0.5 cm in the skin which can be observed as an elevation or can be palpated

Purpura

Discoloration of skin or mucous membranes due to extravasation of red blood cells

Pustule

A visible accumulation of fluid, usually yellow, in the form of a vesicle or papule containing the fluid

It may be centred around a pore, such as a hair follicle or sweat glands, and sometimes appears in normal skin, not uncommonly palmar/plantar

Vesicle

A visible accumulation of fluid in a papule of<5 mm

The fluid is clear, serous-like and is located within or beneath the epidermis

Blister or bulla

Large fluid-containing lesion of more than 5 mm

Plaque

An area or sheet of skin elevated and with a distinct edge, of any shape and usually wider than 1 cm

Annular

Ring-like or part of a circle

Linear

Line-like

Arcuate

Arch-like

Grouped

Local collection of similar lesions

Unilateral

One side

Symmetrical

Both sides

Potentially life-threatening dermatoses

Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens–Johnson syndrome

Clinical features

Investigations

Management

Score

Mortality (%)

0–1

3.2

2

12.1

3

35.3

4

58.3

5 or greater

90.0

Erythema multiforme

Investigations

Management

Sweet’s syndrome

Drug rash with eosinophilia (DRESS)

Investigations

Management

Erythroderma

Complications of erythroderma

Investigations

Management

attention to temperature control, avoiding hypothermia

attention to temperature control, avoiding hypothermia

referral to dietitian for high protein diet in the first 24 h

referral to dietitian for high protein diet in the first 24 h

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

15. Dermatology Emergencies

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue