Edited by Mark Little Lindsay Murray Anaemia is a condition in which the absolute number of red cells in the circulation is abnormally low. The diagnosis is usually made on the basis of the full blood count (FBC). This, together with the blood film, offers qualitative as well as quantitative data on the blood components and a set of normal values is shown in Table 13.1.1. Table 13.1.1 Full blood count: normal parameters The average lifespan of a normal red blood cell in the circulation is from 100 to 120 days. Aged red cells are removed by the reticuloendothelial system but, under normal conditions, are replaced by the marrow such that a dynamic equilibrium is maintained. Anaemia develops when red cell loss exceeds red cell production. It follows that the anaemic patient is doing at least one of three things: not producing enough red cells, destroying them too quickly or bleeding. The overriding functional importance of the red cell resides in its ability to transport oxygen, bound to the haemoglobin molecule, from the lungs to the tissues. Functionally, anaemia may be regarded as an impairment in the supply of oxygen to the tissues and the adverse effects of anaemia, from whatever cause, are a consequence of the resultant tissue hypoxia. Anaemia is not a diagnosis: rather, it is a clinical or a laboratory finding that should prompt the search for an underlying cause (Table 13.1.2). Table 13.1.2 Haemorrhage Traumatic Non-traumatic Acute Chronic Megaloblastic anaemia Vitamin B12 deficiency Folate deficiency Aplastic anaemia Pure red cell aplasia Myelodysplastic syndromes Invasive marrow diseases Chronic renal failure Decreased RBC survival (haemolytic anaemia) Congenital Spherocytosis Elliptocytosis Glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase deficiency Pyruvate kinase deficiency Haemoglobinopathies: sickle cell diseases Acquired autoimmune haemolytic anaemia, warm Acquired autoimmune haemolytic anaemia, cold Microangiopathic haemolytic anaemias RBC mechanical trauma Infections Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria By far the most common cause of severe anaemia encountered in the emergency department (ED) is haemorrhage. Therefore, the assessment of the anaemic patient is often chiefly concerned with the search for a site of blood loss. The most common causes of haemorrhage are outlined in Table 13.1.3. However, the emergency physician must remain alert to the possibility that the patient is not bleeding but manifesting a rarer pathological condition. Table 13.1.3 Common causes of haemorrhage in the emergency department Trauma Blunt trauma to mediastinum Pulmonary contusions/haemopneumothorax Intraperitoneal injury Retroperitoneal injury Pelvic disruption Long bone injury Open wounds: inadequate first aid Non-trauma Gastrointestinal haemorrhage Oesophageal varices Peptic ulcer Gastritis/Mallory–Weiss Colonic/rectal bleeding Obstetric/gynaecological bleeding Ruptured ectopic pregnancy Menorrhagia Threatened miscarriage Antepartum haemorrhage Postpartum haemorrhage Other Epistaxis Postoperative Secondary to bleeding diathesis While it may be obvious on history and examination that a patient is bleeding, occasionally, the source of blood loss is occult and the extent of loss underestimated. In the context of trauma, the history often gives clear pointers to both sites and extent of blood loss. Consideration of the mechanism of injury may allow anticipation of occult pelvic, intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal bleeding. Intracranial bleeding is never an explanation for hypovolaemic shock in an adult. In the context of non-trauma, it is essential to obtain an obstetric and gynaecological history in women of childbearing age. The remainder of the formal history may supply information essential in determining the aetiology of anaemia. The past medical history may point to a known haematological abnormality or to a chronic disease process. A drug and allergy history is always relevant. Many drugs cause marrow suppression, haemolytic anaemia and bleeding. The family history points to hereditary disease; the social history may alert the clinician to an unusual occupational exposure in the patient’s past or, more likely, to recreational activities liable to exacerbate an ongoing disease process. The systems review is particularly relevant to the consultation with middle-aged or elderly male patients, who must be asked about symptoms of altered bowel habit and weight loss. The symptomatology of anaemia proceeds from vague complaints of tiredness, lethargy and impaired performance through to more sharply defined entities, such as shortness of breath on exertion, giddiness, restlessness, apprehension, confusion and collapse. Co-morbid conditions may be exacerbated (the dyspnoea of chronic obstructive airway disease) and occult pathologies unmasked (exertional angina in ischaemic heart disease). Anaemia of insidious onset is generally better tolerated than that of rapid onset because of cardiovascular and other compensatory mechanisms. Acute loss of 40% of the blood volume may result in collapse whereas, in certain developing countries, it is not rare for patients with haemoglobin concentrations 10% of normal to be ambulant. Trauma superimposed on an already established anaemia can lead to rapid decompensation. The cardinal sign of anaemia is pallor. This can be seen in the skin, the lips, the mucous membranes and the conjunctival reflections. Yet, not all anaemic patients are pallid and not all patients with a pale complexion are anaemic. Patients who have suffered an acute haemorrhage may show evidence of hypovolaemia: tachycardia, hypotension, cold peripheries and sluggish capillary refill. The detection of postural hypotension is an important pointer towards occult blood loss. Conversely, patients with anaemia of insidious onset are not hypovolaemic and may manifest high-output cardiac failure as a physiological response to hypoxia. Other features of the physical examination may provide clues to the aetiology of anaemia. The glossitis, angular stomatitis, koilonychia and oesophageal web of iron- deficiency anaemia are uncommon findings. Bone tenderness, lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly and splenomegaly may point to an underlying haematological abnormality. The rectal and gynaecological examinations can sometimes be diagnostic. The full blood count often reveals an anaemia that has not been clinically suspected and that must be interpreted in the light of the history and examination. If the anaemia is mild it may be a chance finding with little relevance to the patient’s presenting complaint, but such a finding should never be ignored. At the very least a follow-up blood count should be arranged. Anaemic patients have a low red cell count, a low haematocrit and a low haemoglobin, but some caveats need to be borne in mind: Red cell morphology, particularly the mean corpuscular volume (MCV), can help elucidate the cause of anaemia. The finding of a pancytopaenia suggests a problem in haematopoiesis, rather than haemolysis or blood loss. In women of childbearing age, assay of blood or urine β-HCG is important. The principles of management of haemorrhage are as follows: The indications for red cell transfusion are discussed in Chapter 13.5. The faster the onset of the anaemia, the greater the need for urgent replacement. Patients who are tolerating their anaemia may require no more than an appropriate diet with or without the addition of haematinics. Elderly patients with severe bleeding often need red cells urgently. Excessive administration of colloid and/or crystalloid precipitates left ventricular failure and it can then be difficult to administer red cells. The finding of a hypochromic microcytic anaemia on blood film is usually indicative of iron deficiency and, in the absence of an overt history of bleeding, should prompt the search for occult blood loss. Iron deficiency anaemia may be due to malnutrition, but inadequate dietary intake of iron is not usually the sole cause of anaemia in developed countries: much more commonly it is the result of chronic blood loss from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, the uterus or the renal tract. More unusual causes are haemoptysis and recurrent epistaxes. Patients present with insidious and rather vague symptoms. They may be unaware that they are bleeding and will probably show none of the trophic skin, nail and mucosal changes of iron deficiency. The automated cell count, in addition to showing a hypochromic, microcytic picture, may also show a raised red cell distribution width, which reflects anisocytosis on the blood film. Iron studies may confirm the diagnosis of iron deficiency without pointing to the underlying cause. Serum iron and ferritin are low and total iron-binding capacity is high. If the source of blood loss is obvious, for example heavy menstrual bleeding, then appropriate referral may be all that is indicated. If the source is not obvious, particularly in older patients, then sequential investigation of the GI tract and the renal tract may be indicated. Decisions to admit or discharge these patients depend on the red cell reserves, the patient’s cardiorespiratory status, home circumstances and the likelihood of compliance with follow up. The anaemia itself can be corrected with oral iron supplements: 200 mg of ferrous sulphate three times daily is an appropriate regimen, although single daily doses are often more acceptable to the patient and have fewer GI side effects. The finding of a raised MCV is common in the presence or absence of anaemia. Alcohol abuse is a frequent underlying cause and other causes are listed in Table 13.1.4. MCVs greater than 115 fL are usually due to megaloblastic anaemia which, in turn, is usually due to either vitamin B12 or folate deficiency. Vitamin B12 and folate are essential to DNA synthesis in all cells. Deficiencies manifest principally in red cell production because of the sheer number of red cells that are produced. B12 deficiency is usually the result of a malabsorption syndrome, whereas folate deficiency is of dietary origin. Tetrahydrofolate is a co-factor in DNA synthesis and, in turn, the formation of tetrahydrofolate from its methylated precursor is B12-dependent. Unabated cytoplasmic production of RNA in the context of impaired DNA synthesis appears to produce the enlarged nucleus and abundant cytoplasm of the megaloblast. These cells, when released to the periphery, have poor function and poor survival. Table 13.1.4 Some causes of a raised mass cell volume Alcohol Drugs Hypothyroidism Liver disease Megaloblastic anaemias (B12 and folate deficiency) Myelodysplasia Pregnancy Reticulocytosis B12 deficiency is an autoimmune disorder in which autoantibodies to gastric parietal cells and the B12 transport factor (intrinsic factor) interfere with B12 absorption in the terminal ileum. Patients have achlorhydria, mucosal atrophy (a painful smooth tongue) and, sometimes, evidence of other autoimmune disorders, such as vitiligo, thyroid disease and Addison’s disease. This is so-called ‘pernicious anaemia’. A rare, but important, manifestation of this disease is ‘subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord’. Demyelination of the posterior and lateral columns of the spinal cord manifests as a peripheral neuropathy and an abnormal gait. The central nervous system abnormalities worsen and become irreversible in the absence of B12 supplementation. Treatment of B12 deficient patients with folate alone may accelerate the onset of this condition. Undiagnosed untreated pernicious anaemia is not a common finding in the ED, but the laboratory finding of anaemia and megaloblastosis should prompt haematological consultation. The investigative work-up, which includes B12 and red cell folate levels, autoantibodies to parietal cells and intrinsic factor, a marrow aspirate, and Schilling’s test of B12 absorption, may well necessitate hospital admission. The work-up for folate deficiency is similar to that for B12. Occasionally, patients require investigation for a malabsorption syndrome (tropical sprue, coeliac disease), which includes jejunal biopsy. Folate deficiency is common in pregnancy because of the large folate requirements of the growing fetus. It can be difficult to diagnose because of the maternal physiological expansion of plasma volume and also of red cell mass, but diagnosis and treatment with oral folate supplements are important because of the risk of associated neural tube defects. Both B12 and folate deficiency are usually manifestations of chronic disease processes. Rarely, an acute megaloblastic anaemia and pancytopaenia can develop over the course of days and nitrous oxide therapy has been identified as a principal cause of this condition. Patients with chronic infective, malignant or connective tissue disorders can develop a mild-to-moderate normochromic normocytic anaemia. Evidence of bleeding or haemolysis is absent and there is no response to haematinic therapy. The pathophysiology of this anaemia is complex and probably involves both decreased red cell production and survival. Possible underlying mechanisms include reticuloendothelial overactivity in chronic inflammation and defects in iron metabolism mediated by a variety of acute-phase reactants and cytokines, such as interleukin-1, tumour necrosis factor and interferon γ, which impair renal erythropoietin production and function. Anaemia of chronic disorders (ACD) is generally not so severe as to warrant emergency therapy. The importance of ACD in the ED lies in its recognition as a pointer towards an underlying chronic process. Difficulties can arise in distinguishing ACD from iron deficiency and the two conditions may coexist – in rheumatoid arthritis, for example. Iron studies generally elucidate the nature of the anaemia. In iron deficiency, iron and ferritin are low and total iron binding is high, whereas in ACD iron and total iron binding are low and ferritin is normal or high. Bone marrow failure is rarely encountered in emergency medicine practice. The physician must be alert to the unusual, insidious or sinister presentation and be particularly attuned to the triad of decreased tissue oxygenation, immunocompromise and a bleeding diathesis that may herald a pancytopaenia. An FBC may dictate the need for haematological consultation, hospital admission and further investigation. Among the entities to be considered are the aplastic anaemias, characterized by a pancytopaenia secondary to failure of pluripotent myeloid stem cells. Half of cases are idiopathic, but important aetiologies are infections (e.g. non-A, non-B hepatitis), inherited diseases (e.g. Fanconi’s anaemia), irradiation, therapeutic or otherwise and, most important in the emergency setting, drugs. Drugs that have been implicated in the development of aplastic anaemia include, in addition to antimetabolites and alkylating agents, chloramphenicol, chlorpromazine and streptomycin. Characteristic of patients with a primary marrow failure is the absence of splenomegaly and the absence of a reticulocyte response. There is a correlation between prognosis and the severity of the pancytopaenia. Platelet counts less than 20×109/L and neutrophil counts less than 500/mL equate to severe disease. Depending on the severity of the accompanying anaemia, patients may require red cell and sometimes platelet transfusion in the ED, as well as broad-spectrum antibiotic cover. It is imperative to stop all medications that might be causing the marrow failure. Other forms of marrow failure include pure red cell aplasia, where marrow red cell precursors are absent or diminished. This can be a complication of haemolytic states in which a viral insult leads to an aplastic crisis (see haemolytic anaemias). The myelodysplastic syndromes are a group of disorders primarily affecting the elderly. In these states there is no reduction in marrow cellularity but the mature red cells, granulocytes and platelets generated from an abnormal clone of stem cells are disordered and dysfunctional. There is peripheral pancytopaenia. These disorders are classified according to observed cellular morphology (Table 13.1.5). These conditions were once termed ‘preleukaemia’ and one-third of patients progress to acute myeloid leukaemia. Table 13.1.5 Classification of the myelodysplastic syndromes Refractory anaemia Refractory anaemia with ringed sideroblasts Refractory anaemia with excess of blasts Chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia Two more causes of failure of erythropoiesis might be mentioned. One is due to invasion of the marrow and disruption of its architecture by extraneous tissue, the commonest cause being metastatic cancer. Finally, but not at all uncommon, is the anaemia of chronic renal failure, where deficient erythropoiesis is attributed to decreased production of erythropoietin. Most patients with chronic renal failure on dialysis treatment tolerate a moderate degree of anaemia, but occasionally require either transfusion or treatment with erythropoietin. Emergency physicians should recognize anaemia as a predictable entity in patients with chronic renal failure, usually not requiring any action. Patients whose main problem is haemolysis are encountered rarely in the ED. The most fulminant haemolytic emergency one could envisage is that following transfusion of ABO-incompatible blood (discussed in Chapter 13.5), a vanishingly rare event where proper procedures are followed. Haemolysis and haemolytic anaemia are occasionally encountered in decompensating patients with multisystem problems. Rarely, first presentations of unusual haematological conditions occur. Some of the haemolytic anaemias are hereditary conditions in which the inherited disorder is an abnormality intrinsic to the red cell, its membrane, its metabolic pathways or the structure of the haemoglobin contained in the cells. Such red cells are liable to be dysfunctional and to have increased fragility and a shortened lifespan. Lysis in the circulation may lead to clinical jaundice as bilirubin is formed from the breakdown of haemoglobin. Lysis in the reticuloendothelial system generally does not cause jaundice but may produce splenomegaly. The anaemia tends to be normochromic normocytic; sometimes a mildly raised MCV is due to an appropriate reticulocyte response from a normally functioning marrow. Serum bilirubin may be raised even in the absence of jaundice. Urinary urobilinogen and faecal stercobilinogen are detectable and serum haptoglobin is depleted. The antiglobulin (Coombs’) test is important in the elucidation of some haemolytic anaemias. In this test, red cells coated in vivo (direct test) or in vitro (indirect test) with IgG antibodies are washed to remove unbound antibodies, then incubated with an antihuman globulin reagent. The resultant agglutination is a positive test. Any chronic haemolytic process may be complicated by an ‘aplastic crisis’. This is usually a transient marrow suppression brought on by a viral infection which can result in a severe and life-threatening anaemia. Red cell transfusion in these circumstances may be life saving. A deficiency of the red cell wall protein, spectrin, leads to loss of deformability and increased red cell fragility. These cells are destroyed prematurely in the spleen. The condition may present at any age, with anaemia, intermittent jaundice and cholelithiasis. Patients are Coombs’ negative and show normal red cell osmotic fragility. Splenectomy radically improves general health. Hereditary elliptocytosis is a similar disease, with usually a milder course. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) generates reduced glutathione, which protects the red cell from oxidant stress. G6PD deficiency is an X-linked disorder present in heterozygous males and homozygous females. The disorder is commonly seen in West Africa, southern Europe, the Middle East and Southeast Asia. Oxidant stress leads to severe haemolytic anaemia. Precipitants include fava beans, antimalarial and analgesic drugs and infections. The enzyme deficiency can be demonstrated by direct assay and treatment is supportive. Whereas in the thalassaemias there is a deficiency in a given globin chain within the haemoglobin (Hb) molecule, in the haemoglobinopathies a given globin chain is present but structurally abnormal. HbS differs from normal HbA by one amino acid residue: valine replaces glutamic acid at the sixth amino acid from the N-terminus of the β-globin chain. Red cells containing HbS tend to ‘sickle’ at states of low oxygen tension. The deformed sickle-shaped red cell has increased rigidity, which causes it to lodge in the microcirculation and sequester in the reticuloendothelial system – the cause of a haemolytic anaemia. Sickle cell disease is encountered in Afro-Caribbean people. The higher incidence in tropical areas is attributed to the survival value of the β-S gene against falciparum malaria. Heterozygous individuals have ‘sickle trait’ and are usually asymptomatic. Homozygous (HbSS) individuals manifest the disease in varying degrees. The haemolytic anaemia is usually in the range of 60–100 g/L and can be well tolerated because HbS offloads oxygen to the tissues more efficiently than HbA. A patient with sickle cell disease may occasionally develop a rapidly worsening anaemia. This may be due to: In any of these circumstances, transfusion may be life saving. However, these events are unusual and more commonly encountered is the vaso-occlusive crisis. A stressor – for example infection, dehydration, or cold – causes sickle cells to lodge in the microcirculation. Bone marrow infarction is one well-recognized complication of the phenomenon, but virtually any body system can be affected. Common presenting complaints include acute spinal pain, abdominal pain (the mesenteric occlusion of ‘girdle sequestration’), chest pain (pulmonary vascular occlusion), joint pain, fever (secondary to tissue necrosis), neurological involvement (transient ischaemic attacks, strokes, seizures, obtundation, coma), respiratory embarrassment and hypoxia, priapism, ‘hand–foot syndrome’ (dactylitis of infancy), haematuria (nephrotic syndrome, papillary necrosis), skin ulcers of the lower limbs, retinopathies, glaucoma and gallstones. Most patients presenting with a vaso- occlusive crisis know they have the disease but, otherwise, the differential diagnosis is difficult. Sickle cells may be seen on the blood film and can also be induced by deoxygenating the sample. Hb electrophoresis can establish the type of Hb present. Other investigations are dictated by the presentation and may include blood cultures, urinalysis and culture, chest X-ray, arterial blood gases and electrocardiograph. Pain relief should commence early. A morphine infusion may be required for patients with severe ongoing pain. Other supportive measures are dictated by the presentation. Intravenous fluids are particularly important for patients with renal involvement. Aim to establish a urine output in excess of 100 mL/h in adults. Antibiotic cover may be required in the case of febrile patients with lung involvement. It may be impossible to differentiate between pulmonary vaso-occlusion and pneumonia. Many patients with sickle cell disease are effectively splenectomized owing to chronic splenic sequestration with infarction and are prone to infection from encapsulated bacteria. The choice of antibiotic depends on the clinical presentation. Indications for exchange transfusion are shown in Table 13.1.6. The efficacy of exchange transfusion in painful crises remains unproven. Table 13.1.6 Indications for exchange transfusion in sickle cell crisis Neurological presentations: TIAs, stroke, seizures Lung involvement (PaO2<65 mmHg with FiO2 60%) Sequestration syndromes Priapism Sickle trait or Hb S-C disease occurs in up to 10% in the black population. The clinical presentation resembles that of sickle cell disease but is usually less severe. In HbC, lysine replaces glutamic acid in the sixth position from the N terminus of the β-chain. Red cells containing HbC tend to be abnormally rigid, but the cells do not sickle. Homozygotes manifest a normocytic anaemia but there is no specific treatment and transfusion is seldom required. There is a high incidence of β-thalassaemia trait among people of Mediterranean origin although, in fact, the region of high frequency extends in a broad band east to Southeast Asia. Thalassaemias are disorders of haemoglobin synthesis. In the haemoglobin molecule, four haem molecules are attached to four long polypeptide globin chains. Four globin chain types (each with their own minor variations in amino acid order) are designated α, β, γ and δ. Haemoglobin A comprises two α and two β chains; 97% of adult haemoglobin is HbA. In thalassaemia, there is diminished or absent production of either the α chain (α-thalassaemia) or the β chain (β-thalassaemia). Most patients are heterozygous and have a mild asymptomatic anaemia, although the red cells are small. In fact, the finding of a marked microcytosis in conjunction with a mild anaemia suggests the diagnosis. There are four genes on paired chromosomes 16 coding for α-globin and two genes on paired chromosomes 11 coding for β-globin. α-Thalassaemias are associated with patterns of gene deletion as follows: (−/−) is Hb-Barts hydrops syndrome, incompatible with life and (α/-) is HbH disease. Patients who are heterozygous for β-thalassaemia have β-thalassaemia minor or thalassaemia trait. They are usually symptomless. Homozygous patients have β major. Diagnosis of the major clinical syndromes is usually possible through consideration of the presenting features in conjunction with an FBC, blood film and Hb electrophoresis. HbH disease patients present with moderate haemolytic anaemia and splenomegaly. The HbH molecule is detectable on electrophoresis and comprises unstable β tetramers. α Trait occurs with deletion of one or two genes. Hb, MCV and mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH) are low, but the patient is often asymptomatic. β major becomes apparent in the first 6 months of life with the decline of fetal Hb. There is a severe haemolytic anaemia, ineffective erythropoiesis, hepatosplenomegaly and failure to thrive. With improved care, many of these patients survive to adulthood and may possibly present to the ED, where transfusion could be life saving. Patients with β trait may be encountered in the ED relatively frequently. They are generally asymptomatic, with a mild hypochromic microcytic anaemia. It is important not to work-up these patients continually for iron deficiency and not to subject them to inappropriate haematinic therapy. Many of the acquired haemolytic anaemias are autoimmune in nature, a manifestation of a type II (cytotoxic) hypersensitivity reaction. Here, normal red cells are attacked by aberrant autoantibodies targeting antigens on the red cell membrane. These reactions may occur more readily at 37°C (warm autoimmune haemolytic anaemia, or AIHA), or at 4°C (cold AIHA). Warm AIHA is more common. Red cells are coated with IgG, complement or both. The cells are destroyed in the reticuloendothelial system. Fifty per cent of cases are idiopathic, but other recognized causes include lymphoproliferative disorders, neoplasms, connective tissue disorders, infections and drugs (notably methyldopa and penicillin). Patients have haemolytic anaemia, splenomegaly and a positive Coombs’ test. In the ED setting, it is important to stop any potentially offending drugs and search for the underlying disease. The idiopathic group may respond to steroids, other immunosuppressive or cytotoxic drugs or splenectomy. In cold AIHA, IgM attaches to the I red cell antigen in the cooler peripheries. Primary cold antibody AIHA is known as cold haemagglutinin disease. Other causes include lymphoproliferative disorders, infections such as mycoplasma, and paroxysmal cold haemoglobinuria. Patients sometimes manifest Reynaud’s disease and other manifestations of circulatory obstruction. Symptoms worsen in winter. Red cell lysis leads to haemoglobinuria. In this important group of conditions, intravascular haemolysis occurs in conjunction with a disorder of microcirculation. Important causes are shown in Table 13.1.7. Table 13.1.7 Causes of microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia Disseminated intravascular coagulation Haemolytic uraemic syndrome HELLP Malignancy Malignant hypertension Snake envenoming Thrombotic thrombocytopaenic purpura Vasculitis These are probably manifestations of the same pathological entity, with haemolytic uraemic syndrome occurring in children and thrombotic thrombocytopaenic purpura most commonly in the fourth decade, especially in women. The primary lesion is likely to be in the vascular endothelium. Fibrin and platelet microthrombi are laid down in arterioles and capillaries, possibly as an autoimmune reaction. The clotting system is not activated. Haemolytic anaemia, thrombocytopaenia and acute renal failure are sometimes accompanied by fever and neurological deficits. In adults, the presentation is usually one of a neurological disturbance (headache, confusion, obtundation, seizures or focal signs). The blood film reveals anaemia, thrombocytopaenia, reticulocytosis and schistocytes. Coombs’ test is negative. Patients require hospital admission. Adults with this condition may require aggressive therapy with prednisone, antiplatelet therapy, further immunosuppressive therapy and plasma exchange transfusions. HELLP stands for haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and a low platelet count and is seen in pregnant women in the context of pre-eclampsia. Treatment is as for pre-eclampsia, early delivery of the baby being of paramount importance. The introduction of procoagulants into the circulation resulting in the overwhelming of anticoagulant control systems may occur as a consequence of a substantial number of pathophysiological insults, obstetric, infective, malignant and traumatic. Disseminated intravascular coagulation has an intimate association with shock, from any cause. The widespread production of thrombin leads to deposition of microthrombi, bleeding secondary to thrombocytopaenia and a consumption coagulopathy, and red cell damage within abnormal vasculature leading to a haemolytic anaemia. Recognition of this condition prompts intensive care admission and aggressive therapy. Principles of treatment include definitive management of the underlying cause and, from the haematological point of view, replacement therapy that may involve transfusion of red cells, platelets, fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and cryoprecipitate. There may be a role for heparin and other anticoagulant treatments if specific tissue and organ survival is threatened by thrombus. This entity is unusual in that an intrinsic red cell defect is seen in the context of an acquired haemolytic anaemia. A somatic stem cell mutation results in a clonal disorder. A family of membrane proteins (CD55, CD59 and C8 binding protein) is deficient and renders cells prone to complement-mediated lysis. Because the same proteins are deficient in white cells and platelets, in addition to being anaemic, patients are prone to infections and haemostatic abnormalities. They may go on to develop aplastic anaemia or leukaemia. Treatment is supportive. Marrow transplant can be curative. Haemolysis may be due to mechanical trauma, as in ‘March haemoglobinuria’. Artificial heart valves can potentially traumatize red cells. Historically, ball-and-cage type valves have been most prone to cause haemolysis, whereas disc valves are more thrombogenic. Improvements in design have made cardiac haemolytic anaemia very rare. Haemolysis is sometimes seen in association with a number of infectious diseases, notably malaria. Other infections that have been implicated are listed in Table 13.1.8. Certain drugs and toxins are associated with haemolytic anaemia (Table 13.1.9). The haemolytic anaemia that is commonly seen in patients with severe burns is attributed to direct damage to the red cells by heat. Table 13.1.8 Infections associated with haemolysis Babesiosis Bartonella Clostridia Cytomegalovirus Coxsackie virus Epstein–Barr virus Haemophilus Herpes simplex HIV Malaria, especially Plasmodium falciparum (Blackwater fever) Measles Mycoplasma Varicella Table 13.1.9 Drugs and toxins associated with haemolysis Antimalarials Arsine (arsenic hydride) Bites: bees, wasps, spiders, snakes Copper Dapsone Lead (plumbism) Local anaesthetics: lidocaine, benzocaine Nitrates, nitrites Sulphonamides Mark Little Neutropaenia is defined as a decrease in the number of circulating neutrophils. The neutrophil count varies with age, sex and racial grouping. The severity of neutropaenia is usually graded as follows: The risk of infection rises as the neutrophil count falls and becomes significant once the neutrophil count drops below 1.0×109/L. Recent Australian guidelines have defined febrile neutropaenia as a patient with a temperature above 38.3°C (or above 38°C on two occasions) with a neutrophil count less than 0.5×109/L or with less than 1.0×109/L and likely to fall to less than 0.5×109/L. These patients need to be examined for signs of systemic compromise (Table 13.2.1). Table 13.2.1 Features of systemic compromise Systolic BP≤90 mmHg or≥30 mmHg below patients usual BP or inotropic support Room air arterial pO2≤60 mmHg ot SpO2<90% or need for mechanical ventilation Confusion or altered mental state Disseminated intravascular coagulation or abnormal PT/aPTT Cardiac failure or arrhythmia, renal failure, liver failure or any major organ failure (only if new or deteriorating and not AF or CHF) From Tam CS, OReilly M, Andersen D, et al. Use of empiric antimicrobial therapy in neutropenic fever. Int Med J 2011; 41:90-101. Neutropaenic patients are at greater risk of overwhelming infection if the onset of the neutropaenia is acute rather than chronic and, in the case of patients receiving cancer chemotherapy, if the absolute neutrophil count is in the process of falling rather than rising. Signs or symptoms of infection in the presence of severe neutropaenia, especially with features of systemic compromise, constitute a true emergency that mandates rapid assessment and aggressive management to prevent progression to overwhelming sepsis. In the emergency department (ED) setting, this is most commonly encountered when a patient presents with fever in the context of chemotherapy for cancer. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils are formed in marrow from the myelogenous cell series. Pluripotent haematopoietic stem cells are committed to a particular cell lineage through the formation of colony forming units, which further differentiate to form given white cell precursors. The mature neutrophil has a multilobed nucleus and granules in the cytoplasm. The cells are termed ‘neutrophilic’ because of the lilac colour of the granules caused by the uptake of both acidic and basic dyes. The neutrophils leave the marrow and enter the circulation, where they have a lifespan of only 6–10 h before entering the tissues. Here they migrate by chemotaxis to sites of infection and injury and then phagocytose and destroy foreign material. In health, about half of the available mature neutrophils are in the circulation. ‘Marginal’ cells are adherent to vascular endothelium or in the tissues and are not measured by the full blood count. Some individuals have fixed increased marginal neutrophil pools and decreased circulating pools; they are said to have benign idiopathic neutropaenia. For a previously normal individual to become neutropaenic there must be decreased production of neutrophils in the marrow, decreased survival of mature neutrophils or a redistribution of neutrophils from the circulating pool. The important causes are shown in Table 13.2.2. Table 13.2.2 Important causes of neutropaenia Decreased production Aplastic anaemia Leukaemias Lymphomas Metastatic cancer Drug-induced agranulocytosis Megaloblastic anaemias Vitamin B12 deficiency Folate deficiency CD8 and large granular lymphocytosis Myelodysplasic syndromes Decreased survival Idiopathic immune related Systemic lupus erythematosus Felty syndrome Drugs Redistribution Sequestration (hypersplenism) Increased utilization (overwhelming sepsis) Viraemia It is a defect in neutrophil production that is most likely to prove life threatening. Consumption of neutrophils in the periphery, as occurs early in infectious processes, is likely to be rapidly compensated for by a functioning marrow. Fortunately, most of the primary diseases of haematopoiesis are rare and, in practice, many of the acquired neutropaenias are drug induced. Processes interfering with haematopoiesis, often involving autoimmune mechanisms, may affect neutrophils both in the marrow and in the periphery. Some drugs cause neutropaenia universally but many more reactions are idiosyncratic, be they dose- related or independent of dose. Some commonly implicated drugs are listed in Table 13.2.3. Cancer chemotherapy drugs are now recognized as the commonest cause of neutropaenia. Table 13.2.3 Drugs commonly associated with neutropaenia Antibiotics: chloramphenicol, sulphonamides, isoniazid, rifampicin, β-lactams, carbenicillin Antidysrhythmic agents: quinidine, procainamide Antiepileptics: phenytoin, carbamazepine Antihypertensives: thiazides, ethacrynic acid, captopril, methyldopa, hydralazine Antithyroid agents Chemotherapeutic agents: especially methotrexate, cytosine arabinoside, 5-azacytidine, azathioprine, doxorubicin, daunorubicin, hydroxyurea, alkylating agents Connective tissue disorder agents: phenylbutazone, penicillamine, gold H2-receptor antagonists Phenothiazines, especially chlorpromazine Miscellaneous: imipramine, allopurinol, clozapine, ticlopidine, tolbutamide Neutropaenia is frequently anticipated based on the clinical presentation, such as fever developing in the context of cancer chemotherapy, by far the most common scenario in which severe neutropaenia is seen in the ED. Alternatively, it may be identified in the course of investigation for a likely infective illness or it might be an incidental finding during investigation for an unrelated condition. Chronic neutropaenia may be asymptomatic unless secondary or recurrent infections develop. Acute severe neutropaenia may present with fever, sore throat and mucosal ulceration or inflammation. Symptoms or signs of an associated disease process may also be present, such as pallor from anaemia or bleeding from thrombocytopaenia, as might occur in conditions causing pancytopaenia. The history of the mode of onset and duration of the illness is important. Systems enquiry may reveal cough, headache and photophobia, a diarrhoeal illness or urinary symptoms. The past history may reveal a known haematological illness or previous evidence of immunosuppression, such as frequent and recurrent infections. A detailed drug history is vital. Most neutropaenic drug reactions occur within the first 3 months of taking a drug. In the ED, vital signs, including pulse, blood pressure, temperature, respiratory rate and pulse oximetry, should be performed at initial assessment and monitored regularly until disposition. Attention should be paid to identifying early signs of severe sepsis and the progression to septic shock. Physical examination may reveal necrotizing mucosal lesions, pallor, petechial rashes, lymphadenopathy, bone tenderness, abnormal tonsillar or respiratory findings, spleno- or other organomegaly. Careful examination of the skin of the back, the lower limbs and the perineum for evidence of infection is important. The presence of indwelling venous access devices should be noted and insertion sites inspected for evidence of inflammation or infection. Investigation in the ED is first aimed at confirming and quantifying the severity of neutropaenia, identifying the cause and then at identifying the focus and severity of infection. An urgent full blood count and blood film should be ordered in any patient who is suspected of suffering febrile neutropaenia. A coagulation profile and biochemistry, including electrolytes and creatinine, serum lactate, glucose and liver function tests may be indicated once severe neutropaenia is confirmed. Anaemic patients may require a group-and-hold or cross-match. Microbiological cultures aimed at isolating a causative organism should be taken but antibiotics should not be unreasonably delayed in the presence of fever and confirmed significant neutropaenia. Blood cultures should be taken at the time of cannulation and, if possible, prior to the instigation of antibiotic therapy. Throat swab, swabs of skin lesions and indwelling venous access device sites, urinalysis and urine culture may be indicated depending on the clinical picture. Patients with apparent central nervous system infections might require a lumbar puncture, but this should be postponed or even cancelled in the presence of an uncorrected coagulopathy, signs of raised intracranial pressure, focal neurological signs or haemodynamic instability. Antibiotics, if clinically indicated, should be commenced prior to lumbar puncture. Management of the patient with confirmed febrile neutropaenia in the ED involves early recognition and treatment of bacterial infection and institution of supportive care to prevent progression to overwhelming sepsis and shock. Evolving or established haemodynamic instability requires immediate, aggressive resuscitation. Empiric broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy should be started in the ED after drawing blood for culture in any patient with fever and suspected or confirmed significant neutropaenia. This strategy has played a pivotal role in reducing mortality rates in febrile neutropaenia. Australian consensus-based clinical recommendations for the management of neutropaenic fever in adults were recently published. They reinforce the need for the administration of early antibiotics. In general, antibiotics should provide good cover for both Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms. With increased use of indwelling venous access devices for cancer chemotherapy, there has been an increase in the incidence of sepsis due to Gram-positive organisms, such as coagulase-negative staphylococci, S. aureus and methicillin-resistant Staph. aureus (MRSA). Although occurring infrequently, bacteraemia due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa is associated with a high morbidity and mortality and therefore should also be covered. Recent evidence has suggested that antibiotic monotherapy is as efficacious as combined therapy. Therefore, for clinically stable patients, Australian consensus guidelines recommend a beta lactam monotherapy (such as pipperacillin–tazobactam 4.5 g 6-hourly or cefepime 2 g 8-hourly or ceftazidime 2 g 8-hourly). These antibiotics should be administered within 1 hour of presentation and after at least one set of blood cultures. For patients with systemic compromise, the Australian consensus guidlelines recommend the above beta lactam antibiotics plus gentimicin (5–7 mg/kg daily) given within 30 minutes of presentation and after at least one set of blood cultures. If the clinicians believed the shocked patient was colonized with Gram-positive organisms (e.g. MRSA or has clinical evidence of a catheter-related infection in a unit with a high incidence of MRSA), then vancomycin (1.5 g 12-hourly if normal renal function) should be added. Empiric antifungal therapy is not generally required unless there is persistent fever in high-risk patients beyond 96 hour of antibacterial therapy. The presence of significant neutropaenia with fever generally mandates admission to hospital. Patients with severe acute neutropaenia without an established aetiology will also generally require admission regardless of the presence or absence of fever. Both the haematological abnormality and the likely presence of infection require investigation. Sometimes the aetiology of the neutropaenia will be evident; on other occasions marrow aspiration and biopsy will be required. There is emerging evidence that a subset of febrile neutropaenic patients can be identified who are at low risk of life-threatening complications and in whom duration of hospitalization and intensity of treatment may be safely reduced. Strategies that involve outpatient treatment of low-risk patients with oral antibiotics have also been evaluated. Such regimens are reliant upon accurate prediction of risk, as well as the availability of structured programmes and resources and are not yet in widespread use. The prognosis of the neutropaenic patient is largely dependent upon the underlying aetiology of the condition. Febrile neutropaenia has in the past been associated with a significant mortality rate which varies depending on the organism causing the infection. Improvements in therapy, such as rapid treatment with empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics, have significantly reduced mortality rates from this condition. Overall mortality rates for patients with febrile neutropaenia have reduced from more than 20% to less than 4% in recent data sets.

Haematology Emergencies

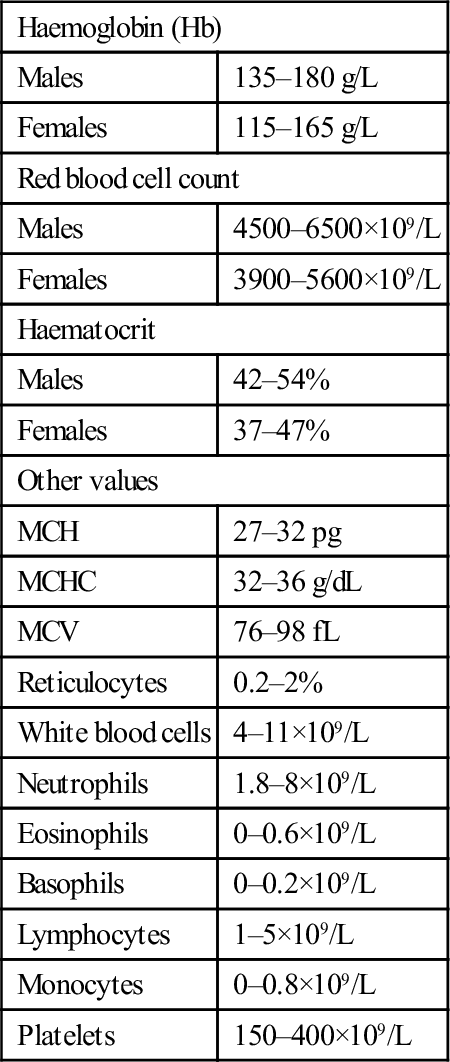

13.1 Anaemia

Introduction

Haemoglobin (Hb)

Males

135–180 g/L

Females

115–165 g/L

Red blood cell count

Males

4500–6500×109/L

Females

3900–5600×109/L

Haematocrit

Males

42–54%

Females

37–47%

Other values

MCH

27–32 pg

MCHC

32–36 g/dL

MCV

76–98 fL

Reticulocytes

0.2–2%

White blood cells

4–11×109/L

Neutrophils

1.8–8×109/L

Eosinophils

0–0.6×109/L

Basophils

0–0.2×109/L

Lymphocytes

1–5×109/L

Monocytes

0–0.8×109/L

Platelets

150–400×109/L

Anaemia secondary to haemorrhage

Aetiology

Clinical features

Clinical investigations

patients who are bleeding acutely may initially have a normal FBC

patients who are bleeding acutely may initially have a normal FBC

normal or high haematocrits may reflect haemoconcentration

normal or high haematocrits may reflect haemoconcentration

mixed pictures can be difficult to interpret, e.g. that of a polycythaemic patient who is bleeding.

mixed pictures can be difficult to interpret, e.g. that of a polycythaemic patient who is bleeding.

Treatment

Chronic haemorrhage

Disposition

Anaemia secondary to decreased red cell production

Megaloblastic anaemia

Anaemia of chronic disorders

Other causes of decreased red cell production

Anaemia secondary to decreased red cell survival: the haemolytic anaemias

Hereditary spherocytosis

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

Sickle cell anaemia

Haemoglobin S-C disease

Haemoglobin C disease

Thalassaemias

Acquired haemolytic anaemias

Microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia

Haemolytic uraemic syndrome and thrombotic thrombocytopaenic purpura

HELLP syndrome

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

Paroxysmal noctural haemoglobinuria

Other causes of haemolysis

13.2 Neutropaenia

Introduction

Pathophysiology and aetiology

Clinical features

Clinical investigations

Treatment

Disposition

Prognosis