Ectoderm

Surface barriers, such as enzymes and mucus, that are either directly antimicrobial or inhibit attachment of the microbe.

Surface barriers, such as enzymes and mucus, that are either directly antimicrobial or inhibit attachment of the microbe.

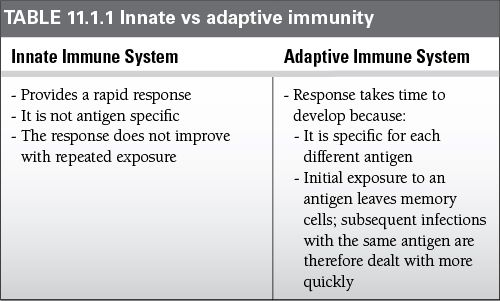

Any organism that breaks through this first barrier encounters the two further levels of defense, the innate and acquired immune responses.

Any organism that breaks through this first barrier encounters the two further levels of defense, the innate and acquired immune responses.

Innate (natural) responses

Innate (natural) responses

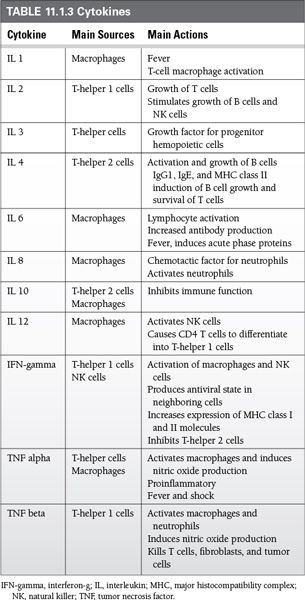

Use phagocytic cells (neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages) that release inflammatory mediators (basophils, mast cells, and eosinophils) and natural killer cells

Use phagocytic cells (neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages) that release inflammatory mediators (basophils, mast cells, and eosinophils) and natural killer cells

The molecular components of innate responses include complement, acute-phase proteins, and cytokines (i.e., interferons).

The molecular components of innate responses include complement, acute-phase proteins, and cytokines (i.e., interferons).

Acquired (adaptive) responses

Acquired (adaptive) responses

Acquired responses involve the proliferation of antigen-specific B and T cells, which occurs when the surface receptors of these cells bind to an antigen

Acquired responses involve the proliferation of antigen-specific B and T cells, which occurs when the surface receptors of these cells bind to an antigen

Specialized cells called antigen-presenting cells display the antigen to lymphocytes and collaborate with them in the response to the antigen.

Specialized cells called antigen-presenting cells display the antigen to lymphocytes and collaborate with them in the response to the antigen.

B cells secrete immunoglobulins (Ig), the antigen-specific antibodies (Ab) responsible for eliminating extracellular microorganisms.

B cells secrete immunoglobulins (Ig), the antigen-specific antibodies (Ab) responsible for eliminating extracellular microorganisms.

T cells help B cells make Ab and can also eradicate intracellular pathogens by activating macrophages and by killing virally infected cells.

T cells help B cells make Ab and can also eradicate intracellular pathogens by activating macrophages and by killing virally infected cells.

Lymph nodes, spleen, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue aka the secondary lymphoid tissues such as tonsils, adenoids, and Peyer’s patches defend mucosal surfaces.

Lymph nodes, spleen, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue aka the secondary lymphoid tissues such as tonsils, adenoids, and Peyer’s patches defend mucosal surfaces.

In the spleen and lymph nodes, the activation of lymphocytes by antigen occurs in distinctive B and T-cell compartments of lymphoid tissue.

In the spleen and lymph nodes, the activation of lymphocytes by antigen occurs in distinctive B and T-cell compartments of lymphoid tissue.

Diffuse collections of lymphoid cells are present throughout the lung and the lamina propria of the intestinal wall.

Diffuse collections of lymphoid cells are present throughout the lung and the lamina propria of the intestinal wall.

All these cells develop from pluripotent stem cells in the fetal liver and in the bone marrow and then circulate throughout the extracellular fluid.

All these cells develop from pluripotent stem cells in the fetal liver and in the bone marrow and then circulate throughout the extracellular fluid.

B cells reach maturity within the bone marrow.

B cells reach maturity within the bone marrow.

T cells must travel to the thymus to complete their development.

T cells must travel to the thymus to complete their development.

Immune Recognition

The T-cell and B-cell receptors have binding sites that are only 600 to 1,700 Å in size.

The T-cell and B-cell receptors have binding sites that are only 600 to 1,700 Å in size.

As a result, they only recognize a very small part of a complex antigen.

As a result, they only recognize a very small part of a complex antigen.

This small part is referred to as the epitope.

This small part is referred to as the epitope.

Only antigens that elicit an immune response are immunogenic.

Only antigens that elicit an immune response are immunogenic.

Small non-immunogenic antigens are called haptens and must be coupled to larger immunogenic molecules, termed carriers, to stimulate a response.

Small non-immunogenic antigens are called haptens and must be coupled to larger immunogenic molecules, termed carriers, to stimulate a response.

Carbohydrates must often be coupled to proteins in order to be immunogenic (i.e., polysaccharide antigens used in the Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine).

Carbohydrates must often be coupled to proteins in order to be immunogenic (i.e., polysaccharide antigens used in the Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine).

In autoimmune diseases (AD), there is no difference between the structure of self-antigens (autoantigens) and foreign antigens.

In autoimmune diseases (AD), there is no difference between the structure of self-antigens (autoantigens) and foreign antigens.

This is because lymphocytes have evolved to respond to antigens only in certain micro-environments such as those filled with inflammatory cytokines.

This is because lymphocytes have evolved to respond to antigens only in certain micro-environments such as those filled with inflammatory cytokines.

In AD, there are two types of pathologies.

In AD, there are two types of pathologies.

Those arising from an alteration in selection, regulation, or death of T or B cells (i.e., overly autoreactive B cells causing antinuclear and anti-DNA antibodies to be produced in systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]).

Those arising from an alteration in selection, regulation, or death of T or B cells (i.e., overly autoreactive B cells causing antinuclear and anti-DNA antibodies to be produced in systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]).

Some AD seem to reflect a loss of B-cell tolerance to an antigen in a once normal system (i.e., antiganglioside Ab causes Guillain–Barré syndrome).

Some AD seem to reflect a loss of B-cell tolerance to an antigen in a once normal system (i.e., antiganglioside Ab causes Guillain–Barré syndrome).

Genetic alterations on the effect of T cells or cytokine production often lead to inflammatory bowel disease.

Genetic alterations on the effect of T cells or cytokine production often lead to inflammatory bowel disease.

Genetic factors are crucial determinants of susceptibility to AD.

Genetic factors are crucial determinants of susceptibility to AD.

There is familial clustering and the rate of concordance is higher in monozygotic twins than in dizygotic twins.

There is familial clustering and the rate of concordance is higher in monozygotic twins than in dizygotic twins.

Most AD are multigenic.

Most AD are multigenic.

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) makes an important contribution to AD susceptibility.

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) makes an important contribution to AD susceptibility.

Most AD are linked to a particular class I or class II human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecule.

Most AD are linked to a particular class I or class II human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecule.

Cytokines

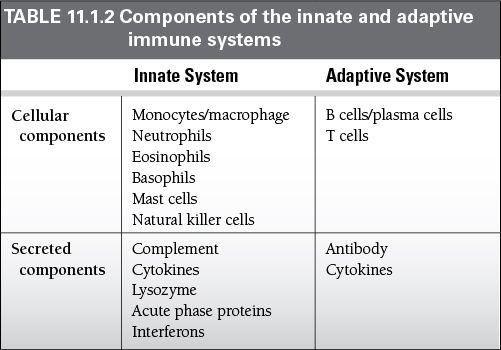

Cytokines are small, secreted proteins that act locally, via specific cell-surface receptors, as part of both the innate and adaptive immune response.

Cytokines are small, secreted proteins that act locally, via specific cell-surface receptors, as part of both the innate and adaptive immune response.

They have many effects, but in general they stimulate the immune response through

They have many effects, but in general they stimulate the immune response through

Growth, activation, and survival of various cells

Growth, activation, and survival of various cells

Increased production of surface molecules such as MHC

Increased production of surface molecules such as MHC

Some important cytokines and their main actions are shown in Table 11.1.3.

Some important cytokines and their main actions are shown in Table 11.1.3.

Autoimmune Diseases

20% of patients with AD admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) have their diagnosis made for the first time during the ICU admission.

20% of patients with AD admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) have their diagnosis made for the first time during the ICU admission.

10% to 25% of all patients with rheumatologic disorders visiting the emergency department require hospital admission, and up to one-third of the hospitalized patients need intensive care.

10% to 25% of all patients with rheumatologic disorders visiting the emergency department require hospital admission, and up to one-third of the hospitalized patients need intensive care.

These patients form only a small percentage of all ICU admissions.

These patients form only a small percentage of all ICU admissions.

The main cause for admission to the ICU in patients with autoimmune syndromes is respiratory dysfunction or failure.

The main cause for admission to the ICU in patients with autoimmune syndromes is respiratory dysfunction or failure.

Of all ICU admissions, SLE (33.5% of reported patients), rheumatoid arthritis (RA; 25%), and systemic vasculitis (15%) were the most frequent ADs in patients admitted to the ICU in the last decade.

Of all ICU admissions, SLE (33.5% of reported patients), rheumatoid arthritis (RA; 25%), and systemic vasculitis (15%) were the most frequent ADs in patients admitted to the ICU in the last decade.

Mortality ranged from 17% to 55% in case series including all ADs, but in the ones that only included patients with a specific AD, such as SLE, it reached up to 79%.

Mortality ranged from 17% to 55% in case series including all ADs, but in the ones that only included patients with a specific AD, such as SLE, it reached up to 79%.

High Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) score, multi-organ dysfunction, older age, and cytopenia were the most reported variables associated with mortality.

High Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) score, multi-organ dysfunction, older age, and cytopenia were the most reported variables associated with mortality.

Godeau et al. reported a series of 181 patients with autoimmune disorders where 41% of their patients were admitted for infections, 28% for exacerbation of their autoimmune condition, 15% had acute illnesses that were unrelated to their autoimmune disorders. Seven patients were admitted for drug-induced complications.

Godeau et al. reported a series of 181 patients with autoimmune disorders where 41% of their patients were admitted for infections, 28% for exacerbation of their autoimmune condition, 15% had acute illnesses that were unrelated to their autoimmune disorders. Seven patients were admitted for drug-induced complications.

Other studies of AD admitted to the ICU found 24% admitted for gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, 21% admitted for cardiac conditions, 21% for pneumonia, 18% for sepsis, 13% for interstitial lung disease, 5% for seizures, and 5% with cerebral hemorrhage.

Other studies of AD admitted to the ICU found 24% admitted for gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, 21% admitted for cardiac conditions, 21% for pneumonia, 18% for sepsis, 13% for interstitial lung disease, 5% for seizures, and 5% with cerebral hemorrhage.

A significant number of patients may have acute illness unrelated to the autoimmune condition but their condition still influences the outcome of the acute illness.

A significant number of patients may have acute illness unrelated to the autoimmune condition but their condition still influences the outcome of the acute illness.

Systemic Effects of Autoimmune Disease

Respiratory System

Respiratory failure is the most common diagnosis in patients with SLE in ICU.

Respiratory failure is the most common diagnosis in patients with SLE in ICU.

This is mostly due to the disease itself as well as the increased propensity for community and opportunistic infections.

This is mostly due to the disease itself as well as the increased propensity for community and opportunistic infections.

Common respiratory complaints are shortness of breath, cough, hemoptysis, chest pain, and stridor.

Common respiratory complaints are shortness of breath, cough, hemoptysis, chest pain, and stridor.

Shortness of breath is usually associated with hypoxia secondary to direct pulmonary parenchymal involvement in SLE, RA, scleroderma, and Goodpasture’s syndrome.

Shortness of breath is usually associated with hypoxia secondary to direct pulmonary parenchymal involvement in SLE, RA, scleroderma, and Goodpasture’s syndrome.

Hemoptysis may also occur in patients with systemic vasculitides and Goodpasture’s syndrome.

Hemoptysis may also occur in patients with systemic vasculitides and Goodpasture’s syndrome.

This occurs by diffuse alveolar damage which may progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

This occurs by diffuse alveolar damage which may progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage can be a catastrophic event.

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage can be a catastrophic event.

Patients present with hemoptysis, anemia, pulmonary infiltrates on radiographic imaging, and respiratory failure.

Patients present with hemoptysis, anemia, pulmonary infiltrates on radiographic imaging, and respiratory failure.

The diagnosis is confirmed by serial bronchoalveolar lavage.

The diagnosis is confirmed by serial bronchoalveolar lavage.

This can be caused by antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides, SLE, Goodpasture, mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD), scleroderma, polymyositis, and RA.

This can be caused by antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides, SLE, Goodpasture, mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD), scleroderma, polymyositis, and RA.

Stridor may develop in patients secondary to airway obstruction at the level of the vocal cords, subglottic region, or the trachea.

Stridor may develop in patients secondary to airway obstruction at the level of the vocal cords, subglottic region, or the trachea.

This can occur in Wegener’s granulomatosis, relapsing polychondritis, or RA.

This can occur in Wegener’s granulomatosis, relapsing polychondritis, or RA.

Tracheal intubation is often difficult in these patients due to the upper airway stenoses as well as the associated arthropathy often present in the cervical spine and, as a result, fiberoptic intubation may be preferred.

Tracheal intubation is often difficult in these patients due to the upper airway stenoses as well as the associated arthropathy often present in the cervical spine and, as a result, fiberoptic intubation may be preferred.

Chest pain is usually pleuritic and may suggest pleural involvement in diseases such as SLE; however, vigilance should be maintained regarding PE.

Chest pain is usually pleuritic and may suggest pleural involvement in diseases such as SLE; however, vigilance should be maintained regarding PE.

A significant number of patients with AD admitted to the ICU have chronic interstitial pulmonary fibrosis.

A significant number of patients with AD admitted to the ICU have chronic interstitial pulmonary fibrosis.

This tends to occur in patients with RA and scleroderma.

This tends to occur in patients with RA and scleroderma.

Respiratory failure may soon follow even with mild pulmonary infections.

Respiratory failure may soon follow even with mild pulmonary infections.

Coexisting inflammatory or corticosteroid-induced myopathy may further compromise respiratory reserve in these patients.

Coexisting inflammatory or corticosteroid-induced myopathy may further compromise respiratory reserve in these patients.

Due to these manifestations, >60% of these patients require mechanical ventilation.

Due to these manifestations, >60% of these patients require mechanical ventilation.

Respiratory muscle weakness may be present in many patients.

Respiratory muscle weakness may be present in many patients.

Polymyositis and dermatomyositis commonly involve the respiratory muscles.

Polymyositis and dermatomyositis commonly involve the respiratory muscles.

Patients may not be able to protect their airway and may need intubation to prevent aspiration.

Patients may not be able to protect their airway and may need intubation to prevent aspiration.

Intercostal weakness may also lead to respiratory failure.

Intercostal weakness may also lead to respiratory failure.

Corticosteroids are the drugs most commonly used for immunosuppression in patients with rheumatologic disorders; proximal muscle weakness can be common.

Corticosteroids are the drugs most commonly used for immunosuppression in patients with rheumatologic disorders; proximal muscle weakness can be common.

If serum creatinine phosphokinase as well as erythrocyte sedimentation rates (ESR) are elevated, this distinguishes inflammatory from steroid-induced weakness.

If serum creatinine phosphokinase as well as erythrocyte sedimentation rates (ESR) are elevated, this distinguishes inflammatory from steroid-induced weakness.

A rare shrinking-lung syndrome has been described in patients with SLE, characterized by small lung fields and elevation of the diaphragm.

A rare shrinking-lung syndrome has been described in patients with SLE, characterized by small lung fields and elevation of the diaphragm.

Weakness of the diaphragm without involvement of other muscles has been implicated as a cause of this syndrome.

Weakness of the diaphragm without involvement of other muscles has been implicated as a cause of this syndrome.

Cardiovascular System

Hypertension is the most common cardiovascular manifestation of rheumatologic diseases, but it is rarely severe enough to warrant emergent treatment.

Hypertension is the most common cardiovascular manifestation of rheumatologic diseases, but it is rarely severe enough to warrant emergent treatment.

Malignant hypertension associated with microangiopathic anemia and acute renal failure (ARF) occurs in a significant number of patients with scleroderma 2 to 3 years after the onset of skin manifestations.

Malignant hypertension associated with microangiopathic anemia and acute renal failure (ARF) occurs in a significant number of patients with scleroderma 2 to 3 years after the onset of skin manifestations.

Acute left ventricular failure caused by myocarditis is common in patients with SLE.

Acute left ventricular failure caused by myocarditis is common in patients with SLE.

This diagnosis is often missed because of its coexistence with other organ dysfunction such as lupus nephritis and autoimmune hemolytic anemia.

This diagnosis is often missed because of its coexistence with other organ dysfunction such as lupus nephritis and autoimmune hemolytic anemia.

Cardiac arrhythmias may also occur as the result of myocarditis.

Cardiac arrhythmias may also occur as the result of myocarditis.

Coronary arteritis may occur in some systemic vasculitides and produce angina or acute myocardial infarction (MI).

Coronary arteritis may occur in some systemic vasculitides and produce angina or acute myocardial infarction (MI).

This is particularly common in children with Kawasaki disease.

This is particularly common in children with Kawasaki disease.

In young adults, coronary arteries may be affected in polyarteritis nodosa or SLE.

In young adults, coronary arteries may be affected in polyarteritis nodosa or SLE.

MI can occur in the absence of arteritis in the antiphosholipid syndrome.

MI can occur in the absence of arteritis in the antiphosholipid syndrome.

Women between 35 and 44 years of age with SLE are 50 times more likely to develop MI than age-matched controls, likely due to premature atherosclerosis in damaged coronary arteries, the use of steroids, and premature menopause.

Women between 35 and 44 years of age with SLE are 50 times more likely to develop MI than age-matched controls, likely due to premature atherosclerosis in damaged coronary arteries, the use of steroids, and premature menopause.

Pericarditis is seen in 23% of patients with SLE but cardiac tamponade is uncommon.

Pericarditis is seen in 23% of patients with SLE but cardiac tamponade is uncommon.

SLE also may cause mitral valve regurgitation and Libman–Sacks endocarditis, both of which can be life threatening.

SLE also may cause mitral valve regurgitation and Libman–Sacks endocarditis, both of which can be life threatening.

Aortic root dilatation with aneurysm formation with or without aortic regurgitation occurs only in advanced stages of ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s syndrome, and RA.

Aortic root dilatation with aneurysm formation with or without aortic regurgitation occurs only in advanced stages of ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s syndrome, and RA.

The aorta is also the predominant site of involvement in aortoarteritis (Takayasu’s disease) and this may affect the proximal branches (i.e., carotid, subclavian).

The aorta is also the predominant site of involvement in aortoarteritis (Takayasu’s disease) and this may affect the proximal branches (i.e., carotid, subclavian).

Hypertension may be present in more than 50% of patients and may be missed if the blood pressure is recorded in the upper limbs.

Hypertension may be present in more than 50% of patients and may be missed if the blood pressure is recorded in the upper limbs.

Cerebrovascular insufficiency is common and may result in retinopathy or stroke.

Cerebrovascular insufficiency is common and may result in retinopathy or stroke.

Renal System

10% to 35% of patients with systemic AD admitted to ICU have abnormal renal function.

10% to 35% of patients with systemic AD admitted to ICU have abnormal renal function.

Common causes are RA, lupus nephritis, and necrotizing vasculitis.

Common causes are RA, lupus nephritis, and necrotizing vasculitis.

ARF and rapidly progressive renal failure are the most common manifestations, although occasionally patients may present with simple hematuria.

ARF and rapidly progressive renal failure are the most common manifestations, although occasionally patients may present with simple hematuria.

Mechanisms for renal failure in these patients include renal artery occlusion (aortoarteritis), microangiopathy (scleroderma, RA with vasculitis, Sjogren’s), acute glomerulonephritis (SLE), crescentic glomerulonephritis (polyarteritis nodosa, Wegener’s granulomatosis, SLE, and Goodpasture’s), and rarely tubulointerstitial nephritis (SLE, Sjogren’s).

Mechanisms for renal failure in these patients include renal artery occlusion (aortoarteritis), microangiopathy (scleroderma, RA with vasculitis, Sjogren’s), acute glomerulonephritis (SLE), crescentic glomerulonephritis (polyarteritis nodosa, Wegener’s granulomatosis, SLE, and Goodpasture’s), and rarely tubulointerstitial nephritis (SLE, Sjogren’s).

Scleroderma renal crisis occurs in 15% of patients with systemic sclerosis.

Scleroderma renal crisis occurs in 15% of patients with systemic sclerosis.

It is a medical emergency and presents with an abrupt onset of hypertension and ARF.

It is a medical emergency and presents with an abrupt onset of hypertension and ARF.

This diagnosis is confirmed with demonstration of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia.

This diagnosis is confirmed with demonstration of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia.

Treatment should be early with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor such as captopril and lisinopril blood pressure control.

Treatment should be early with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor such as captopril and lisinopril blood pressure control.

Plasma exchange can be considered.

Plasma exchange can be considered.

It can take up to 3 years for the kidney function to improve.

It can take up to 3 years for the kidney function to improve.

Nervous System

Neurologic manifestations are present in 10% to 20% of patients presenting to the ICU.

Neurologic manifestations are present in 10% to 20% of patients presenting to the ICU.

Seizures and psychosis are particularly common in patients with SLE during the course of the illness.

Seizures and psychosis are particularly common in patients with SLE during the course of the illness.

Seizures may also occur in patients with thrombosis of the cerebral veins and dural sinuses, conditions commonly seen in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome or SLE with lupus anticoagulant.

Seizures may also occur in patients with thrombosis of the cerebral veins and dural sinuses, conditions commonly seen in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome or SLE with lupus anticoagulant.

Brain imaging and cerebrospinal fluid examination are necessary in order to rule out an infective cause.

Brain imaging and cerebrospinal fluid examination are necessary in order to rule out an infective cause.

Central nervous system (CNS) lupus carries a poor short-term prognosis and is an indication for aggressive immunosuppressive therapy.

Central nervous system (CNS) lupus carries a poor short-term prognosis and is an indication for aggressive immunosuppressive therapy.

Cerebral infarction is the next most common neurologic manifestation and usually results from arterial thrombosis.

Cerebral infarction is the next most common neurologic manifestation and usually results from arterial thrombosis.

It occurs in 5% of patients with SLE but may also occur in patients with temporal arteritis, aortoarteritis (Takayasu’s), polyarteritis nodosa, and other vasculitides.

It occurs in 5% of patients with SLE but may also occur in patients with temporal arteritis, aortoarteritis (Takayasu’s), polyarteritis nodosa, and other vasculitides.

Cerebral venous thrombosis is often seen in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome and SLE with lupus anticoagulant factor.

Cerebral venous thrombosis is often seen in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome and SLE with lupus anticoagulant factor.

Intracranial hemorrhage is common and has been reported in up to 7% of patients with SLE.

Intracranial hemorrhage is common and has been reported in up to 7% of patients with SLE.

Some cases have also been reported in CNS vasculitis, scleroderma, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and Behçet’s disease.

Some cases have also been reported in CNS vasculitis, scleroderma, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and Behçet’s disease.

Gastrointestinal System

GI manifestations are encountered in approximately 30% of ICU patients.

GI manifestations are encountered in approximately 30% of ICU patients.

Hemorrhage is the most common GI manifestation in patients with AD.

Hemorrhage is the most common GI manifestation in patients with AD.

Hematemesis is usually caused by acute erosive gastritis or gastric and duodenal ulcers in patients with RA or SLE secondary to treatment with steroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Hematemesis is usually caused by acute erosive gastritis or gastric and duodenal ulcers in patients with RA or SLE secondary to treatment with steroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

In patients with Henoch–Schönlein purpura, systemic sclerosis or necrotizing vasculitis, bleeding from ischemic ulceration of the small intestinal or colonic mucosa may produce hematochezia.

In patients with Henoch–Schönlein purpura, systemic sclerosis or necrotizing vasculitis, bleeding from ischemic ulceration of the small intestinal or colonic mucosa may produce hematochezia.

Thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy often present in AD may aggravate bleeding from pre-existing GI ulcers.

Thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy often present in AD may aggravate bleeding from pre-existing GI ulcers.

Complications resulting from GI ischemia occur in 10% of patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Complications resulting from GI ischemia occur in 10% of patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis.

It is also seen in patients with RA, SLE, polyarteritis nodosa, Behçet’s, and Henoch–Schönlein purpura.

It is also seen in patients with RA, SLE, polyarteritis nodosa, Behçet’s, and Henoch–Schönlein purpura.

Manifestations of GI ischemia depend on the size of the involved vessels.

Manifestations of GI ischemia depend on the size of the involved vessels.

Large-vessel involvement causes mesenteric ischemia.

Large-vessel involvement causes mesenteric ischemia.

Medium-sized vessel involvement typically seen in Wegener’s granulomatosis, polyarteritis nodosa, and other necrotizing vasculitides may cause hemorrhage from rupture of aneurysms or intestinal angina.

Medium-sized vessel involvement typically seen in Wegener’s granulomatosis, polyarteritis nodosa, and other necrotizing vasculitides may cause hemorrhage from rupture of aneurysms or intestinal angina.

Prolonged use of corticosteroids, NSAIDs, or pre-existing pathology such as diverticular disease can increase the chances of GI perforation in these patients.

Prolonged use of corticosteroids, NSAIDs, or pre-existing pathology such as diverticular disease can increase the chances of GI perforation in these patients.

Some with scleroderma or SLE have a visceral smooth muscle myopathy that can present with intestinal pseudo-obstruction.

Some with scleroderma or SLE have a visceral smooth muscle myopathy that can present with intestinal pseudo-obstruction.

Some patients with Henoch–Schönlein purpura have severe intestinal ischemic manifestations with bleeding, infarction, perforation, and intussusception.

Some patients with Henoch–Schönlein purpura have severe intestinal ischemic manifestations with bleeding, infarction, perforation, and intussusception.

Acute pancreatitis has been reported in association with SLE, Henoch–Schönlein purpura, and Kawasaki’s disease.

Acute pancreatitis has been reported in association with SLE, Henoch–Schönlein purpura, and Kawasaki’s disease.

A combination of vasculitis, autoimmunity, and drug toxicity has been proposed as a possible mechanism.

A combination of vasculitis, autoimmunity, and drug toxicity has been proposed as a possible mechanism.

Peritonitis without infection or perforation may occur in SLE, RA, Still’s disease, and familial Mediterranean fever.

Peritonitis without infection or perforation may occur in SLE, RA, Still’s disease, and familial Mediterranean fever.

Hepatic dysfunction with elevation of serum transaminase levels occurs in 40% to 70% of patients with Still’s disease and in some patients with SLE and polyarteritis nodosa.

Hepatic dysfunction with elevation of serum transaminase levels occurs in 40% to 70% of patients with Still’s disease and in some patients with SLE and polyarteritis nodosa.

It may also result from the use of drugs such as NSAIDs and methotrexate (MTX).

It may also result from the use of drugs such as NSAIDs and methotrexate (MTX).

Fulminant hepatic failure is rare but may occur in some patients with Still’s disease or RA.

Fulminant hepatic failure is rare but may occur in some patients with Still’s disease or RA.

It can also be caused by associated medications such as sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine.

It can also be caused by associated medications such as sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine.

Hematologic Disorders

Anemia of chronic diseases is seen especially in RA and SLE.

Anemia of chronic diseases is seen especially in RA and SLE.

The hemoglobin in these patients rarely drops below 8 g/L.

The hemoglobin in these patients rarely drops below 8 g/L.

Anemia of chronic disease can be distinguished from anemia of chronic blood loss by reduced serum iron-binding capacity and serum iron, although the ratio of iron to iron-binding capacity remains normal.

Anemia of chronic disease can be distinguished from anemia of chronic blood loss by reduced serum iron-binding capacity and serum iron, although the ratio of iron to iron-binding capacity remains normal.

Serum ferritin levels are normal or increased.

Serum ferritin levels are normal or increased.

Severe autoimmune hemolytic anemia may occur in some patients with SLE.

Severe autoimmune hemolytic anemia may occur in some patients with SLE.

Thrombocytopenia is usually caused by autoimmune platelet destruction and is present in one-third of patients with SLE.

Thrombocytopenia is usually caused by autoimmune platelet destruction and is present in one-third of patients with SLE.

Thrombocytopenia may also be seen as a feature of the antiphospholipid syndrome.

Thrombocytopenia may also be seen as a feature of the antiphospholipid syndrome.

Bleeding caused by Ab against factor VIII is the most common autoimmune coagulation disorder and is seen in SLE and RA.

Bleeding caused by Ab against factor VIII is the most common autoimmune coagulation disorder and is seen in SLE and RA.

Bleeding in these patients does not respond to replacement therapy, but porcine factor VIII, which is antigenically different from human factor VIII, may help.

Bleeding in these patients does not respond to replacement therapy, but porcine factor VIII, which is antigenically different from human factor VIII, may help.

Also, immunosuppression with corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, and azathioprine (AZ) has been tried with some success.

Also, immunosuppression with corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, and azathioprine (AZ) has been tried with some success.

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is extremely effective in the short term.

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is extremely effective in the short term.

Lupus anticoagulant prolongs the prothrombin time but usually does not cause bleeding; it produces spontaneous thrombosis.

Lupus anticoagulant prolongs the prothrombin time but usually does not cause bleeding; it produces spontaneous thrombosis.

Rarely thrombocytopenia may occur as a part of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in patients with RA, scleroderma, polymyositis, or MCTD and in patients with SLE.

Rarely thrombocytopenia may occur as a part of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in patients with RA, scleroderma, polymyositis, or MCTD and in patients with SLE.

Leukopenia is seen in patients with Felty’s syndrome, Sjogren’s syndrome, and in up to 50% of patients with active SLE.

Leukopenia is seen in patients with Felty’s syndrome, Sjogren’s syndrome, and in up to 50% of patients with active SLE.

May also occur as a side effect of commonly used drugs such as NSAIDs and immunosuppressive agents

May also occur as a side effect of commonly used drugs such as NSAIDs and immunosuppressive agents

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree