BRIEF HISTORY OF OUTCOMES AND QUALITY

Although Florence Nightingale (1820 to 1910) is best known as the founder of modern nursing, she also made significant contributions as a social reformer and statistician. She collected data about the Crimean War and analyzed the data to support her request for resources to alleviate the deplorable conditions in the hospital. The statistical evidence from Nightingale’s mortality rates in civilian and military hospitals showed the unsanitary living conditions leading to endemic diseases. The first reported systematic use of patient outcomes to evaluate health care is attributed to Nightingale who recorded and analyzed health care conditions and patient outcomes during the Crimean War of 1853 to 1856 (Lang & Marek, 1990; Mitchell, Heinrich, Moritz, & Hinshaw, 1997). Her carefully recorded details and analysis established her as the first statistician of her time and the first reformer for quality health care.

Ernest Codman, MD, (1869 to 1940) was a Boston surgeon who was a Harvard Medical School graduate, member of the surgical staff at Massachusetts General Hospital, and faculty member at Harvard. By 1905, Codman was carrying small cards, known as end result ideas, for all his patients/surgeries to which he added notes about how he might improve the care in the future by systematically following the progress of patients through recovery. His interest in quality led him to examine provider competency. In 1914, the hospital refused his request to evaluate surgeon competency, and his staff privileges were revoked. The notion that quality could be improved was heresy a century ago (Mallon, 2000). Without staff privileges, he had no place to practice. Coming from a family of wealth, Codman established his own hospital and published his own end results in a privately published book. With his fervent interest in health care quality, he was a leader in founding the American College of Surgeons and its Hospital Standardization Program, which eventually became Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, now called The Joint Commission (TJC). An advocate for hospital reform, he crusaded to have the Massachusetts Medical Society publish a summary of his end notes in their publication, the New England Journal of Medicine. The request was denied. The Codman Award, the prestigious annual award for quality and safety from TJC, bears his name. Codman’s work is now recognized as the beginning of quality, transparency, patient centeredness, and outcomes management (Mallon, 2000).

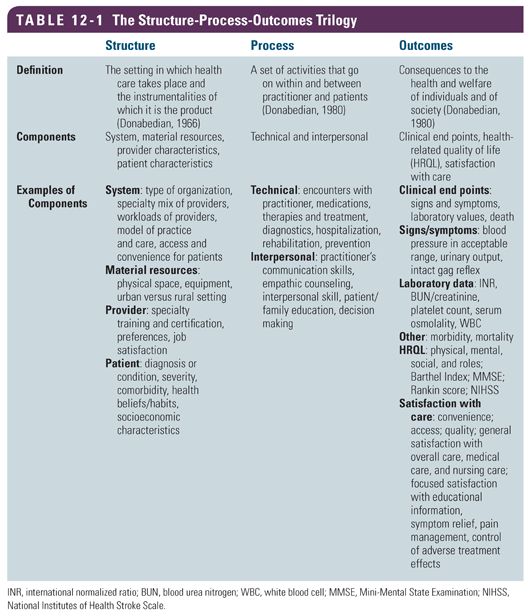

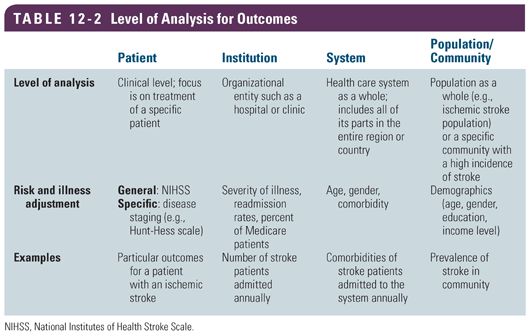

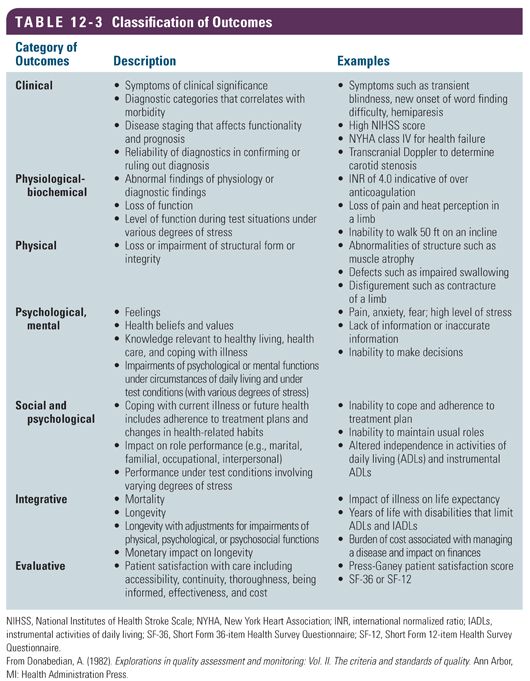

Quality and outcomes in health care lay dormant for the next 50 years until Avedis Donabedian (1919 to 2000) assumed the gauntlet. Donabedian was a physician and researcher at the University of Michigan and founder of the study of quality in health care and medical outcomes research. In 1966, he developed a conceptual model that provides a framework for examining health services and evaluating the quality of care (Donabedian, 1966). According to his model, information about the quality of care can be drawn from the three categories of structure, process, and outcomes. Structure is defined as the settings in which health care takes place and the instrumentalities of which it is the product (Donabedian, 1980). It is the conditions under which care is provided including material resources, human resources, and organizational characteristics. Process refers to a set of activities that go on within and between practitioners and patients (Donabedian, 1980). It is the activities encompassing health care such as diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation, and prevention as well as the interpersonal components such as education, counseling, decision making, and other aspects of communications. Outcome is defined as the consequences to the health and welfare of individuals and of society (Donabedian, 1980); it is a change in a patient’s current and future health that can be attributed to some alteration in delivery of health care (Table 12-1). The level of analysis for outcomes can be at the individual patient, organization, system, or population/community level (Table 12-2). Donabedian (1982) classified outcomes into the categories of clinical, physiological-biochemical, physical, psychological (mental), social and psychological, integrative, and evaluative outcomes (Table 12-3). This comprehensive list of outcome categories can be applied at a variety of settings and levels of analysis. Although cost is listed in the Donabedian evaluative outcomes category, it is an area that has gained major prominence because the cost of health care has escalated and is out of control; thus, economic outcomes merit further discussion in this chapter. The Donabedian model continues to be the dominant framework and paradigm for assessing quality of health care.

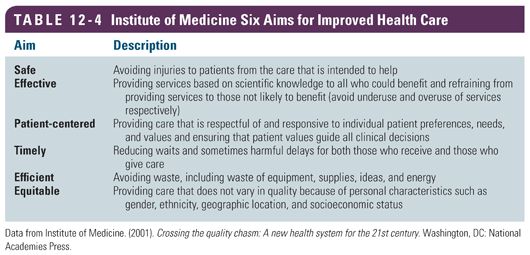

Outcomes at the system level of health care are also described. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century (IOM, 2001), called for a fundamental reform of health care to ensure that all Americans receive care that is safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable. These six aims are designed to improve the delivery of care and improve patient outcomes (Table 12-4). The report further notes that care should be based on the strongest clinical evidence and be provided in a technically and culturally competent manner with good communication and shared decision making (IOM, 2001). The six aims are often cited as outcome criteria for quality of health care.

Another systems framework often mentioned as criteria for evaluating outcomes of health care is the “Triple Aim” model (Berwick, Nolan, & Whittington, 2008). The Triple Aim model is a framework developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) that describes an approach to optimizing health system performance. The IHI believes that new models must be developed to simultaneously pursue these three dimensions, called the Triple Aim, which includes improving the patient’s experience of care (including quality and satisfaction), improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita cost of health care (Berwick et al., 2008). This framework has become the organizing framework for the National Quality Strategy of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and for strategies of other public and private health organization such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Premier, and the Commonwealth Fund (Stiefel & Nolan, 2012). The IHI has worked on finding ways to operationalize and measure these outcomes. The Guide to Measuring the Triple Aim: Population Health, Experience of Care, and Per Capita Cost (Stiefel & Nolan, 2012) is available for those interested in learning more about measuring outcomes at the system level.

MEASURES AND MEASUREMENT

MEASURES AND MEASUREMENT

The terminology used to discuss measures and measurement is confusing in that terms such as measure, indicator, metric, and outcome are used interchangeably. A measure (noun) is an instrument, tool, or discrete entity (e.g., age, gender) used for measuring, recording, or monitoring some form of information; for setting a standard as a basis for comparison; and as an indicator of performance, that is, a reference point against which another something can be evaluated. To measure (verb) is to bring into comparison against a standard (National Quality Forum [NQF], n.d.-b). An indicator is observable and measurable evidence of the effect of some intervention or action on the recipient (Ingersoll, 2009). It is a device, instrument, or other entity for measuring, recording, and monitoring some type of information, that is, a measurement tool. An indicator may be further defined by terms such as quality indicator, clinical indicator, and economic indicator for greater specificity. Although the word metric is more expansive than the terms measure and indicator, the terms are often used interchangeably in health care measurement.

National organizations have developed sets of quality indicators. For example, the quality indicators developed and maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) respond to the need for multidimensional and accessible quality measures that can be used to gage performance in health care. These quality indicators are evidence-based and can be used to identify variations in the quality of care provided by both inpatient and outpatient facilities. These measures are currently organized as four modules: the prevention quality indicators (PQIs), the inpatient quality indicators (IQIs), the patient safety indicators (PSIs), and the pediatric quality indicators (PDIs). They are available at the AHRQ website (Quality initiatives, n.d.). According to Donabedian (1966), an outcome is the end point, result, or consequence of care. Some authors use terms such as structural outcomes or process outcomes; however, these are structural measures and process measures. The term outcome is reserved to reflect the intent of the Donabedian (1966) definition. A further discussion of measure outcomes is provided in the following text.

Types of Measures

All measures are reflective of some level of performance. Performance measures include measures of health care processes, patient outcomes, patient perceptions of care, and organizational structure and systems associated with the ability to provide high-quality care. Standardized performance measures are those measures with detailed specification (e.g., definitions of the numerator and denominator, sampling strategy, if appropriate) that allow for comparison of like data. Collected data sometimes requires risk adjustment or stratification of results across key subgroups for better interpretation of data. Risk adjustment is a process that modifies the analysis of performance measurement results by those element of the patient population that affect results, but are out of the control of providers, and are likely to be common and not randomly distributed (IOM, 2006). In practice, variance in outcomes across settings is common and may require risk adjustment.

Some measures have a narrow focus examining discrete performance in conducting specific tasks such as beginning antithrombotic drug therapy within 48 hours of an ischemic stroke. Other measures provide a broader view over time such as change in mobility as a result of a 3-month physical therapy program after acute care discharge. Still, other measures have a comprehensive and integrated view such as perceived quality of life. Measures can be at the patient, provider, organization, or system level and can be patient related, system related, practitioner or performance related, and cost/financial related.

Classification of Measures

Some common classes of measures include structural, process, outcome, disease specific, economic, and composite. Structural measures examine fixed aspects of health care delivery such as the physical plant and human resources of the facility, board certification of providers, availability of multidisciplinary team members, diagnostics testing, and interventions. Process measures address observable behaviors or actions that a provider undertakes to deliver care including both technical and interpersonal components. Examples are checking to see if a patient smokes and providing smoking cessation information to smokers. A process measure can be as simple as determining if an item in the process of care has or has not been completed. Process measures are useful for internal quality improvement efforts. Outcome measures represent health care delivery end points or results of care and are of interest to the provider and/or patient. They comprise both beneficial and adverse impacts on health care such as survival, complications, functional status, and both general and specific quality of life aspects. Outcomes are the most complex measures to collect and interpret. Improvement in outcomes is the focus of most clinical trials and evidence-based guidelines. Outcome measures are useful both for internal and external comparisons and improvement activities.

Disease-specific measures are available for a multitude of disease entities. For example, in measuring impact of specific disease processes for individual patients with back pain, the Oswestry Low Back Disability Questionnaire is useful. The Karnofsky Performance Status Measure is used to assess functional performance and independence in patients with cancer. The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) is specific for assessing neurological functional performance for stroke patients. There are also measures of overall quality of a disease-specific program. TJC has disease-specific care certification performance measurement programs for both heart failure and stroke.

The economics measures of health care are more complicated. Cost is the amount of resources used to produce or purchase an item or service. Charges are the amount of money an institution bills for an item or service. In health care, charges can be deceptive in that they are often discounted, making it difficult to arrive at the bottom line for health care services. There are three analyses frequently used to arrive at useful economic measures: cost–benefit analysis, cost-effectiveness analysis, and cost–utility analysis. Cost–benefit analysis is a type of analysis that compares the financial costs with the benefits of two or more health care treatments or programs. Health care interventions that have the same or better benefit at a lower cost are better values than treatments or programs that are more expensive. A cost–benefit analysis can help in identifying differences. Cost-effectiveness analysis (n.d.) is a type of analysis that is similar to a cost–benefit analysis but is applicable when the benefits cannot be measured in financial terms or dollars. For example, it is not possible to calculate a dollar value for an extra year of life (Cost-effectiveness analysis, n.d.). Measures such as quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) are used to measure impact on life. Cost–utility analysis is a comparison evaluation of two or more interventions in which costs are calculated in dollars and end points are calculated in quality of life units (Brosnan & Swint, 2012; Drummond, Sculpher, Torrance, O’Briend, & Stoddart, 2005). These economic analyses provide helpful information when making decisions about treatment options and expected value of care options including cost.

A new approach to examining cost of health care is Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing (TDABC), a model developed by Kaplan and Anderson (2007) for the business world, which is now being adapted to health care to improve quality and reduce costs. TDABC model requires estimates of only two parameters: (1) the unit cost of supplying capacity and (2) the time required to perform a transaction or an activity (Kaplan & Anderson, 2007). For example, in examining a patient health care encounter for an outpatient surgery, the patient can be followed from the time he or she enters the facility’s door until discharge. Following the patient every step of the way can be captured on a process map to which is added the time spent in each activity as well as what personnel interacted with the patient and any material resources used. The amount of time each provider spends with the patient can be used to calculate the cost of that service (e.g., salary/hour × amount of time spent). In addition, the cost of any materials or equipment used must be calculated. The process map can be easily assembled using a number of software packages. Once the process map and costs are assembled, the team of providers who provide the services and other stakeholders can analyze the map to identify inefficiencies and waste and reconfigure a new more efficient and cost-effective process map for implementation. By comparing calculated time and costs for the before and after process maps, improved efficiency and cost saving can be calculated. The TDABC approach offers a new model for improving the efficiency and quality of care from the perspective of patients and providers while reducing cost of care, a win-win scenario for all stakeholders.

Finally, composite measures of overall health-related quality of life (HRQL) are available. For example, the EuroQol and the Short Form 12-item Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-12) are generic measures that provide an overall assessment of multidimensional concepts such as HRQL. Other examples of composite multidimensional measures are patient satisfaction surveys such as the Press Ganey survey and measures of functional assessment such as the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) and the Barthel Index.

Value in Health Care

Michael Porter, a recognized leader for business management, has proposed transforming health care from one of cost control to one with a focus on value creation. He notes that achieving high value for patients must become the overarching goal of health care delivery. What is important to patients should be what is important to providers and become the mutual goal of all involved in the delivery of health care, thus supporting patient centeredness. Value is defined as the health outcomes achieved per dollar spent (Porter & Teisberg, 2006). Porter (2010) describes value as an equation in which outcome is the numerator (e.g., condition specific and multidimensional) and cost is the denominator (e.g., total costs of a full cycle of care for the patient’s medical condition).

In Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results (Porter & Teisberg, 2006), the authors summarize their observations about the current health system and their vision of an efficient, high-value system. According to Porter and Teisberg (2006), value in health care is a function of the health outcomes achieved and the health-related costs incurred over time for an individual. Value is not simply based on minimizing costs. Rather, it is based on maximizing outcomes and minimizing costs over time for persons with discrete health needs. The health outcomes realized by individuals are not dichotomous (alive or dead) but multidimensional. Health outcomes or health can be categorized into three major categories: health risk status, disease status, and functional health status (e.g., physical, mental, and social domains). The cost incurred by individuals or payers are not limited to a single event such as a surgical procedure, a hospitalization, or a clinic visit but rather include the costs of a full set of services used during a full “care cycle” for a particular health problem or condition (Nelson, Batalden, Godfrey, & Lazar, 2011).

Porter and Teisberg (2006) underscore the notion that value is created by frontline integrated practice units (e.g., interprofessional teams) who provide care to individuals with discrete health needs (e.g., cardiac disease, diabetes mellitus, colon cancer). To measure value, one must track key multidimensional outcomes of individuals and subpopulations with a given health condition during the care cycle while simultaneously tracking the dollars expended by or on behalf of those individuals. The current U.S. payment systems do not reward high-value providers. Thus, their major recommendation for the transformation of the health care system is to build an environment for value-based competition in health care. Because value is in the eyes of the beholder, the work of measuring value is challenging but making progress as the science of quality improvement and measurement mature.

Porter and Teisberg (2006) underscore the notion that value is created by frontline integrated practice units (e.g., interprofessional teams) who provide care to individuals with discrete health needs (e.g., cardiac disease, diabetes mellitus, colon cancer). To measure value, one must track key multidimensional outcomes of individuals and subpopulations with a given health condition during the care cycle while simultaneously tracking the dollars expended by or on behalf of those individuals. The current U.S. payment systems do not reward high-value providers. Thus, their major recommendation for the transformation of the health care system is to build an environment for value-based competition in health care. Because value is in the eyes of the beholder, the work of measuring value is challenging but making progress as the science of quality improvement and measurement mature.

MEASUREMENT

MEASUREMENT

Measurement is important because it drives quality improvement; informs providers, consumers, and policy makers; and influences payment (NQF, n.d.-b). According to the NQF, measures are the only way one can really know if care is safe, efficient, effective, and patient-centered. An often used cliché about measurement is, “if you can’t count (measure) it, you can’t control it.” Therefore, the possibility of improving outcomes is based on valid and reliable measurement techniques and data. Because many aspects of health care can be measured, how do we choose what to measure, and how do we identify the most appropriate tool for measuring the desired phenomenon? The answer to what to measure depends on what is considered the critical elements or indicators that influence quality outcomes. National organizations such as AHRQ, NQF, and TJC have created portfolios of evidence-based measures for multiple health care conditions and settings (Box 12-1). Other organizations have created disease-specific measures. Choosing the right tool is the second step for consideration. One searches for the most appropriate valid and reliable measure to collect the desired information. For example, to measure blood pressure, a thermometer would be useless. However, a thermometer is appropriate for measuring temperature.

Box 12-1 National Quality Forum

National Quality Forum (NQF) is a not-for-profit, nonpartisan, membership-based organization that works to catalyze improvements in health care. The NQF endorsement is considered a gold standard for health care quality. NQF-endorsed measures are evidence-based and valid and in tandem with the delivery of care and payment reform. NQF has a portfolio of endorsed performance measures that can be used to measure and quantify health care processes, outcomes, patient perceptions, and organizational structure and/or systems associated with high-quality care. Once a measure is endorsed by NQF, it can be used by hospitals, health care systems, and government agencies such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for public reporting and quality improvement (NQF, n.d.-a). In fact, CMS use of NQF measures is tied to reimbursement for services.

Characteristics of Measures and Indicators

In choosing any measure, indicator, or tool, there are several attributes important for consideration. These attributes include that the measure/indicator is (1) based on a clear operational definition, (2) specific and sensitive to the phenomenon of interest, (3) valid and reliable, (4) one that discriminates well, (5) related to the clearly identifiable interest of the user (e.g., if meant for the provider, it is relevant to providers’ practice), (6) one that permits useful comparison, and (7) evidence-based. Each measure/indicator must be clearly defined and must provide sufficient data specifications so that it can be accurately collected, analyzed, and interpreted for the intended purpose (Mainz, 2003a, 2003b).

The basic principles of measurement include addressing validity, reliability, and bias. Validity is the degree to which the indicator measures what it is intended to measure (i.e., the indicator accurately captures the true state of the phenomenon being measured). As applied to health care quality, a valid indicator discriminates between care that meets accepted standards and care that does not. The indicator also concurs with other measures designed to measure the same dimension of quality (Mainz, 2003a). Reliability is the extent to which repeated measurements of a stable phenomenon by different data collectors, judges, or instruments, at different times and places, provide similar results. In order to make comparisons among or within groups or populations over time, the characteristic of reproducibility and consistency are critical characteristic of reliability (Mainz, 2003a). There can be variations in validity and reliability of indicators, so the user must be aware of these factors. Bias is another consideration in use of measures/indicators. Bias is any factor, recognized or not, that distorts the findings of a study. In research studies, bias can influence the observations, results, and conclusions of the study and make results less accurate, thus threatening validity and reliability (Cost-effectiveness analysis, n.d.). For example, the origin of the bias can come from selection of patients for inclusion, the evaluator, data collection process, analytic techniques, or interpretation of results. It is clear from this brief discussion that the selection of quality measures/indicators is critical for addressing quality and outcomes in health care.

Comparing Measures and Outcomes

Information gathered from the use of measures and indicators is important to inform quality improvement work for both internal and external comparisons and benchmarking. A benchmark in health care refers to an attribute or achievement that serves as a standard; it may be used for other providers or institutions to emulate. Benchmarks differ from other standard care goals in that benchmarks are derived from empirical data (e.g., performance or outcomes data). For example, a statewide survey might produce risk-adjusted 30-day rates for death or other major adverse outcomes from stroke. After adjusting for relevant clinical factors, the top 10% performer hospitals can be identified based on particular outcome measures. These institutions would then provide benchmark data about these outcomes (Patient safety, n.d.). Maintaining a robust database or registry is the basis for benchmarking. Benchmarking individual results to high-performance outcomes help individuals and groups (teams) to gain a realistic picture about their current performance and gaps in quality, and it helps them to set targets for the future. Performance data are being reported using mechanisms such as scorecards, dashboards, and report cards to provide a visual snapshot of achievement on specific outcomes. These formats of comprehensive information can be the basis for informed decision making about current and future goals for practice and care. It also provides information for program evaluation.

INTERPROFESSIONAL TEAMS

INTERPROFESSIONAL TEAMS

What is the relevance of quality, measurement, and outcomes for the interprofessional health care team? Quality, and its inherent component of safety, is a national priority for a transformed health care system. Quality is multidimensional, and those dimensions can be measured using a variety of measures and indicators which can discriminate between best evidence-based practices and outcomes and those that are not. In order to provide the best care, thus high-quality care, interprofessional teams must integrate responsibility and accountability for outcomes management into the work of delivering care. Ellwood (1988), considered the founder of outcomes management, defined outcomes management as “a technology of patient experience designed to help patients, payers, and providers make rational medical care–related choices based on better insight into the effect of these choices on the patient’s life.” Further, he notes that this technology “consists of a common patient-understood language of health outcomes; a national database containing information and analysis on clinical, financial, and health outcomes that estimates, as best we can, the relation between medical interventions and health outcomes, as well as the relation between health outcomes and money; and an opportunity for each decision-maker to have access to the analyses that are relevant to the choices they must make.” (Ellwood, 1988, p. ) This description sets a framework for the work of all members of the interprofessional team and includes the following: (1) commitment, as an individual and as a team, to the mutual goal of ongoing quality management and improvement and accept responsibility and accountability for outcomes; (2) knowledge of what the key evidence-based measures or quality indicators are related to your patient population and practice; (3) understanding of how data are collected, recorded, and analyzed to appreciate the influence of validity, reliability, and bias; (4) monitoring key selected outcomes on a regular basis and over time to see trends; (5) presentation of the data in a concise format such as a scorecard for all stakeholders to easily see and understand; (6) basing of practice and care decisions on data; and (7) benchmarking with national organizations to gauge your performance. Ongoing attention to quality improvement and decreasing the cost of care are critical to transforming the current health care system into one that is value driven and patient-centered.

What is the relevance of quality, measurement, and outcomes for the interprofessional health care team? Quality, and its inherent component of safety, is a national priority for a transformed health care system. Quality is multidimensional, and those dimensions can be measured using a variety of measures and indicators which can discriminate between best evidence-based practices and outcomes and those that are not. In order to provide the best care, thus high-quality care, interprofessional teams must integrate responsibility and accountability for outcomes management into the work of delivering care. Ellwood (1988), considered the founder of outcomes management, defined outcomes management as “a technology of patient experience designed to help patients, payers, and providers make rational medical care–related choices based on better insight into the effect of these choices on the patient’s life.” Further, he notes that this technology “consists of a common patient-understood language of health outcomes; a national database containing information and analysis on clinical, financial, and health outcomes that estimates, as best we can, the relation between medical interventions and health outcomes, as well as the relation between health outcomes and money; and an opportunity for each decision-maker to have access to the analyses that are relevant to the choices they must make.” (Ellwood, 1988, p. ) This description sets a framework for the work of all members of the interprofessional team and includes the following: (1) commitment, as an individual and as a team, to the mutual goal of ongoing quality management and improvement and accept responsibility and accountability for outcomes; (2) knowledge of what the key evidence-based measures or quality indicators are related to your patient population and practice; (3) understanding of how data are collected, recorded, and analyzed to appreciate the influence of validity, reliability, and bias; (4) monitoring key selected outcomes on a regular basis and over time to see trends; (5) presentation of the data in a concise format such as a scorecard for all stakeholders to easily see and understand; (6) basing of practice and care decisions on data; and (7) benchmarking with national organizations to gauge your performance. Ongoing attention to quality improvement and decreasing the cost of care are critical to transforming the current health care system into one that is value driven and patient-centered.

QUALITY AND OUTCOMES SPECIFIC TO STROKE

QUALITY AND OUTCOMES SPECIFIC TO STROKE

Part one of this chapter has addressed quality measures, indicators, outcomes, and measurement in health care as foundational information for discussion specific to stroke care and stroke programs. Part two addresses the role of quality and outcome measurement in a hospital or program focused on the care of patients with stroke. Stroke quality and outcome measurement has evolved over the past decade, as the greater health care system has turned its attention to improving care and measuring the outcome of care. The development of stroke program quality measures and outcome assessment is rooted in the development of stroke systems of care through third-party certification. External certification-guided stroke program performance improvement and measurement of outcomes has evolved to a large extent since 2003. Stroke quality and outcome measurement has also been influenced by the ongoing development of national quality programs through the CMS, commonly called core measures. Therefore, this section will first provide an overview of the development of national stroke quality measures influenced by TJC and CMS. Finally, current controversies complicating the measurement of stroke care quality and reporting will also be discussed.

Quality and Outcomes in Stroke Programs

Certification Standards

Disease-specific certification (DSC) is a voluntary third-party certification of a program of care within an accredited hospital. Although TJC is not the only organization providing external disease program certification, they were the first to do so and remain the largest organization in the country offering this service (TJC, 2014). The TJC also has a formal relationship with American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) and develops and revises certification requirements in conjunction with thought leaders from the AHA/ASA. Therefore, the certification remains influential nationally and is guiding the development of a stroke system of care in the United States.

The DSC certification requirements consist of a set of standards and performance measures. The first DSC certification program was offered by TJC for stroke programs in 2003, and stroke certification continues to be the largest DSC program for the organization (TJC, 2003, 2014). The DSC standards and metrics provide a health care program management infrastructure for all programs, regardless of the disease process reviewed. The standards are written with the framework of Donabedian’s health care model of structure, process, and outcome. The standards, coupled with the TJC published performance metrics (a separate document), address all three areas of health care program evaluation. Many standards are general and apply to all programs regardless of the disease population managed. Standards are minimum criteria within the program that must be met. Some standards are then expanded to include elements specific to the disease managed. For example, all DSC programs must have a performance improvement program where staff monitors quality within the program and intervenes when quality or processes are compromised. Additional specificity is then provided to stroke programs by stating certain elements of the program must be monitored, such as the process and outcomes of intravenous fibrinolysis for ischemic stroke and endovascular therapies.

For stroke program certification, TJC standards are developed in conjunction with the AHA/ASA’s technical advisory panel. The technical advisory panel is composed of a physician, a nurse, and other interprofessional leaders in the stroke field who provide input into TJC standards  . The TJC DSC standards are revised to reflect current practice and national clinical practice guidelines every 18 to 24 months. The standards have included a performance measurement chapter since the inception of the program, establishing program quality monitoring and outcome measurement as a hallmark of certified stroke programs. With each revision, performance measurement has remained a central focus of program certification. Current standards state a program must have the following:

. The TJC DSC standards are revised to reflect current practice and national clinical practice guidelines every 18 to 24 months. The standards have included a performance measurement chapter since the inception of the program, establishing program quality monitoring and outcome measurement as a hallmark of certified stroke programs. With each revision, performance measurement has remained a central focus of program certification. Current standards state a program must have the following:

● An organized, comprehensive approach to performance improvement

● Develop a performance improvement plan

● Trend and compare data to evaluate processes and outcomes

● Use information garnered from measurement data to improve or validate clinical practice

● Use patient-specific, care-related data

● Evaluate the patient’s perception of the quality of care

● Maintain data quality and integrity (TJC, 2014)

This attention to performance measurement and improvement in the DSC standards cemented quality and outcome measurement as a cornerstone of hospital-based stroke program over the past decade.

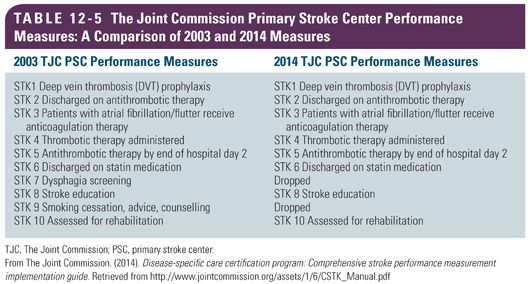

Certification Performance Measures

The TJC also maintains DSC performance measures in addition to minimum program standards. The performance measurements analyze either processes of care or patient outcome, whereas program standards generally address the structure of care delivered. Similar to the process for standard development, performance metrics are developed in conjunction with the AHA/ASA and reviewed every 18 to 24 months. The performance measures have evolved over the years, as clinical practice has changed based on evidence and as the technical advisory panel evaluated the metrics. With the initial stroke DSC certification in 2003, 10 performance measures were launched (Table 12-5) (TJC, 2008). The initial measures were all assessments of process of care, evaluating the initial emergency room treatment of the patient with ischemic stroke and the in-hospital treatment of patients with transient ischemic attack (TIA), ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), and subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Although the definitions of the numerators and denominators changed over the years between 2003 and 2009, the measures remained relatively constant. Until the late 2000s, only hospitals pursuing stroke certification were required to monitor these measures and certified centers had to report their performance to TJC. However, public reporting was not required. This changed in 2009 when the TJC stroke measures were evaluated by CMS and the NQF and became a part of the CMS Inpatient Quality Reporting program, commonly called core measures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree