Infective Endocarditis

Carlos A. Roldan

Infective endocarditis (IE) is associated with significant morbidity and mortality if not promptly recognized and treated.

General and cardiovascular symptomatology associated with IE is frequently nonspecific.

The most common clinical manifestations of IE (fever and heart murmurs) are nonspecific.

Heart murmurs are frequently not audible in patients with IE with mild to moderate valve regurgitation.

Peripheral manifestations of IE, such as Osler nodes and Janeway lesions, are uncommon.

Integration of clinical and echocardiography (echo) data, therefore, is critical for the diagnosis, risk stratification, and management of IE.

Definition

Native IE is an infection of the endothelial lining of the heart valves, mitral or tricuspid chordae tendineae, valve annulus, aortic root, and infrequently of the endocardium or myocardium.

Prosthetic IE is an infection of the bioprosthetic or mechanical leaflets, valve struts, sewing or annuloplasty rings, and contiguous mitral or tricuspid chordae tendineae, aortic root, and infrequently of the endocardium or myocardium.

IE is typically characterized by fever and a heart murmur, positive blood cultures, and confirmed by echo or pathologic evidence of valvular or paravalvular infection.

Pre-Existent Heart Diseases

Pre-existing heart disease is found in at least two-thirds of cases of left-sided IE (Table 13.1).

Pre-existing heart disease is uncommon in right-sided IE.

In patients ≤40 years old, rheumatic heart disease (in developing countries) and mitral valve prolapse or intravenous drug abuse (in developed countries) are the most common predisposing causes.

In patients ≥60 years old, aortic valve sclerosis or stenosis and mitral annular sclerosis with mild or worse regurgitation, prosthetic heart valves, and pacemaker or defibrillators are the most common underlying cardiac pathologies or substrates.

In either age group, at least one-third of patients have normal valves or clinically unrecognized valve disease.

Distribution of Types of Infective Endocarditis

Subacute and acute IE of native left heart valves constitute 60% to 75% and 5% to 10% of all cases, respectively:

Isolated aortic valve IE is observed in 55% to 60% of cases.

Isolated mitral valve IE occurs in 25% to 30% of cases.

IE of both valves occurs in about 15% of cases.

Prosthetic valve IE constitutes 10% to 25% of all cases of IE:

Prosthetic valve IE is more common with prosthetic aortic valves, multiple valves, and after replacement of an infected native valve.

Right-sided IE, most commonly associated with intravenous drug abuse and uncommonly with right heart wires or catheters, constitutes 5% to 10% of all cases:

The tricuspid valve is predominantly involved (80% of cases).

Culture-negative IE constitutes 5% to 10% of all cases of IE.

Most Common Pathogens

Acute native IE: Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae or pyogenes, Haemophilus influenzae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and beta-hemolytic streptococci.

Table 13.1 Predisposing heart diseases for infective endocarditis

Condition

15–60 y (%)

>60 y (%)

Rheumatic heart disease

25–30

8

Mitral valve prolapse

10–30

10

Intravenous drug abuse

15–35

10

Congenital heart disease

10–20

2

Degenerative heart disease

Rare

30

Other

10–15

10

None

25–45

25–40

Subacute native IE: Streptococcus viridans and Staphylococcus aureus.

Early prosthetic valve IE: Staphylococcus epidermidis.

Late prosthetic valve IE: Streptococcus viridans and Staphylococcus aureus.

Right-sided native IE: Staphylococcus aureus in most cases followed by streptococci, enterococci, gram-negative bacteria, and fungi.

Acute right-sided IE related to pacemaker or automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator wires: Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis.

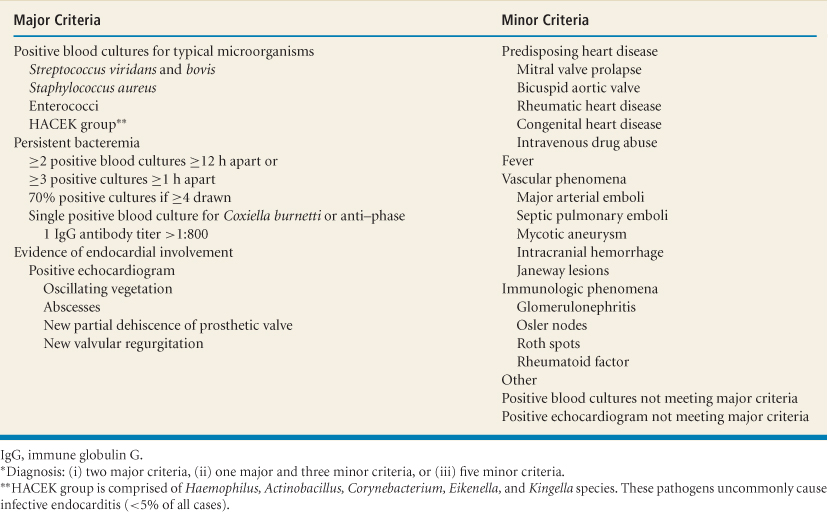

Table 13.2 Duke diagnostic criteria for infective endocarditis*

Chronic right-sided IE related to pacemaker or automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator wires: Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, and gram-negative bacteria.

Culture negative IE: In most cases (60%) due to antibiotic therapy before blood cultures and then by Candida, Aspergillus, or slow-growing microorganism (Coxiella burnetti, Bartonella).

Diagnosis

Definite Diagnosis

Microorganisms demonstrated by culture or histology in a vegetation or histologic evidence of active vegetation or an intracardiac abscess.

Definite Clinical Diagnosis

Duke criteria: Two major criteria, one major and three minor criteria, or five minor criteria (1,2) (Table 13.2):

Other uncommon minor criteria (clubbing, splenomegaly, splinter hemorrhages, petechiae, central nonfeeding venous lines, peripheral venous

lines, microscopic hematuria, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate [>30 or >50 mm/hour for patients younger than or older than 60 years, respectively] and C-reactive protein) increase the sensitivity and maintain high specificity of the Duke criteria for diagnosis of native and prosthetic valve IE.

Possible Infective Endocarditis

One major criterion and one minor criterion; or three minor criteria.

Rejected Infective Endocarditis

If an alternate diagnosis explains manifestations suggestive of IE.

If clinical manifestations or pathologic evidence of IE were not found after ≤4 days of antibiotics.

Echocardiography

Class I or Appropriate Indications for Use in Infective Endocarditis

Transthoracic echo (TTE) and especially transesophageal echo (TEE) are highly accurate and cost-effective for the diagnosis, risk stratification, and guiding of therapy of IE (1,2,3,4,5) (Table 13.3).

In a patient with a suggestive clinical syndrome, echo confirms the diagnosis of IE by the detection of vegetations (the sine qua non of this condition) or its associated complications.

In a patient with high pretest likelihood of IE, absence of vegetations on echo does not exclude IE, but it makes the diagnosis unlikely or defines a benign prognosis (6).

In patients with low likelihood of IE, echo has limited additive diagnostic and prognostic value.

In patients with intermediate likelihood of IE, echo and especially TEE play the most important diagnostic and prognostic role.

Large (>10-mm) or multiple vegetations, severe valve dysfunction (moderate to severe regurgitation), abscesses, leaflet perforation, aneurysms or pseudoaneurysms, fistula, ring dehiscence, multivalvular involvement, cerebroembolism, and prosthetic valve infection predicts high morbidity and mortality and frequently indicate the need for valve surgery (7).

Echo can also define the mechanism of valve regurgitation and the hemodynamic impact of regurgitant lesions on size and function of the left ventricle (LV), size of the left atrium (LA), and LA and pulmonary artery pressures.

Although the diagnosis of IE can be made by clinical and microbiology data alone, the diagnosis of IE still relies on the demonstration of endocardial disease by echo.

Table 13.3 Class I or appropriate (score 7–9) indications for echocardiography in infective endocarditis of native and prosthetic valves*

Initial evaluation of suspected native or prosthetic valve infective endocarditis, especially if positive blood cultures or a new murmur.

Detection and characterization of valvular lesions, their hemodynamic severity, and ventricular compensation.**

Detection of vegetations and characterization of lesions in patients with congenital heart disease.

Detection and characterization of abscesses, perforation, fistulas, aneurysms, or pseudoaneurysms.**

Re-evaluation studies in patients with high risk or complex endocarditis (virulent organism, new murmur, severe hemodynamic lesion, aortic valve involvement, persistent or recurrent fever or bacteremia, clinical change or symptomatic deterioration).

Patients with highly suspected culture-negative infective endocarditis.**

Evaluation of bacteremia without a known source in a patient with a prosthetic valve.**

*All of these indications are based on Level of Evidence B or C.

**Transesophageal echocardiography may provide incremental value in addition to information obtained by transthoracic echocardiography.

M-Mode, Two- and Three-dimensional Transthoracic and Transesophageal Echocardiography: Valve Morphology

Best Imaging Planes

A systematic approach to the performance and interpretation of TTE and TEE in a patient with suspected IE is essential to the diagnostic accuracy of echo.

Careful scanning of one heart valve at a time should be performed in multiple planes at short depth settings (12 cm for TTE and 4 to 8 cm for TEE) and with a narrow sector scan to improve image resolution.

By TEE, for each valve and especially from the midesophageal views, 2D and RT3D images followed by color Doppler imaging should be performed at different valve and subvalvular levels by slowly advancing or withdrawing the probe.

In our laboratory, the following sequence of TEE interrogation of all heart valves are used:

Transgastric four-chamber and transgastric short- and long-axis views of the mitral and tricuspid valves. These views of the tricuspid valve allow the best assessment of the posterior leaflet.

Transgastric short-axis view of the mitral valve as the TEE probe is withdrawn from the transgastric to the midesophageal level.

Midesophageal four- and two-chamber views, with a sector scan limited to the mitral or tricuspid valve and scanning of the valves at multiple planes and levels. These are the best views for RT3D TEE full-volume and zoom imaging of the mitral and tricuspid valves.

Midesophageal short-axis view with multiplane interrogation is the best view for 2D and RT3D imaging of the aortic and then of the pulmonic valve.

In addition to characterizing valve vegetations and associated complications, valve and subvalvular apparatus are assessed for thickening, hyperreflectance, calcification, retraction, and mobility. These characteristics help to categorize a valve morphology as myxomatous, degenerative, rheumatic, or congenital.

The presence and severity of valve regurgitation is defined according to established color Doppler echo criteria described in other chapters of this book.

RT3D TEE has equal to higher sensitivity and specificity than 2D TEE for the detection of valve vegetations (9,10).

Key Diagnostic Features of Specific Abnormalities

Valve Vegetations

Vegetations are the sine qua non and most common abnormality of IE.

Vegetations are distinctive masses attached most commonly to the leaflets and characterized by their location, size, shape, echoreflectance, and mobility.

Location

Vegetations are most commonly located at the leaflet coaptation point on the atrial side of atrioventricular valves and ventricular side of semilunar valves (Figs. 13.1 and 13.2).

Uncommon locations for valve vegetations include the aortic-mitral intervalvular fibrosa (Fig. 13.3), aortic or mitral annulus, intracavitary endocardium, and the ventricular side of the mid- to distal portions of the anterior mitral leaflet or chordae tendineae as a result of an aortic regurgitation jet lesion in aortic valve endocarditis or from a contact lesion with the basal septum in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyo-pathy.

Also in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, vegetations can be rarely seen on the basal septum as a result of a contact lesion with the mitral valve.

Size

Vegetations are of variable size, but usually >3 mm. A vegetation is small if it measures <5 mm in diameter, of moderate size if it measures 5 to 10 mm, and large if measures >10 mm (Figs. 13.1 through 13.4).

Shape

Echoreflectance

Echoreflectance of recent vegetations is that of the myocardium (homogeneous soft tissue echoreflectance) and, less frequently, of heterogeneous appearance.

Infrequently, recent and large vegetations can have discrete areas of echolucency that suggest an in situ abscess formation (Fig. 13.4).

Vegetations denser than the myocardium or partially or completely calcified denote chronicity and are likely healed lesions.

Mobility

A pedunculated, elongated, or prolapsing mass has a characteristic independent rotatory mobility.

Uncommon sessile lesions move with the underlying leaflet.

Detection of Complications

Valve Perforation

The aortic right and left coronary cusps (Figs. 13.5 through 13.7), the aortic-mitral junction or intervalvular fibrosa, and basal to midportions of the anterior or posterior mitral leaflet (Fig. 13.8) are the sites most commonly involved (9,10,11,12).

Perforation of the aortic-mitral intervalvular fibrosa or anterior mitral leaflet can result from ulceration with or without a preceding pseudoaneurysm formation by a metastatic infection from a regurgitant aortic valve (a jet lesion) (13,14).

A perforation can occur on any leaflet portion but more commonly occurs in the area adjacent to vegetations or leaflet thickening.

A perforation appears as a leaflet tissue discontinuity of variable size.

Demonstration by color Doppler of a jet through a leaflet discontinuity highly supports the diagnosis.

Up to 50% of leaflet perforations, especially those of the mitral valve, are associated with or preceded by a pseudoaneurysm or aneurysm.

Valvular, Annular, Aortic Root, or Myocardial Abscesses

Abscesses occur in 20% to 40% of cases of IE and are twice as common with prosthetic valves.

Abscesses are predominant in the aortic posterior annulus or posterior aortic root (Fig. 13.9

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree